San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

St. Charles of the Four Fountains

The "Carlino"Corner of Via del Quirinale and Via delle Quattro Fontane, Rome

There is a story, dating from a later time when Francesco Borromini and Gianlorenzo Bernini were serious rivals for all of the big architectural commissions in Rome, that tells of Bernini arranging the Carlino commission for Borromini just to remove Borromini from the construction site at St. Peter's in the Vatican. It is true that Borromini stopped attacking Bernini's work at St. Peter's after work on the Carlino began: Bernini, according to Borromini's previous public accusations, had stolen Borromini's engineering ideas for St Peter's, ideas Borromini had developed as chief assistant and construction supervisor when his "Uncle" Carlo Maderno had been in charge of the St. Peter's project. Borromini undoubtedly still believed that he, instead of Bernini, should have succeeded Maderno as the master builder at St. Peter's when Maderno died in 1629. Whether it was a Bernini ploy, as the legend says, or not, it's clear that Borromini was therafter thoroughly absorbed by his enthusiasm for the Carlino, which was his first independent project and which, by his own testimony, was always his favorite project.

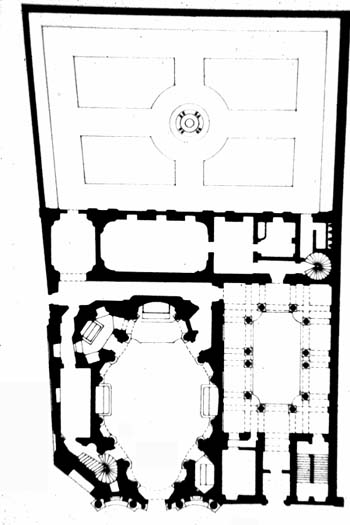

The fact that the entirety of the Carlino could easily fit within the floor-plan of any of the four great piers that support the dome of St. Peter's led to another legend that the plan and proportions of the Carlino were based on the plan and proportions of one of the piers. But, in reality, the plan is a novel masterpiece of Borrominian inventiveness, and the tiny plot of land owned by the Trinitarians dictated the proportions.

There wasn't enough room to build either a "Greek Cross" (four equal arms) or "Latin Cross" (longer base leg) church, so Borromini used two equilateral triangles joined base-to-base as his plan. He placed the door at one end of the long axis of this diamond shaped pattern and an apse with the main altar at the other. An additional altar at each end of the short axis -- where the two triangles joined -- completed the basic structure. Of course, Borromini fluted and recurved the sides, and used false perspective in the coffered ceilings to make the entranceway, apse and side altars look deeper. He also used elegant long columns whose lines continued upward into the oval dome, added his trademark cherubs, and did almost everything in stark white stucco. There are side rooms (most notably a sacristy and a refectory), passageways, a cloister with its ambulatory, a garden in the rear, quarters for the monks, a spiral stairway up to the bell tower -- everything a monastery would have. This is all designed by Borromini, so none of it is trivial, but it's all just a setting for the real gem: it is the church itself, the Carlino, which is considered by many architects and art historians as the most perfect of all baroque structures. Although the whole complex was designed by Francesco Borromini, some parts of the work -- the façade and bell tower -- were actually completed by his nephew and heir, Bernardo Borromini, after Francesco committed suicide in 1667. Borromini had started the façade and tower only a few years earlier, so the Carlino represented both his first and his last architectural work.

The church is dedicated to St. Charles Borromeo and the Holy Trinity. Besides being Borromini's first independent commission, it also was the first church in Rome to be dedicated to Charles Borromeo, who had been canonized in 1610. It has always belonged to the Spanish Trinitarian order of monks ("Discalced", or "shoeless"), an order dedicated to the freeing of Christian slaves. The "Quattro Fontane" in the name of the church refers to the four fountains at the corners of the intersection where the church stands. The figures shown in the fountains are two River gods and two goddesses: the reclining male figure with the tree in the background is the Arno River, and the reclining male with reeds (no tree) is the Tiber; the reclining female with a tree is Juno, and the reclining female with no tree is Diana.

The façade is in travertine and is integrated with that of the monastery. It also curves around the corner and incorporates the pre-existing fountain of the Arno River god. It is on two levels. Above the doorway, a niche is crowned by a tympanon formed by the wings of two angels. Beneath the wings is a statue of St Charles Borromeo by Antonio Raggi. On the sides are statues of St. John of Matha and St. Felix of Valois, the founders of the Trinitarian Order. As is usual on Borromini façades, there are curves and projections, pillars, volutes and balustrades.

The interior was embellished in later years, adding color to the altars, but the church still is mostly white. The fresco above the altar, by Pierre Mignard, also has a depiction of Sts. Charles Borromeo, John of Matha and Felix of Valois. The mummified body of a martyred Roman soldier lies in the chapel on the left side. The painting in the chapel is by Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, and depicts the Flight to Egypt. In the sacristy is a porcelain holy-water stoup attributed to Borromini. A room outside the sacristy was set aside for Borromini's tomb, but it remains empty. After his suicide, Borromini's remains were not allowed to be entombed in the church. (He was not, however, denied burial in consecrated soil -- like Maderno, he is entombed in the church of S.Giovanni dei Fiorentini.)

The refectory, a dining room for the monks, has a 1611 painting of St Charles Borromeo, by Orazio Borgianni, which may have been painted originally as an altarpiece for the main altar in the church. There are also beautiful stucco decorations.

Until the time that he died, Borromini kept his promise to the Trinitarian monks that he would never submit a bill for his work on their church.

The Church is located at Via del Quirinale 23 on the intersection with Via dele Quattro Fontane. It opens about 9:30 on weekday mornings, but you may have to ring the bell at the monastery entrance which is a few meters to the right of the church entrance. Like many other Rome churches, the Carlino usually closes at about 1230 or 1 o'clock while the sacristan and the monks take a long lunch and reopens later in the afternoon.

P.S.: Borromini's real name was Francesco Castelli. He was one of the many "Luganese stone workers" -- architects, sculptors, artisans, and masons -- from Lugano in the Duchy of Lombardy, who worked in Rome during the Baroque period (and Maderno, the godfather of the Baroque was another, born in the same Luganese town, Bissone (now in the Swiss Canton of Ticino, which juts southward into Italian Lombardy)). He worked under the name Borromini, it was said, as a sign of his reverence for St. Charles Borromeo, another Lombard.

P.S. 2: Borromini's cherubs were different from the "putti" (naked little kids with wings) that others were using at the time. Borromini profusely used the now more common "smiling head and wings" format. Cherubs, by the way, were not always the loveable little-kid things we all know. The biblical description (Ezekiel 1:4-28) is more like this: their basic form is that of a human biped (1:5), but they have four faces (1:6) and four wings (1:6). Their feet look something like those of a calf (cloven hooves?) and are shiny, as if they are made of burnished bronze (1:7). The four wings are spread out, one on each of their four sides. Under each wing is what looks like a human hand (1:8). Their heads have four faces, one on each of the four sides (1:10). One face looked human, one resembled an ox, one a lion, and one an eagle (1:10). (These four facial forms later became the icons of the four Christian evangelists -- cherubim were often cast as messengers.) As a result of having a face on each side of their bodies, they didn't have to turn to change direction; no matter which way they decided to go, they were already facing that way (1:9, 12). The sound their wings made was quite loud and frightening(1:24). When a cherub appeared to someone, one of the first things he had to say was "don't be afraid". Not surprising.

Internet links:

As might be expected, because of its reputation as the finest and most elegant baroque church in Rome, the Carlino is well documented on the Internet.

The best description I have found on the Internet of the church and its history is the Joseph Connors paper "Un teorema sacro: San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane" -- although the title is in Italian, the paper is in English: http://www.columbia.edu/~jc65/cvlinks/teorema.htm.

Borromini's dark and melancholy life is documented in another Joseph Connors piece at http://www.columbia.edu/~jc65/cvlinks/vita.html. (Professor Connors is a former Director of the American Academy in Rome [1988-92] and one of the world's greatest authorities on Borromini. His Internet Site at http://www.columbia.edu/~jc65/main.html has links to a number of his articles on Borromini.)

As is often the case, the best Internet site for images of the art and architecture of this church and its complex is at http://rubens.anu.edu.au/popolo/midjpg/alphabetical/00131.html. Follow "next page" links for eight additional page of images.

Links to more pix and drawings can be found at http://webcampus3.stthomas.edu/jmjoncas/LiturgicalStudiesInternetLinks/ChristianWorship/Architecture/Centuries/CWArchitecture1600_1700CE/SCarlo4Fontane.html.

For good images of the four fountains at the intersection, go to http://www.romeartlover.it/Vasi35b.html.

A German language site at http://www.biblhertz.it/Mitarbeiter/schlimme/san_carlino/san_carlino.html demonstrates how CAD (Computer Aided Design) is used to study architecture, using the Carlino façade as the prototype.

Good as all these images are, they can not, of course, compare with seeing the real thing.

Go to http://www.mmdtkw.org/Veneto2002.html for other articles.