Franks and Holy RomansClick on links or small images below to see larger images for Unit 6

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0601CoronCharlemagne.jpg

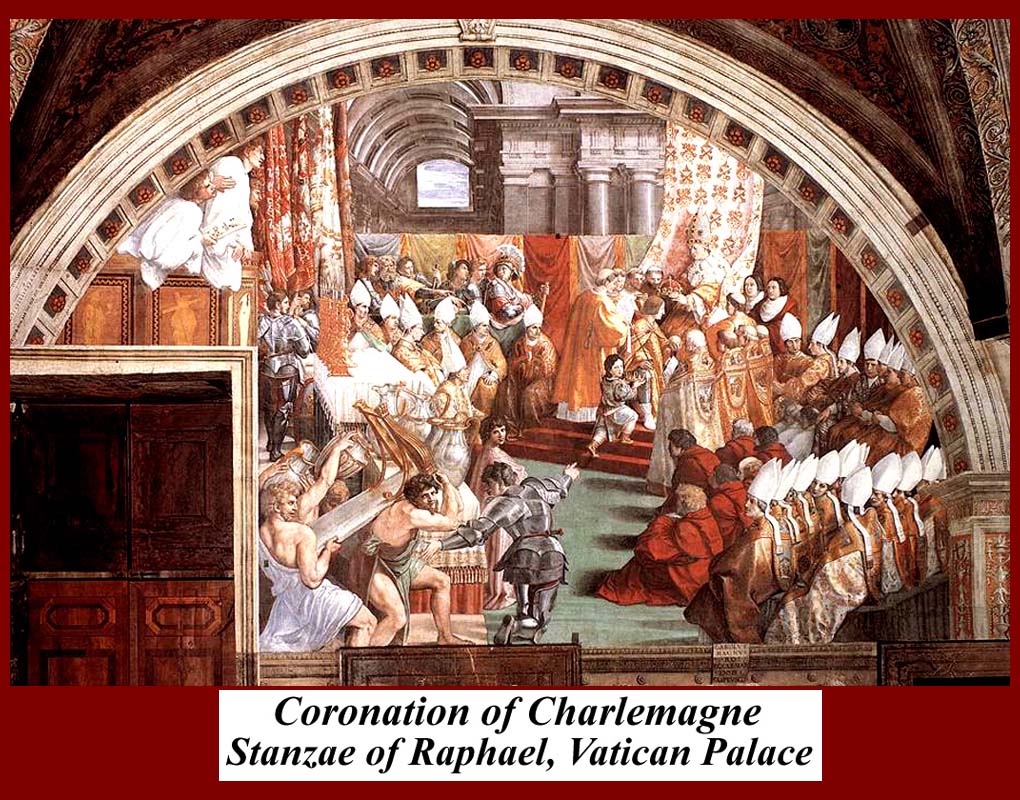

The coronation of Charlemagne on the evening of Christmas Day, 800 AD, by Pope Leo III was the high point of a diplomatic dance that had begun years before between the Pope and Pepin the Short. This unit will investigate what led up to that coronation and the relationship between Charlemagne and his successors, the Holy Roman Emperors, on the one hand and the papacy on the other.

For more information on the Coronation and on Charlemagne, see

http://pirate.shu.edu/~wisterro/cdi/0800a_coronation_of_charlemagne.htm and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlemagne or

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03610c.htm

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0602Clovis.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0602xClovis.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0603Merovingians.jpg

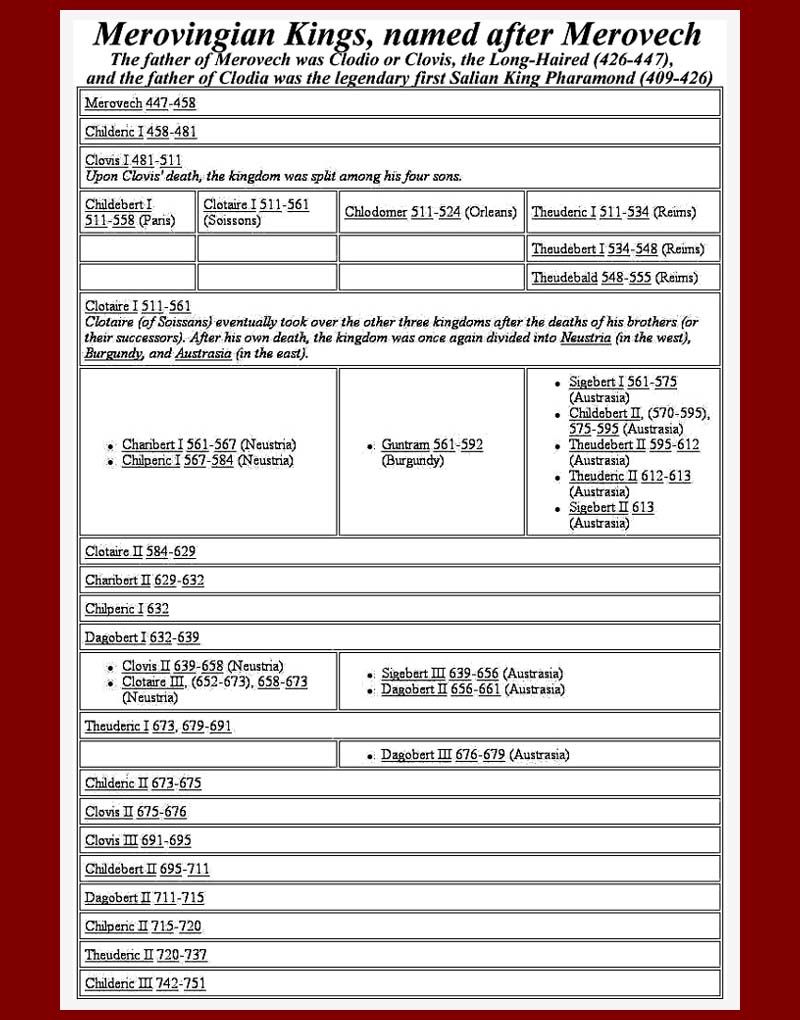

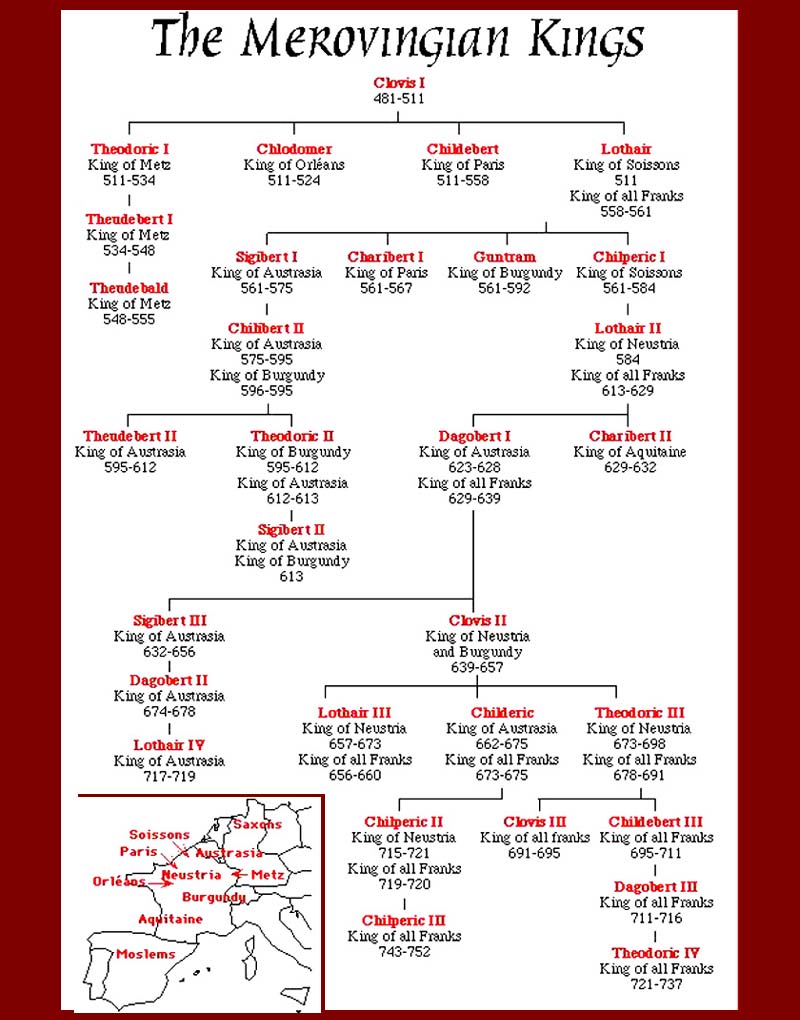

The Franks (Latin: Franci < pronounced frahn-kee > or gens Francorum) were a West Germanic tribal confederation first mentioned in Roman history in the third century as living north and east of the Lower Rhine River. From the third to fifth centuries AD some Franks raided Roman territory while other Franks joined the Roman armies in Gaul as auxiliaries. As was normal for the times, the Frankish foederati relationship with Rome was fluid -- different Frankish groups might move from one side of the battle lines to the other according to circumstances. Only the Salian Franks formed a kingdom on Roman-held soil that was acknowledged by the Romans after AD 357.

In the climate of the collapse of imperial authority in the West, the Frankish tribes were united under the (Salian) Merovingians and conquered all of Gaul except Septimania (southern France along the Mediterranean, east of Provence -- map) in the 6th century. The Salian political elite would be one of the most active forces in spreading Christianity over western Europe.

The Merovingian dynasty, descended from the Salians, founded one of the Germanic monarchies which replaced the Western Roman Empire from the fifth century. It is impossible to determine to what extent different Western European groups described or referred to themselves as the Franks. The cultural and linguistic descendants of the Franks, the modern Dutch-speakers of the Netherlands and Flanders, seem to have broken with this endonym around the 9th century as Frankish identity had gradually changed from an ethnic identity to a national identity and was now mostly used by, and referring to, Old Gallo-Romance-speaking inhabitants of the Frankish Empire; the future French.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0603xMerovech.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0604MerovingianStema.jpg

Clovis I (c. 466–511) was the first of the Merovingian kings of the large Frankish state, i.e., uniting all the Frankish tribes, but the Merovingian dynasty was named after his grandfather, Merovech, who had been the Frankish tribal leader who had joined with the Roman General Aetius and the Goth King Theodoric to defeat Atilla at the battle of the Catalunian Plains (Chalons) and who had been the first Frankish leader to seize Paris and make it his capital.

The politics of the Merovingians involved frequent civil warfare among branches of the family. During the final century of the Merovingian rule, the dynasty was increasingly pushed into a ceremonial role -- the Merovingians became lazy and effete and their military courtiers took advantage by accruing power to themselves.. The Merovingian rule was ended March 752 when Pope Zachary formally deposed Childeric III.

The name Clovis appears to have been a Latinization of the Germanic name Khlodovech. The French and English names spelled Louis (but pronounced differently, of course) and the German name Ludwig are from the same source.

For more information, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franks and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salian_Franks and

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0604MerovingianStema.jpg.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0605MartelPepin.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0605wCoronationPepin.jpg

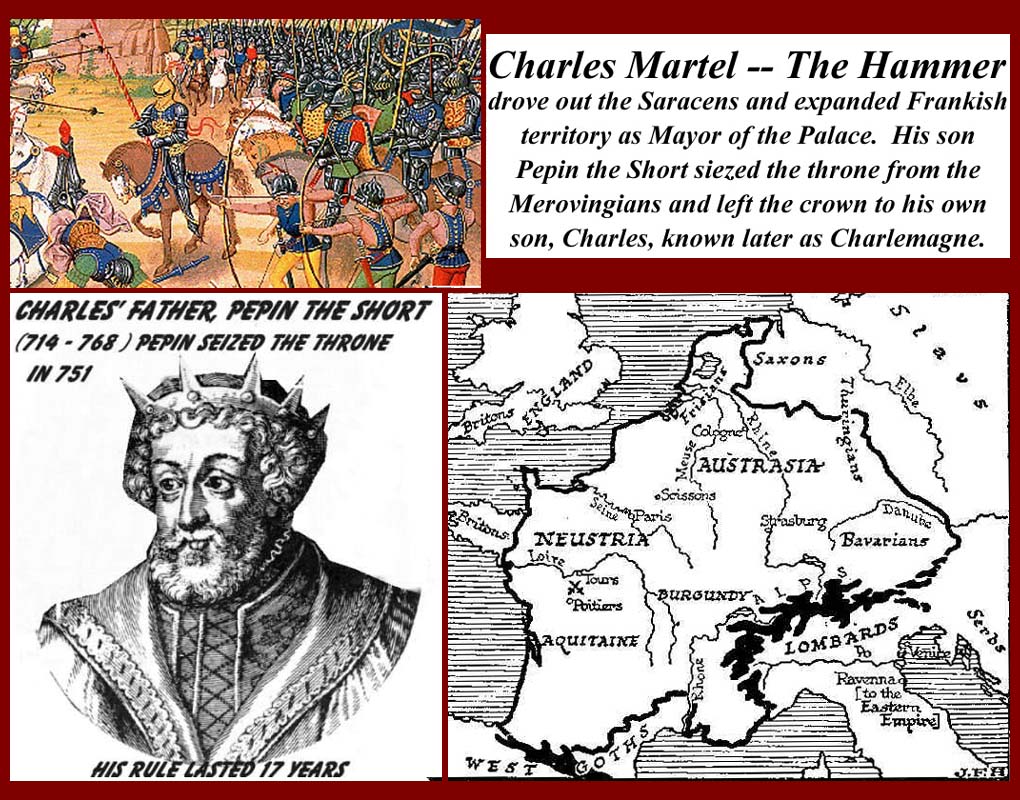

Charles Martel (Latin: Carolus Martellus) (ca. 688 – 22 October 741), literally "Charles the Hammer", was a Frankish military and political leader, who served as Mayor of the Palace under the Merovingian kings and ruled de facto during an interregnum (737–43) at the end of his life, using the title Duke and Prince of the Franks. In 739 he was offered the title of Consul by the Pope, but he refused. He is remembered for winning the Battle of Tours in 732, in which he defeated an invading Muslim army and halted northward Islamic expansion in western Europe.

A brilliant general, he lost only one battle in his career (the Battle of Cologne). He is a founding figure of the Middle Ages, often credited with a seminal role in the development of feudalism and knighthood, and laying the groundwork for the Carolingian Empire. He was the father of Pepin and the grandfather of Charlemagne.

Pepin (714 – 24 September 768), called le Bref ("the Short"), also known as Pepin the Younger or Pepin III, was the Mayor of the Palace and dux et princeps Francorum (Duke of the Franks, a title originated by his grandfather and namesake Pepin of Heristal) from 741, and King of the Franks from 752 to 768. He was the father of Charlemagne.

When Charles Martel died in 741, Pepin and his brother Carloman had been declared "mayors" of the Franks. At this, their half-brother Grifo rebelled, leading several unsuccessful revolts, getting imprisoned and ultimately losing his life en route to joining the Lombards, enemies of the Franks. In 747, the pious Carloman decided to enter a monastery and left Pepin as the sole ruler of the Franks. Pepin decided that, since he already held the responsibilities of rule, he should also hold the title and the perquisites that went with it. He wrote to the pope with concerns about the powerless Merovingian figurehead. Pope Zacharias wrote back authorizing Pepin's coronation. The last Merovingian king, Childeric III, was deposed and sent to a monastery, and the "Mayor of the Palace" was crowned king at Soissons by St. Boniface acting as Apostolic Legate in November, 751.

For information on Charles Martell, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Martel and

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03629a.htm and

http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/army/p/martel.htm (Battle of Tours).

For information on Pepin, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pepin_the_Short and

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11662b.htm

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0605xDonationPepin.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0605yConstatineDonation1.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0605zConstatineDonation2.jpg

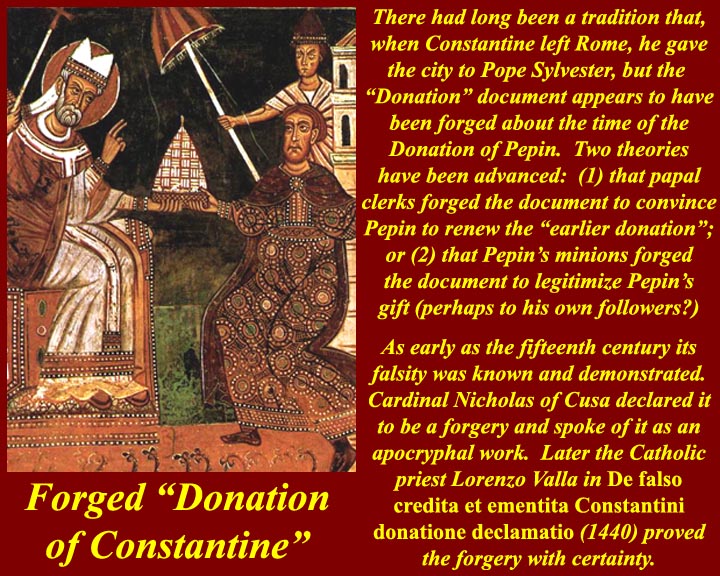

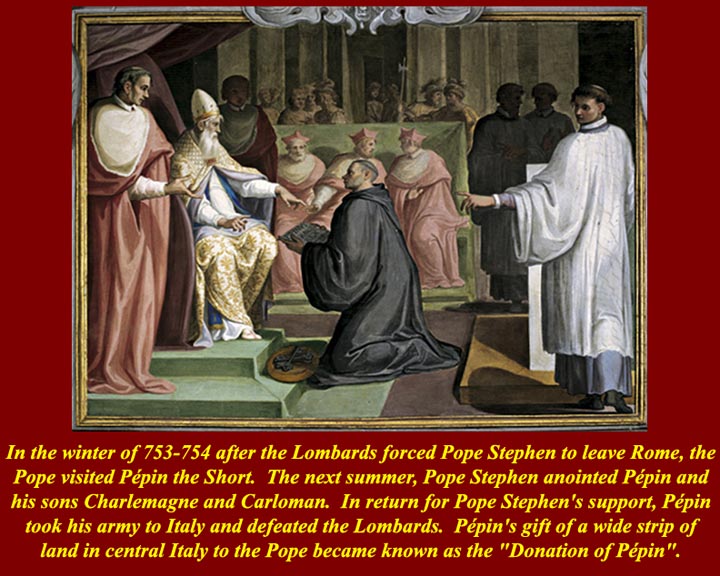

In the winter of 753-54, after the Lombards evicted Pope Stephen from Rome, Stephen visited Pepin the Short. The next summer, the Pope anointed Pepin and his sons Charlemagne and Carloman. In return for Stephen's support for his kingship of the Franks, Pepin took a Frankish army into Italy and defeated the Lombards. Pepin then turned a wide strip of conquered Italian territory over to the Pope. Those lands formed the basis for the Papal states and the gift became known as the Donation of Pepin. Pepin later expanded his Donation, and his son Charlemagne reiterated the Donation and expanded it again in the Donation of Charlemagne. (See http://www.traditioninaction.org/History/A_015_DonationCharlemagne.htm.)

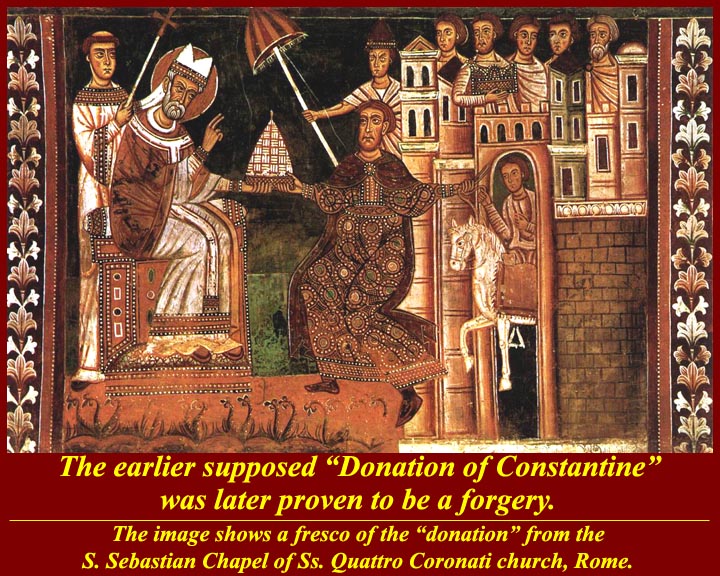

It was at about this time, either to encourage the Carolingian Donations or to add weight to them after the fact them, that the fraudulent Donation of Constantine was cooked up. In 1439, Lorenzo Valla demonstrated that the supposed Donation of Constantine as a forgery. His patron Alfonse V of Aragon (who was king of Naples) had been involved in land disputes with the Papal States then under Pope Eugene IV. The ultimate basis for the Papal claim was the Donation, which purported to be a specific grant of land rights and of ecclesiastical authority to the Roman Pope Sylvester (reigned 314-335) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. Valla was later brought into the Papal service. He was welcomed in Rome by the new pope, Nicholas V (Parentucelli), who made him an Apostolic Secretary, and this entrance of Valla into the Roman Curia has been called "the triumph of humanism over orthodoxy and tradition." Valla also enjoyed the favor of Pope Calixtus III (Alfonso de Borja). He achieved such high respect that he was buried in the church of St John Lateran.

See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorenzo_Valla and

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15257a.htm and

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/donatconst.html.

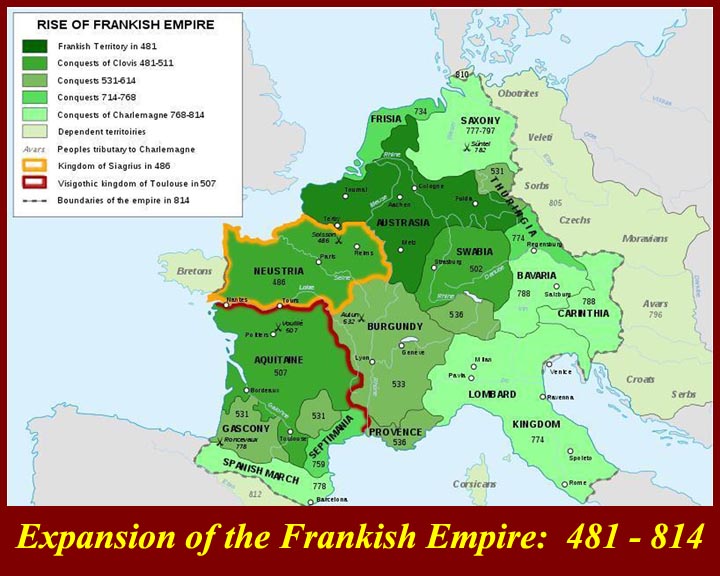

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0606aFrankishExpansion.jpg

The map shows the expansion of Frankish Territory under Pepin and Charlemagne.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0606bCharlemagneReliquary.jpg

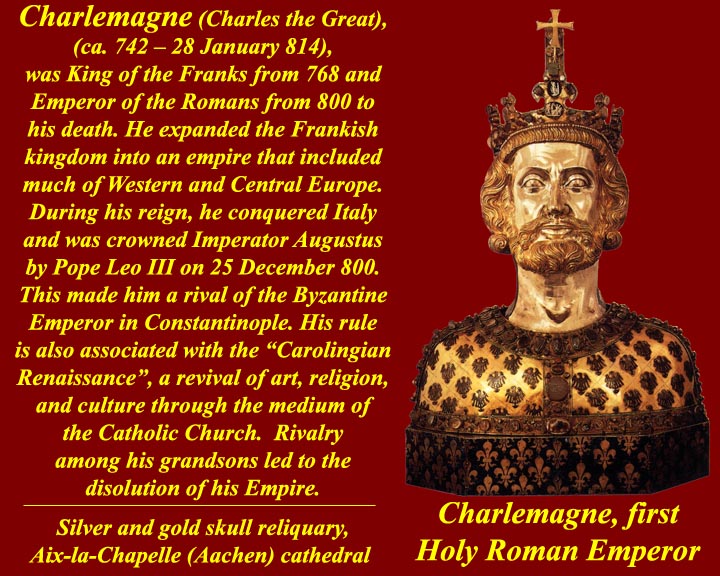

(part of Charlemagne's skull is in the reliquary at Aix-La-Chapelle -- Aachen)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0606CharlemCoronation.jpg

Charlemagne (ca. 742-814) was King of the Franks from 768 and Emperor of the Romans from 800 until his death. During his long reign, he expanded the Frankish kingdom to include most of western and central Europe. He conquered Italy and was crowned by Pope Leo III and acclaimed Imperator and Augustus on 25 December 800 AD. There are two opinions about Charlemagne's prior awareness of the ceremony. Most historians say that Charlemagne or his representatives and the Pope or his representatives had pre-arranged everything. Some historians, however, think that Charlemagne was taken by surprise and did not expect the Pope to place the crown on his head; a papal coronation would presume papal power over Charlemagne. This argument, however, ignores the fact that the earlier coronation of Pepin by Boniface, acting as a Papal Legate, would already have established the same thing. The argument of the "surprise" theorists appear to be that the lack of conclusive evidence of collusion means that there was none. This, of course, makes the question perfect fodder for theses and dissertations any time a new shred of evidence comes to light.

Pope Leo III, the successor of Hadrian I, was deposed in 799 by a group of noble Roman families. He was confined to a monastery but he managed to escape and he eventually reached Charlemagne in Germany to seek his help. Charlemagne escorted the pope back to Rome in November 800 and he eventually convinced the Romans to accept again Leo as their bishop. At the Christmas Mass held in St. Peter's Basilica, Pope Leo crowned Charlemagne and gave him the title of Imperator Romanorum. Whether Charlemagne knew beforehand and had agreed to being appointed emperor is uncertain, whether the pope meant to establish a new Roman empire (the Holy Roman Empire) is uncertain too.

Most likely Pope Leo saw in Charlemagne the new emperor of the only empire he knew, that of Constantinople: in his mind the throne was vacant. Irene, widow of Emperor Leo III, had ruled for years on behalf of her child Constantine VI, but had been ousted from power by her son when he was appointed emperor in 790 at the age of 19. Irene however plotted against her own son, and in 797 Constantine was taken prisoner, his eyes were gouged out, and he was left to die from his wounds. Irene, who had no other sons, reigned on her own, but the pope regarded her as an usurper.

Charlemagne did not make any actual attempt to claim the throne of Constantinople (apart from a possible attempt to marry Irene), and he eventually reached an agreement with Irene's successor on using a slightly different title which avoided frictions between the two powers.

While the immediate effects of Charlemagne's coronation were limited, their long-ranging impact was a major one for the history of Rome, which returned after centuries to have a political role, through the acts of its bishop, whose appointment was no longer subjectto the endorsement of the Byzantine emperor. Charlemagne was regarded by the Roman church as a new Constantine and his statue faces that of the ancient emperor in the porch of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

For more on Charlemagne and his coronation, see

http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/coronation.html and

http://pirate.shu.edu/~wisterro/cdi/0800a_coronation_of_charlemagne.htm

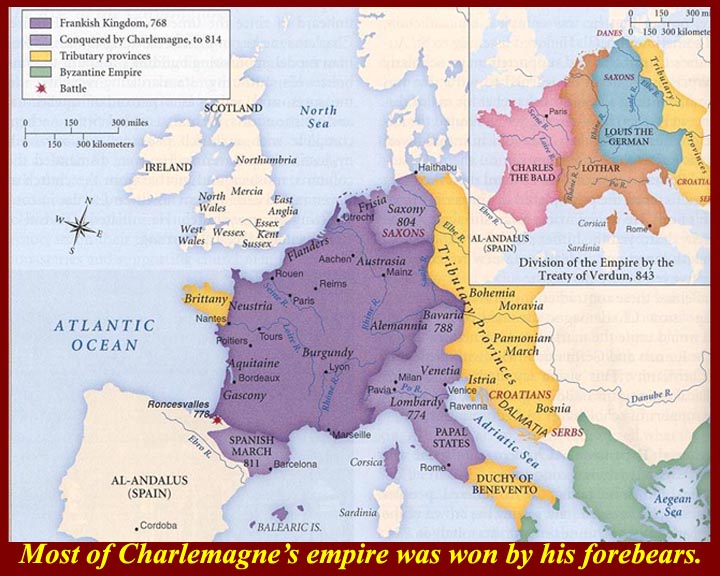

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0606xCharlEmpireMap1.jpg

Although Charlemagne is usually given credit for building the Carolingian empire, it's clear that most of the territory was already controlled by his predecessors. He did manage to extend the borders. And he then tried to break the assembled empire (ex post facto labeled "Carolingia") into pieces for his sons. The Frankish kings adhered to the practice of partible inheritance: dividing their lands among their sons (in the case of kings, it was called divisio regnorum). As was the common practice, Charlemagne set the process in motion before he died.

In 806, Charlemagne made the first provisions for the division of the empire on his death. For Charles the Younger he designated Austrasia and Neustria, Saxony, Burgundy, and Thuringia. To Pepin he gave Italy, Bavaria, and Swabia. Louis received Aquitaine, the Spanish March, and Provence. There was no mention of the imperial title, which has led to the suggestion that, at that time, Charlemagne regarded the title as an honorary achievement which held no hereditary significance.

Charlemagne's division of Carolingia was never to be tested. Pepin died in 810 and Charles in 811. Charlemagne then reconsidered the matter, and in 813, crowned his youngest son, Louis, co-emperor and co-King of the Franks, granting him a half-share of the empire and the rest upon Charlemagne's own death. The only part of the Empire which Louis was not promised was Italy, which Charlemagne specifically bestowed upon Pepin's illegitimate son Bernard. The Empire survived in the possession of Louis, but Louis, called "the Pious", managed to split the empire.

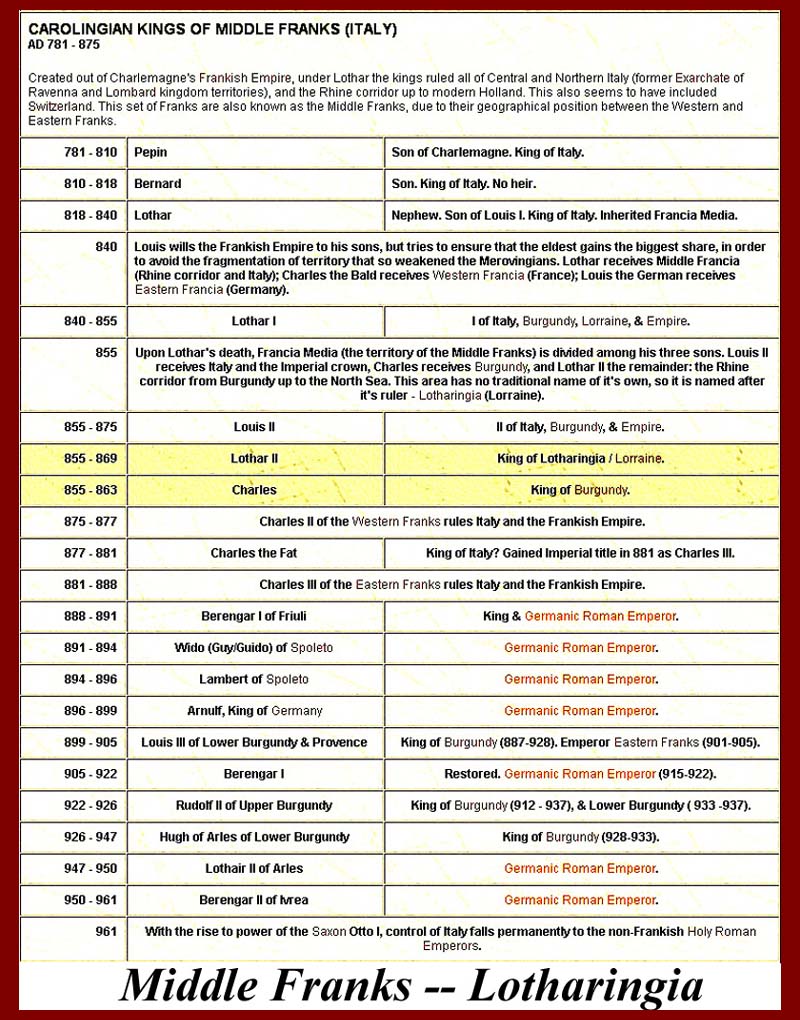

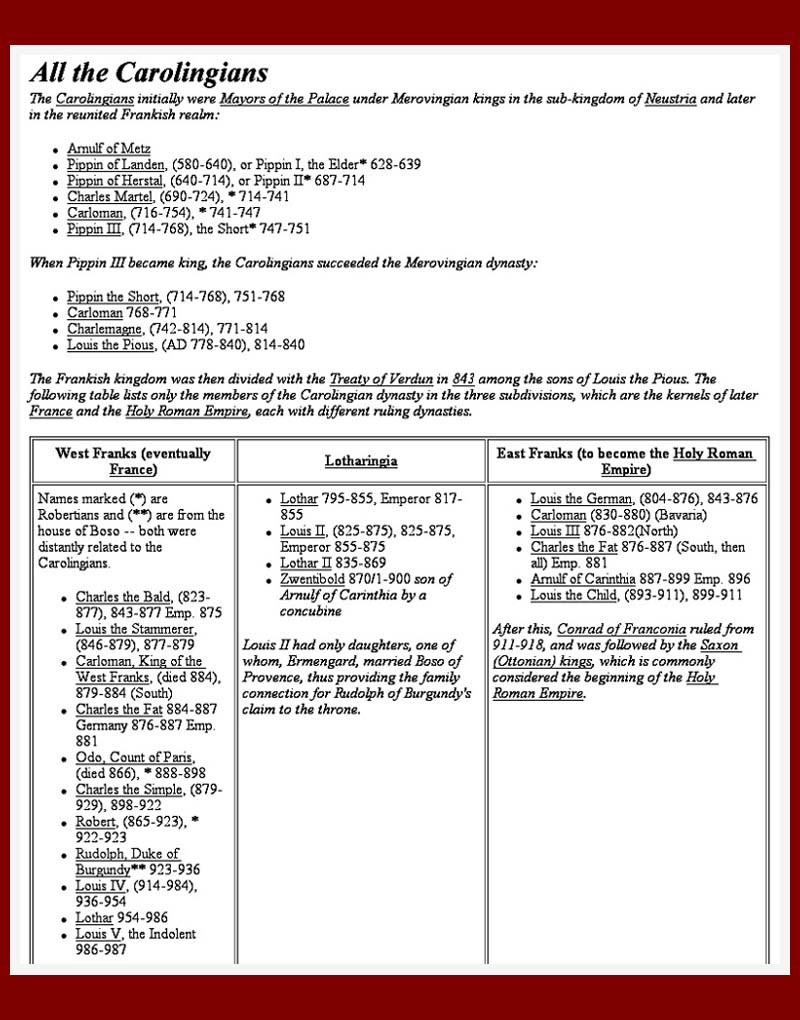

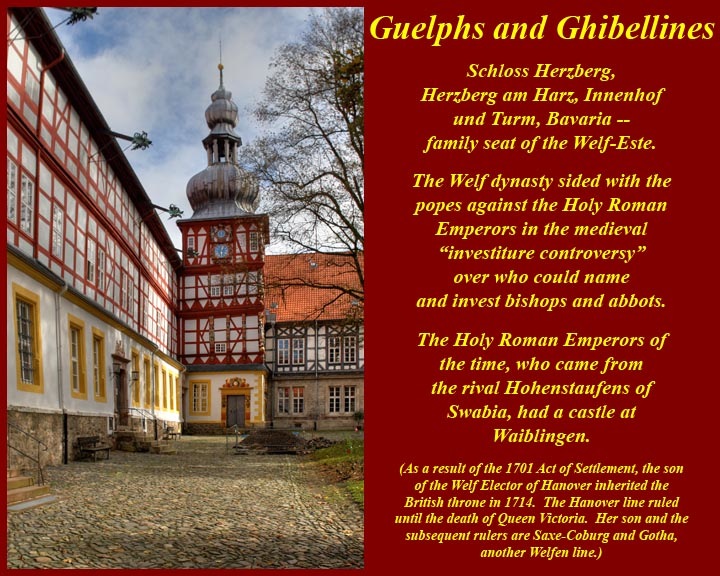

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0607AllCarolingians.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0608DividedCarolingia.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0609CarolDivMap.jpg

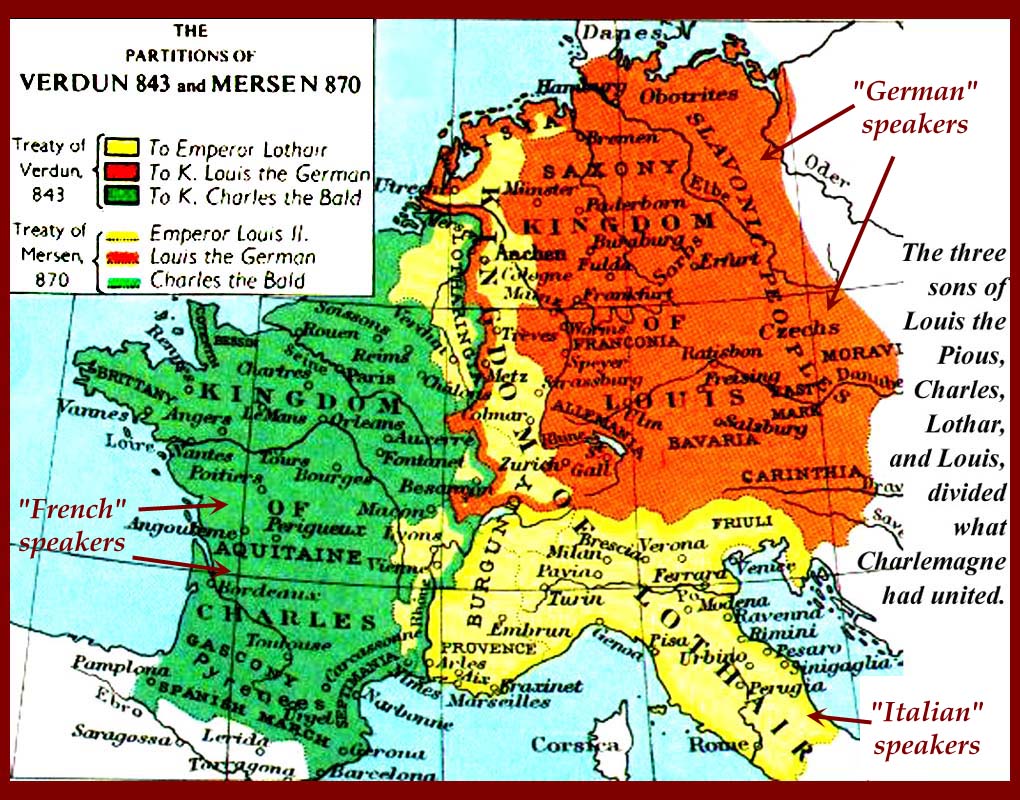

Carolingia had survived Charlemagne, but it didn't survive his son, Louis the Pious.

Louis the Pious (778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair, and the Debonaire. He was the subsidiary King of Aquitaine from 781. In 813, Charlemagne made him King of the Franks and co-Emperor (as Louis I). As the only surviving adult son of Charlemagne, he became the sole ruler of the Franks after his father's death in 814, a position which he held until his death, except for the period 833–34, during which he was deposed.

During his reign in Aquitaine, Louis' job was the defense of his father's southwestern frontier. He reconquered Barcelona from the Muslims in 801 and re-asserted Frankish authority over Pamplona and the Basques south of the Pyrenees in 813. When he became emperor, he included his adult sons in the government (Lothair, Pepin, and Louis) and sought to establish a suitable division of the realm between them. In the 830s his empire was torn by civil war between his sons and for a time Louis was deposed. What had happened was that Louis had remarried and then tried to include his son, Charles, by his second wife, in the succession plans by redividing what he had already set aside for his first three sons. His first three sons disagreed and attacked. Before Louis was able to regain control, Carolingia descended into confusion that is too complicated to consider here (-- see the three civil wars here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_the_Pious#First_civil_war and following for a quick run through). Though his reign ended on a high note, with order largely restored to his empire, it was followed by three additional years of civil war. Louis is generally compared unfavorably to Charlemagne.

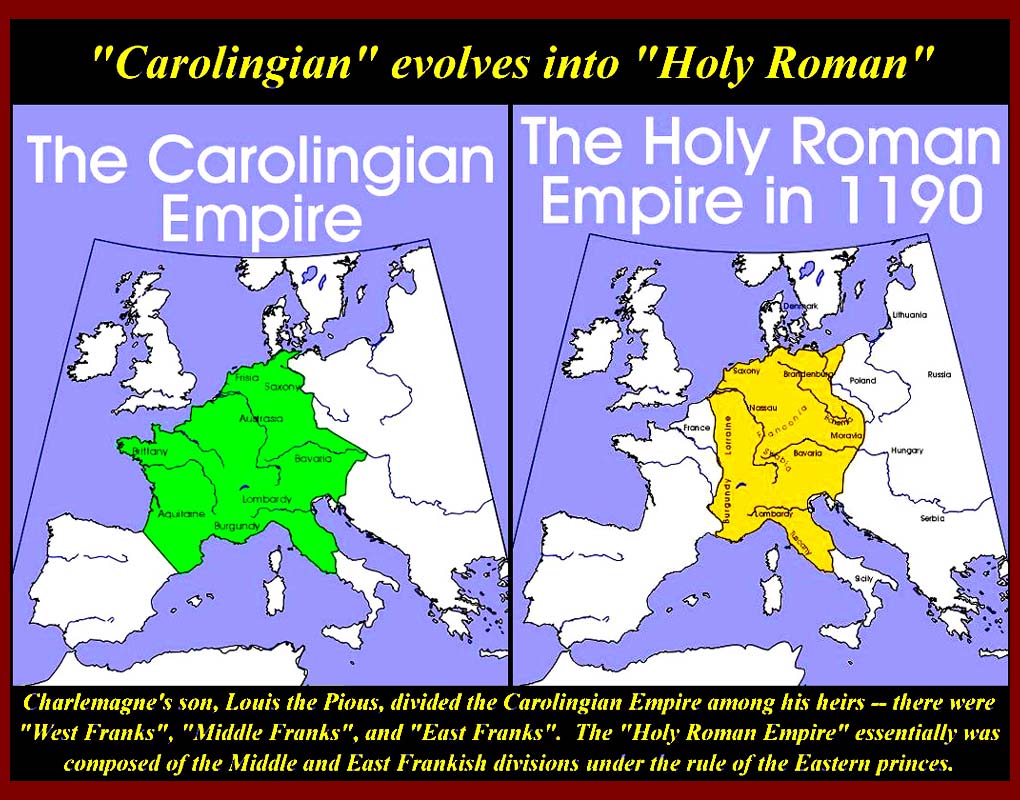

On his death, the last divisio regnorum that Louis had devised went into effect, and Carolingia ceased to exist. The younger son, Charles the Bald, by the second wife got the western section, which became France. The eastern section, which became the Holy Roman Empire (eventually Germany), went to Louis the German. And the middle section, unimaginatively called Lotharingia, was given to Lothair. Lotharingia included Italy north of Naples and a thin strip all the way up to the North Sea. That northern strip was quickly gobbled up by its eastern and western neighbors and was a bone of contention (as Alsace-Lorraine = Elsaß-Lothringen) between France and Germany until World War II.

See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_the_Pious,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_the_Bald, and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_the_German.

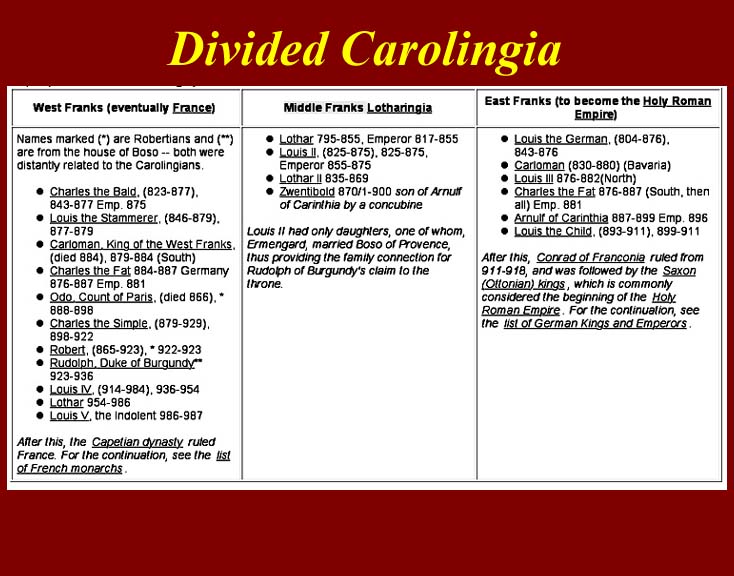

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0610Lothar.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0611LotharingianItaly.jpg

Lothair I or Lothar I (German: Lothar, French: Lothaire, Italian: Lotario) (795 – 29 September 855) was the Emperor of the Romans (817–55), co-ruling with his father until 840, and the King of Bavaria (815–17), Italy (818–55) and Middle Francia (840–55).

As the eldest son of the Carolingian emperor Louis the Pious he eventually inherited the title of Emperor. Before that he had led his full-brothers Pepin I of Aquitaine and Louis the German in revolt against their father on several occasions, in protest against his attempts to make their half-brother Charles the Bald a co-heir to the Frankish domains. Upon the death of the father, Charles and Louis joined forces against Lothair in a three year civil war (840-843), the struggles between the brothers leading directly to the break up of the great Frankish Empire assembled by their grandfather Charlemagne, and would lay the foundation for the development of modern France and Germany. Lothar eventually divided what was left of his section of Carolingia among his own three sons and retired to a monastery. He died there six days later. His eldest son, Louis II received Italy and the title of Emperor. Their heirs formed a long list, but real power in Italy was soon in dispute between two other monarchies, the rulers of the eastern part of the former Carolingian Empire, who were to be the Holy Roman Emperors, and the Papacy.

For information on Lothar, his Lotharingia, and his heirs, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lothair_I and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lotharingia and

http://fmg.ac/Projects/MedLands/LOTHARINGIA.htm.

There is no apparent connection between this Lothair and the later Lothario of Cervantes' Don Quixote.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0612CarolingianToHRE.jpg

The Holy Roman Empire (not really holy or Roman or even an Empire) was Carolingia minus East Francia. It never achieved the political unification that France did.

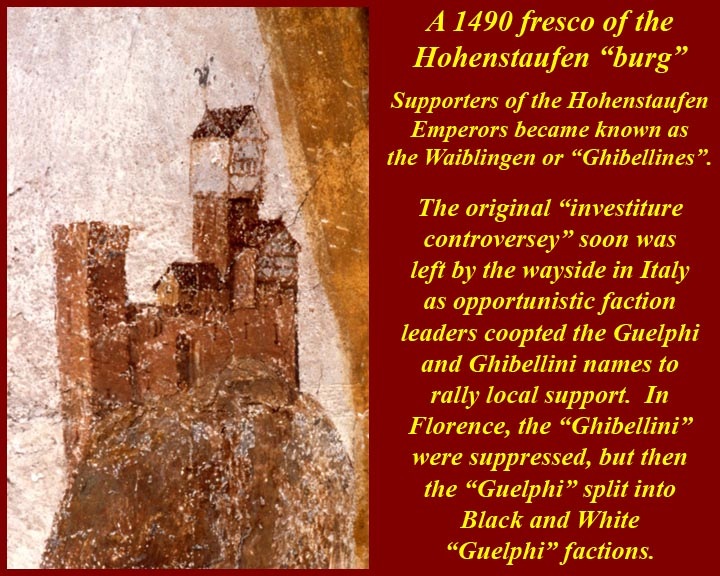

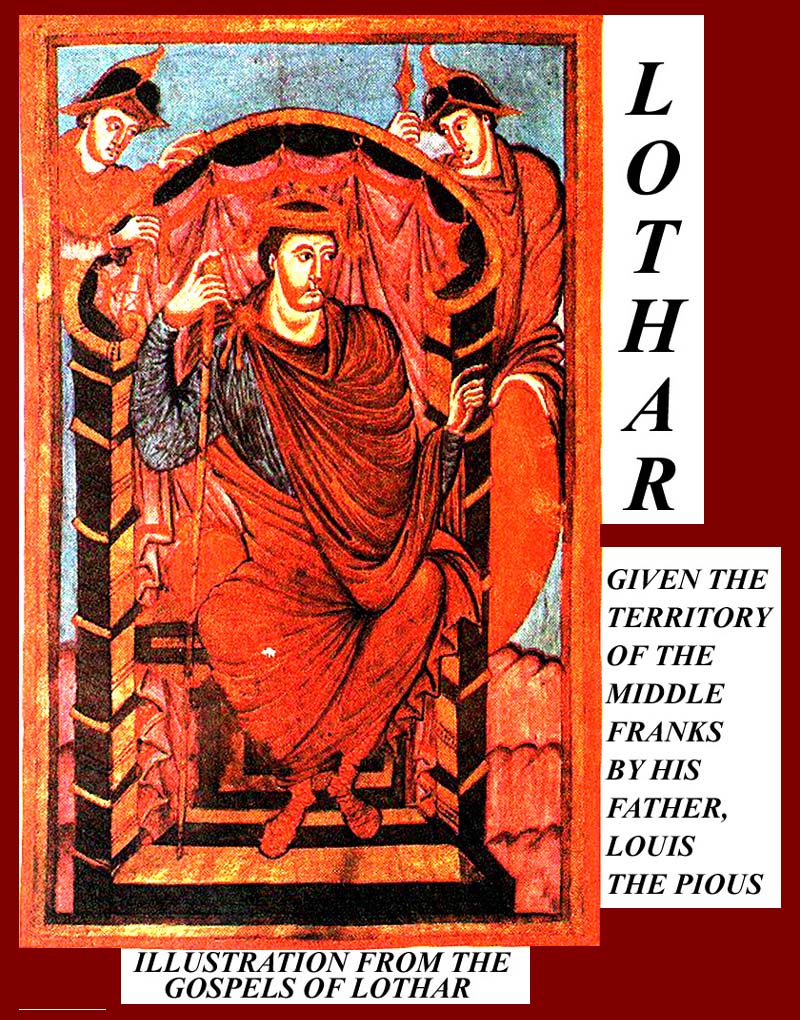

Guelphs and Ghibellines: The names were first used in connection with the rivalry of two princely houses of Germany, the Welfs or Guelphs, who were dukes of Saxony and Bavaria, and the Hohenstaufen (the name Ghibelline is supposedly derived from Waiblingen, a Hohenstaufen castle). The rivalry between the German families, both of which had large holdings in Swabia, dates from their rise to power under Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV (Emperor from 1084-1105). The struggle began in earnest with Henry the Proud and his son and successor, Henry the Lion, and last flared up with the election of Otto IV as Holy Roman emperor. In Italy the party names were perpetuated by rival factions . In succeeding centuries there were constant disputes over the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. In the late medieval period it manifested itself in Italy in conflict between supporters of the Popes (Guelphs) and of the Emperors (Ghibellines).

The division between two distinct "Guelph" and "Ghibelline" parties in Italy became defined during Frederick Barbarossa's reign (12th century) when Frederick conducted military campaigns in Italy to expand imperial power there. Ghibellines were the imperial party, while the Guelphs supported the Pope. Broadly speaking, Guelphs tended to come from wealthy mercantile families, whereas Ghibellines were predominantly those whose wealth was based on agricultural estates. Guelph cities, of course, tended to be in areas where the Emperor was more a threat to local interests than the Pope, and Ghibelline cities tended to be in areas where the enlargement of the Papal States was the more immediate threat. Smaller cities tended to be Ghibelline if the larger city nearby was Guelph, as Guelph Florence and Ghibelline Sienna faced off at the Battle of Montaperti, 1260. Pisa maintained a staunch Ghibelline stance in contraposition to her fiercest rivals, the Guelph Genoa and Florence. Adhesion to one party or another could be therefore motivated by local or regional political reasons. Within cities factions broke down guild by guild, rione by rione, and a city could easily change party after internal upheaval. Moreover, sometimes traditionally Ghibelline cities allied with the Papacy, while Guelph cities were even punished with Papal interdict.

After the Guelphs finally defeated the Ghibellines in 1289 at Campaldino and Caprona, Guelphs began to fight among themselves. By 1300 Florence was divided into the Black Guelphs and the White Guelphs. The Blacks continued to support the Papacy, while the Whites were opposed to Papal influence, specifically the influence of Pope Boniface VIII. Dante was among the supporters of the White Guelphs, and in 1302 he was exiled when the Black Guelphs took control of Florence. Those who were not connected to either side, or who had no connections to either Guelphs or Ghibellines, considered both factions unworthy of support but were still affected by the changes of power in their respective cities. Emperor Henry VII was disgusted by supporters of both sides when he visited Italy in 1310, and in 1334 Pope Benedict XII threatened excommunication to anyone who used either name.

It should be noted that Italians did not use the terms Guelph and Ghibellines much until about 1250, and then only in Tuscany (where they originated), with the names "church party" and "imperial party" preferred in some areas.

For the Holy Roman Empire and Emperors, see

http://www.heraldica.org/topics/national/hre.htm,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holy_Roman_Empire, and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holy_Roman_Emperor.

The British royal family stems from the House of Hanover and ultimately from the Welf house. The Hanoverians are a German royal dynasty which has ruled the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg (German: Braunschweig-Lüneburg), the Kingdom of Hanover and the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland. It succeeded the House of Stuart as monarchs of Great Britain and Ireland in 1714 and held that office until the death of Victoria in 1901. They are sometimes referred to as the House of Brunswick and Lüneburg, Hanover line. The House of Hanover is a younger branch of the House of Welf, which in turn is the senior branch of the House of Este.

Queen Victoria was the granddaughter of George III, and was a descendant of most major European royal houses. She arranged marriages for her children and grandchildren across the continent, tying Europe together; this earned her the nickname "the grandmother of Europe". She was the last British monarch of the House of Hanover; her son King Edward VII belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the line of his father, Prince Albert. Since Victoria could not inherit the German kingdom and duchies under Salic law, those possessions passed to the next eligible male heir, her uncle Ernest Augustus I of Hanover, the Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale—the fifth son of George III. In the United Kingdom, during World War I, King George V changed the house's name from Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to the currently used name "House of Windsor" in 1917.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0620a-GuelphsGhibellines1.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0620b-GuelphsGhibellines2.jpg

For an article on Guephs and Ghibellines in the Italian context, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guelphs_and_Ghibellines.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0620cRomeoJuliet.jpg

The most famous Guelph and Ghibeline families in western literature.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0613ChurchAndState.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0614ChristCrowns.jpg

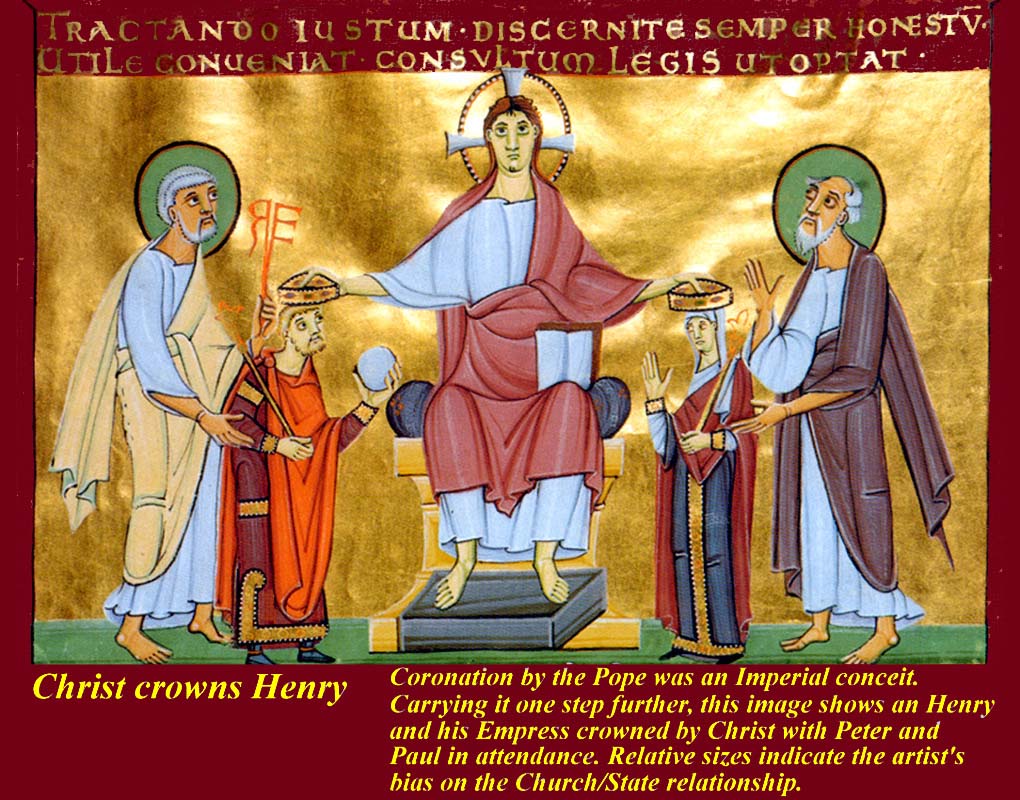

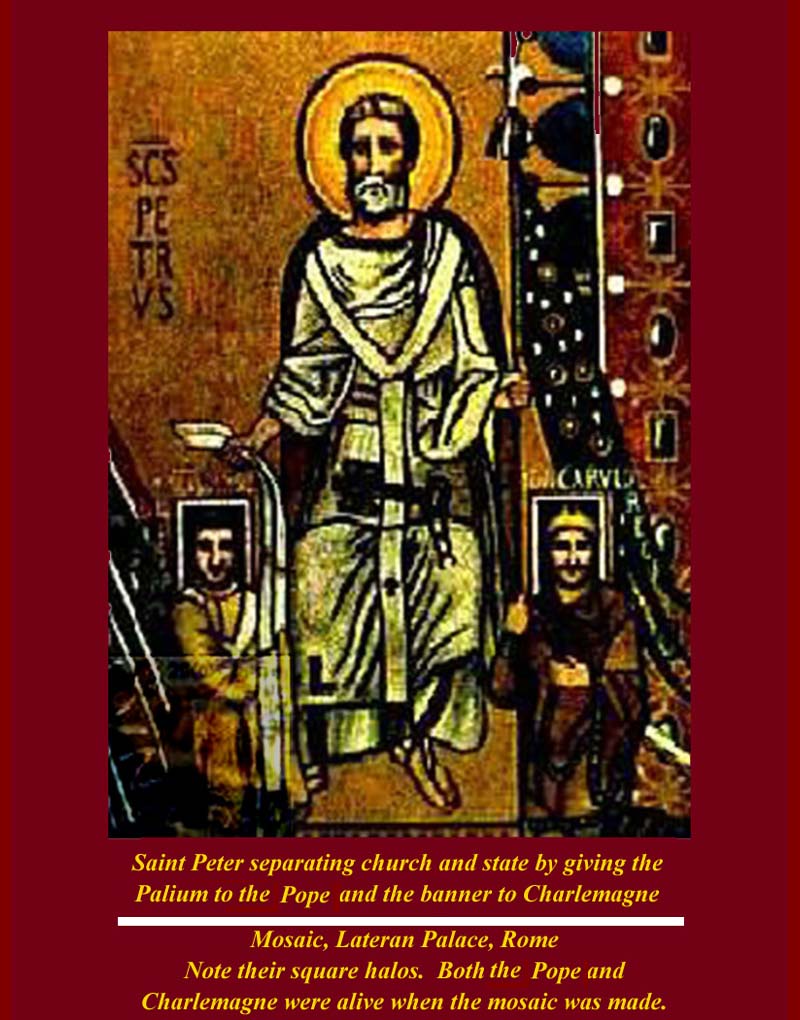

As we have already seen, Roman church art always contained a healthy dose of propaganda. Initially, this was aimed at proving Papal primacy over eastern Christian Patriarchs and especially the Patriarch of Constantinople. When the Popes' rivals for authority became the Holy Roman Emperors in the late medieval period, art was used to show a clear definition of papal and imperial power as in the first image above. The

second image demonstrates the relative importance that the church ascribed to temporal rulers. This propagandist pattern in art continued: during the Counter-Reformation when the great Jesuit headquarters church in Rome, The Gesu, was built, the figure that dominates the right side of the altar dedicated to Ignatius Loyola is a female personified Faith casting out heretics -- easily recognizable images of Luther and Jan Hus (see http://www.thais.it/scultura/image/ALTE/SB_511.jpg.)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0615Regalia.jpg

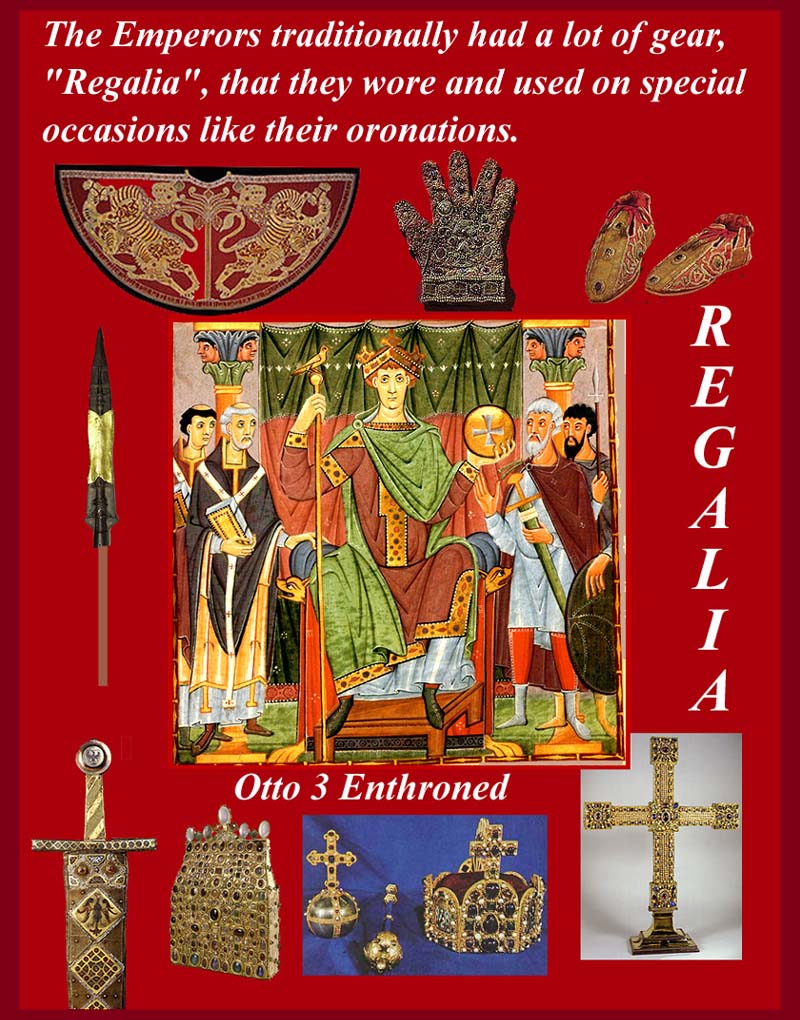

"Regalia"-- A well dressed Emperor may or may not have new clothes, but he does need to accessorize. Capes, gloves, shoes, spears, swords, purses, orbs, crowns, crosses, staffs-with-birds-on-top all apparently were necessary for public appearances, not to mention a crowd of attentive attendants (see how they all lean in?)

See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Regalia

A short-lived Carolingian Renaissance clearly occurred throughout Carolingia. Its shortness was due, of course, to the fact that the political situation rapidly deteriorated and resources were diverted to intra- and inter-group warfare. The Carolingian Renaissance, short as it was, produced recognizable and durable results in architecture, art, education, and legibility.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0616SCecilia.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0617SCeciliaApseMosai.jpg

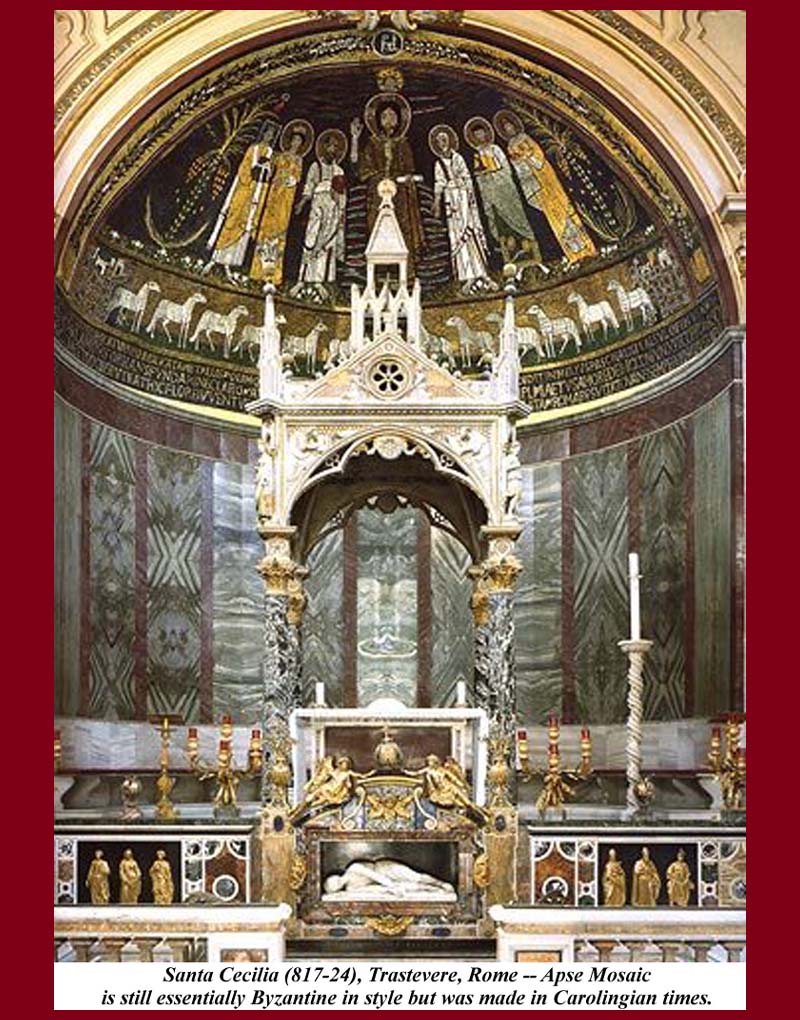

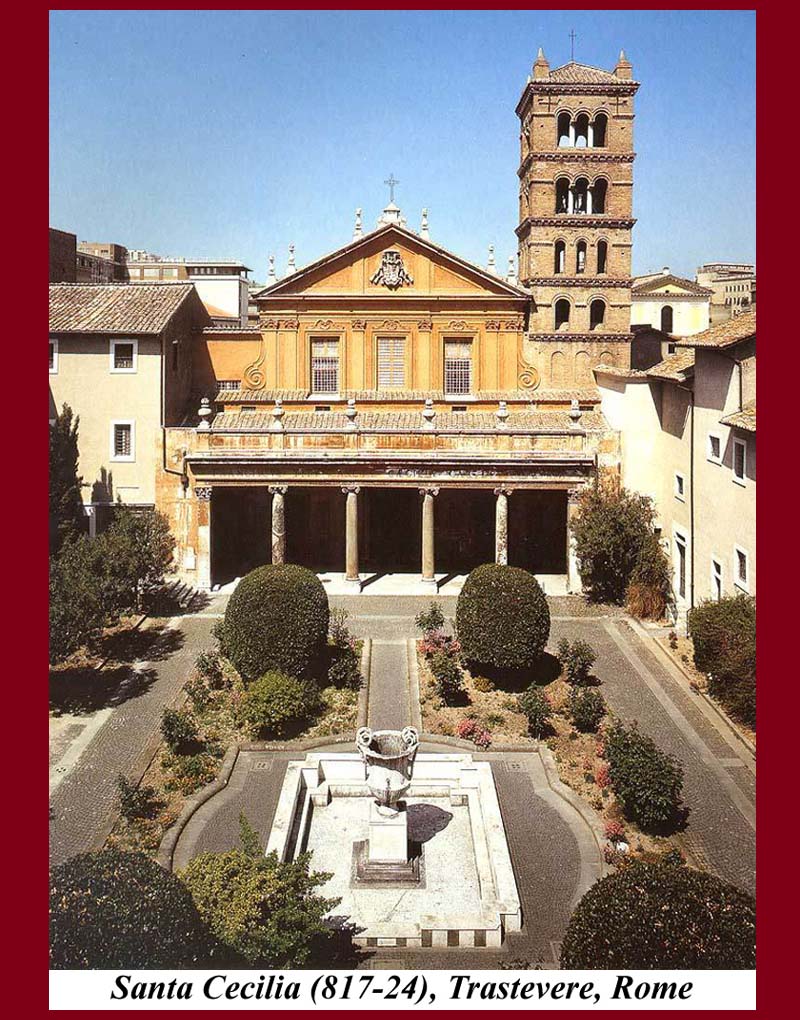

Santa Cecilia Church in Trastevere is the best surviving example in Rome of ecclesiastical architecture of the period. It exterior pretty much looks as it did when it was built, having escaped later modifications (although the curly volutes at the sides above the porch are baroque and the bell tower=campanile is 12th century -- the interior, however, is much modified with only the apse mosaic surviving). The church is dedicated to the patron saint of music and musicians, so it is the site of frequent concerts.

The apse above the choir is decorated with a fine 9th-century mosaic. It depicts a standing figure of Christ, flanked by Pope Paschal I, St. Agatha, and St. Paul on the left and St. Peter, St. Valerian and St. Cecilia on the right against a background of a meadow with flowers, palm trees and sunset-lit clouds. Below the figures are twelve sheep, the Lamb of God, and a lengthy dedicatory inscription from Paschal I.

For a description of the Santa Cecelia church, see

http://www.sacred-destinations.com/italy/rome-santa-cecilia

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0618SPrassedeApseMosa.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0619SPrassedeInt.jpg

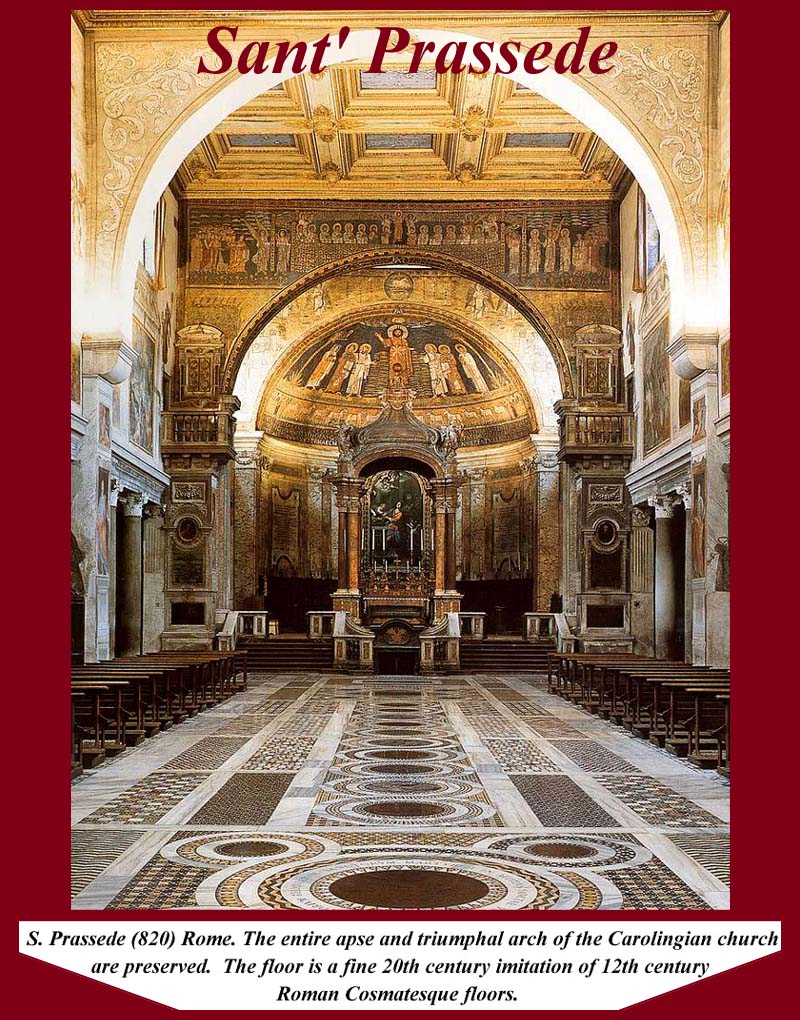

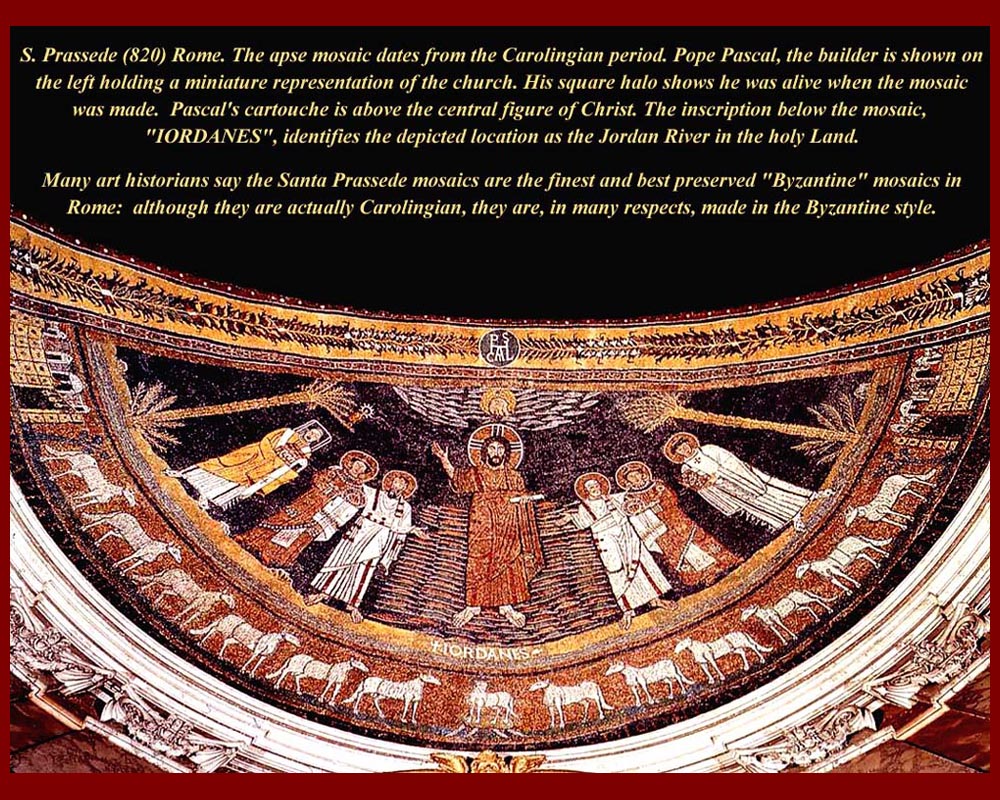

Santa Prassede Church has an apse mosaic with the same subject as the mosaic in Santa Cecelia. This church was also built by Pascal I around 820 AD. It contains the fine apse mosaic, contemporary mosaics on the triumphal arch that frames the apse, and the mosaics of the Zeno Chapel which Pascal commissioned as a funerary chapel for his mother.

For a description of this church, see

http://www.sacred-destinations.com/italy/rome-santa-prassede.

Images of the Zeno chapel mosaics can be found in Unit 9 of this course (http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRomUnit0900-0PixList.html).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0619xAlcuinCharlemagne.jpg

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0619yCarolingianScript.jpg

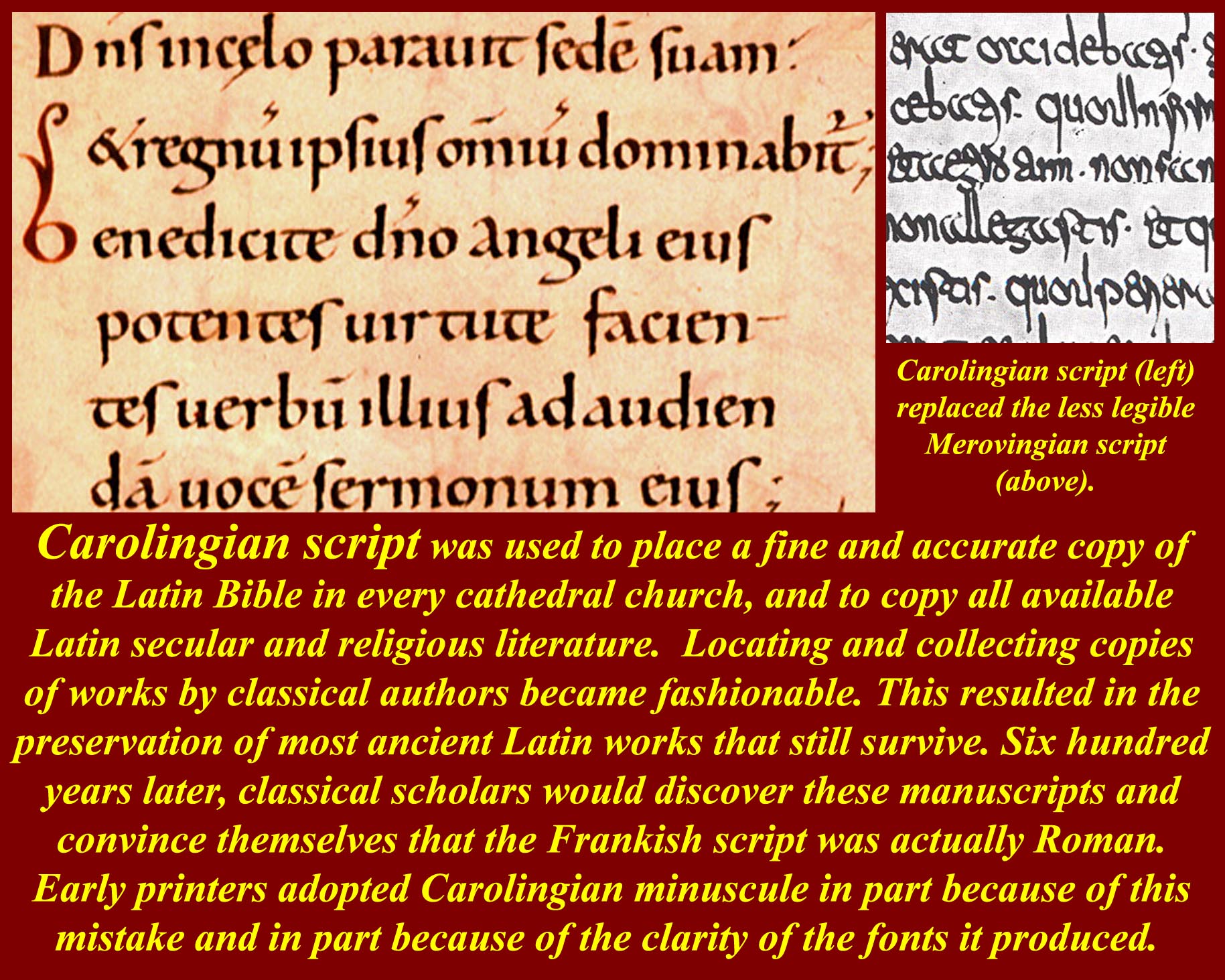

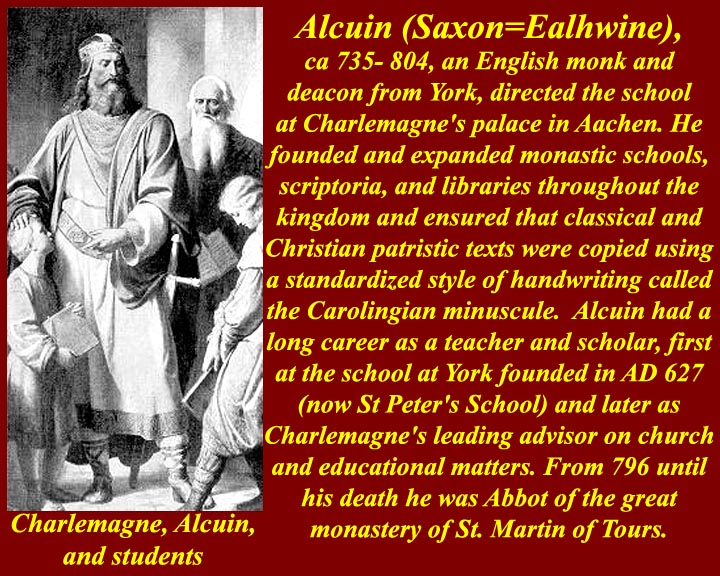

Alcuin (Saxon=Ealhwine)(730s or 740s – May 19, 804) was an English scholar, ecclesiastic, poet and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was the foremost scholar of the revival of learning known as the Carolingian Renaissance. He was born around 735 and became the student of Archbishop Ecgbert at York. At the invitation of Charlemagne, he became a leading scholar and teacher at the Carolingian court, where he remained a figure in the 780s and 790s. He was the most distinguished of a group of scholars that Charlemagne gathered around himself, including also Peter of Pisa, Paulinus of Aquileia, Rado, and Abbot Fulrad.

From 782-790, Alcuin taught Charlemagne himself, his sons Pepin and Louis, the young men sent to be educated at court and the young clerics attached to the palace chapel. Alcuin revolutionized the educational standards of the Palace School, introducing Charlemagne to the liberal arts and creating a personalized atmosphere of scholarship and learning, to the extent that the institution came to be known as the 'school of Master Albinus'.

Alcuin founded and expanded monastic schools, scriptoria, and libraries throughout Charlemagne's kingdom and ensured that classical and Christian Patristic texts were copied using a standardized handwriting style called Carolingian miniscule. The classical texts, when found later by Renaissance philologists, were originally thought to be classical Roman original manuscripts. That mistaken identification was abandoned after comparison with copies in Carolingian miniscule of Patristic texts that had been composed after Roman times.

Unfortunately many of Alcuin's educational and textual reforms were lost when the Carolingian state shattered. If not for Divisio Regnorum which killed off the Carolingian Renaissance, the Renaissance might have flowered hundreds of years earlier.

For information on Alcuin, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alcuin and

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01276a.htm.

For Alcuin's River-Crossing Math/Logic puzzle (with solution), see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fox,_goose_and_bag_of_beans_puzzle.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/MedRom0620dFrancisII-LastEmperor.jpg

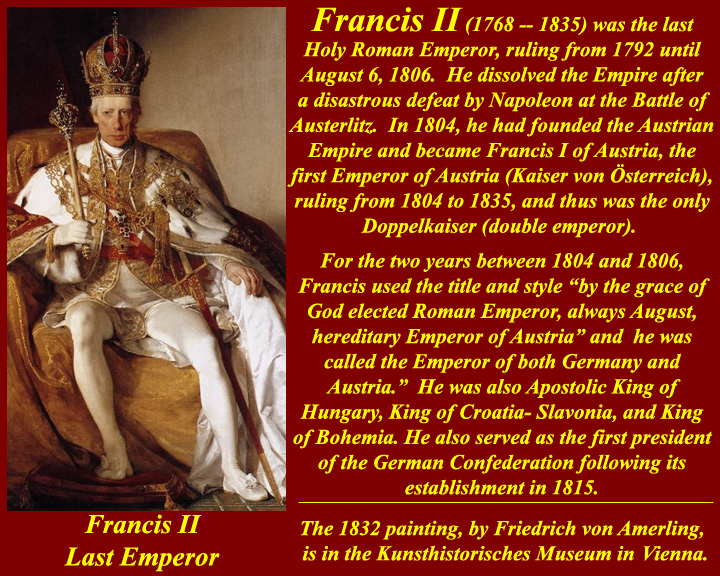

Last Emperor and Doppelkaiser Francis II (1768-1835).

Francis ruled as the Last Holy Roman Emperor from 1792 until 1806. He dissolved the Holy Roman Empire after a disastrous defeat by Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz. Francis I continued his leading role as an opponent of Napoleonic France in the Napoleonic Wars, and suffered several more defeats after Austerlitz.

In 1804, he had founded the Austrian Empire and became Francis I of Austria (Franz I), the first Emperor of Austria (Kaiser von Österreich), ruling from 1804 to 1835, so later he was named the one and only Doppelkaiser (double emperor) in history. For the two years between 1804 and 1806, Francis used the title and style "by the grace of God elected Roman Emperor, always August, hereditary Emperor of Austria" and he was called the Emperor of both Germany and Austria. He was also Apostolic King of Hungary as I. Ferenc, King of Croatia-Slavonia as Franjo II, and King of Bohemia as Francis I ("František I").

After 1806 he used the titles: "We, Francis the First, by the grace of God Emperor of Austria; King of Jerusalem, Hungary, Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Galicia and Lodomeria; Archduke of Austria; Duke of Lorraine, Salzburg, Würzburg, Franconia, Styria, Carinthia and Carniola; Grand Duke of Cracow; Grand Prince of Transylvania; Margrave of Moravia; Duke of Sandomir, Masovia, Lublin, Upper and Lower Silesia, Auschwitz and Zator, Teschen and Friule; Prince of Berchtesgaden and Mergentheim; Princely Count of Habsburg, Gorizia and Gradisca and of the Tirol; and Margrave of Upper and Lower Lusatia and in Istria, President of the German Confederation".

He served as the first president of the German Confederation following its establishment in 1815.

On 2 March 1835, 43 years and a day after his father's death, Francis died in Vienna of a sudden fever aged 67.

For more on the last Holy Roman Emperor, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_II,_Holy_Roman_Emperor.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/medRom0621Franks.jpg

Other Distinguished Franks.