This page is on the internet at http://www.mmdtkw.org/GR--Unit17-ClassicalGreekPhilosophy-Readings.html

Readings for Ancient Greece 2 --

Unit 17, Classical Greek Philosophy

[Text

in colored

letters are

Internet links; click on links to go to

additional information. Use your

web browser "back" or "return" link to

come back to this page.]

For Pre-Socratic Philosophers,

c.f.,

http://www.mmdtkw.org/GR-Unit8-PreSocraticsGames--Readings.html

and http://www.mmdtkw.org/GR-Unit8-PreSocraticsGames.html

Contents:

1.

Ancient Greek Philosophy (from Internet

Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

2. Ancient Greek Philosophy (from

Wikipedia)

3. Socrates (from Wikipedia)

3a. Criticism of

Socratic thought (from Wikipedia)

4. Plato

(from Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

5. Aristotle (from Internet

Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

5a.

Peripatetic School (from Wikipedia)

6. Stoicism (from

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

7. Epicureanism (from

Wikipedia)

8. Ancient Greek Skepticism

(from Internet Encyclopedia of

Philosophy)

9. Neoplatonism (from

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

10. Islamic Neoplatonism (from Islamic

Philosophy Online)

11. Neoplatonism and

Christianity (from Wikipedia)

12. List of important Ancient Greek Philosophers (from

http://www.greek-islands.us/ancient-greece/greek-philosophers/)

1.

Ancient Greek Philosophy

From:

Internet Encyclopedia of

Philosophy, http://www.iep.utm.edu/greekphi/

The Ancient Greek philosophers have played a pivotal

role in the shaping of the western philosophical

tradition. This article surveys the seminal works

and ideas of key figures in the Ancient Greek

philosophical tradition from the Presocratics to the

Neoplatonists. It highlights their main

philosophical concerns and the evolution in their

thought from the sixth century BC to the sixth

century AD.

The Ancient Greek philosophers have played a pivotal

role in the shaping of the western philosophical

tradition. This article surveys the seminal works

and ideas of key figures in the Ancient Greek

philosophical tradition from the Presocratics to the

Neoplatonists. It highlights their main

philosophical concerns and the evolution in their

thought from the sixth century BC to the sixth

century AD.

The

Ancient Greek philosophical tradition broke away

from a mythological approach to explaining the

world, and it initiated an approach based on reason

and evidence. Initially concerned with explaining

the entire cosmos, the Presocratic philosophers

strived to identify its single underlying principle.

Their theories were diverse and none achieved a

consensus, yet their legacy was the initiation of

the quest to identify underlying principles.

This

sparked a series of investigations into the limit

and role of reason and of our sensory faculties, how

knowledge is acquired and what knowledge consists

of. Here we find the Greek creation of philosophy as

“the love of wisdom,” and the birth of metaphysics,

epistemology, and ethics. Socrates,

Plato,

and Aristotle

were the most influential of the ancient Greek

philosophers, and they focused their attention more

on the role of the human being than on the

explanation of the material world. The work of these

key philosophers was succeeded by the Stoics and

Epicureans who were also concerned with practical

aspects of philosophy and the attainment of

happiness. Other notable successors are Pyrrho's

school of skepticism

and the Neoplatonists such as Plotinus

who tried to unify Plato's thought with theology.

Table

of Contents

- Presocratics

- Socrates

and his Followers

- Plato

- Aristotle

- Stoicism

- Epicureanism

- Skepticism

- Neoplatonism

1. Presocratics

The

Western philosophical tradition began in ancient

Greece in the 6th century BCE. The first

philosophers are called "Presocratics" which

designates that they came before Socrates. The

Presocratics were from either the eastern or western

regions of the Greek world. Athens -- home of

Socrates, Plato and Aristotle

-- is in the central Greek region and was late in

joining the philosophical game. The Presocratic's

most distinguishing feature is emphasis on questions

of physics; indeed, Aristotle

refers to them as "Investigators of Nature". Their

scientific interests included mathematics,

astronomy, and biology. As the first philosophers,

though, they emphasized the rational unity of

things, and rejected mythological explanations of

the world. Only fragments of the original writings

of the Presocratics survive, in some cases merely a

single sentence. The knowledge we have of them

derives from accounts of early philosophers, such as

Aristotle's Physics and Metaphysics,

The Opinions of the Physicists by

Aristotle's pupil Theophratus, and Simplicius, a

Neoplatonist who compiled existing quotes.

The

first group of Presocratic philosophers were from

Ionia. The Ionian philosophers sought the material

principle (archê) of things, and the mode

of their origin and disappearance. Thales

of Miletus (about 640 BCE) is reputed the father of

Greek philosophy. He declared water to be the basis

of all things. Next came Anaximander

of Miletus (about 611-547 BCE), the first writer on

philosophy. He assumed as the first principle an

undefined, unlimited substance (to apeiron)itself

without qualities, out of which the primary

opposites, hot and cold, moist and dry, became

differentiated. His countryman and younger

contemporary, Anaximenes,

took for his principle air, conceiving it as

modified, by thickening and thinning, into fire,

wind, clouds, water, and earth. Heraclitus

of Ephesus (about 535-475 BCE) assumed as the

principle of substance aetherial fire. From fire all

things originate, and return to it again by a

never-resting process of development. All things,

therefore, are in a perpetual flux. However, this

perpetual flux is structured by logos--

which most basically means 'word,' but can also

designate 'argument,' 'logic,' or 'reason' more

generally. The logos which structures the

human soul mirrors the logos which

structures the ever-changing processes of the

universe.

Philosophy

was first brought into connection with practical

life by Pythagoras

of Samos (about 582-504 BCE), from whom it received

its name: "the love of wisdom". Regarding the world

as perfect harmony, dependent on number, he aimed at

inducing humankind likewise to lead a harmonious

life. His doctrine was adopted and extended by a

large following of Pythagoreans, including Damon,

especially in Lower Italy.

That

country was also the home of the Eleatic doctrine of

the One, called after the town of Elea, the

headquarters of the school. It was founded by Xenophanes

of Colophon (born about 570 BCE), the father of

pantheism, who declared God to be the eternal unity,

permeating the universe, and governing it by his

thought. His great disciple, Parmenides

of Elea (born about 511), affirmed the one

unchanging existence to be alone true and capable of

being conceived, and multitude and change to be an

appearance without reality. This doctrine was

defended by his younger countryman Zeno

in a polemic against the common opinion, which sees

in things multitude, becoming, and change. Zeno

propounded a number of celebrated paradoxes, much

debated by later philosophers, which try to show

that supposing that there is any change or

multiplicity leads to contradictions. The primary

legacy of Zeno is that subsequent scholars became

very aware of the difficulty of properly handling

the concept of infinity.

Empedocles

of Agrigentum (born 492 BCE) appears to have been

partly in agreement with the Eleatic School, partly

in opposition to it. On the one hand, he maintained

the unchangeable nature of substance; on the other,

he supposes a plurality of such substances -- i. e.

the four elements, earth, water, air, and fire. Of

these the world is built up, by the agency of two

ideal principles as motive forces -- namely, love as

the cause of union, strife as the cause of

separation. Empedocles was also the first person to

propound an evolutionary account of the development

of species.

Anaxagoras

of Clazomenae (born about 500 BCE) also maintained

the existence of an ordering principle as well as a

material substance, and while regarding the latter

as an infinite multitude of imperishable primary

elements, qualitatively distinguished, he conceived

divine reason or Mind (nous) as ordering

them. He referred all generation and disappearance

to mixture and resolution respectively. To him

belongs the credit of first establishing philosophy

at Athens, in which city it reached its highest

development, and continued to have its home for one

thousand years without intermission.

The

first explicitly materialistic system was formed by

Leucippus

(fifth century BCE) and his pupil Democritus

of Abdera (born about 460 BCE). This was the

doctrine of atoms -- literally 'uncuttables' --

small primary bodies infinite in number, indivisible

and imperishable, qualitatively similar, but

distinguished by their shapes. Moving eternally

through the infinite void, they collide and unite,

thus generating objects which differ in accordance

with the varieties, in number, size, shape, and

arrangement, of the atoms which compose them.

The

efforts of all these earlier philosophers had been

directed somewhat exclusively to the investigation

of the ultimate basis and essential nature of the

external world. Hence their conceptions of human

knowledge, arising out of their theories as to the

constitution of things, had been no less various.

The Eleatics, for example, had been compelled to

deny that senses give one any access to the truth,

since to the world of sense, with its multitude and

change, they allowed only a phenomenal existence.

However, reason can give one knowledge of what the

One is like--or, more accurately, what it is not

like.

Retaining

the skepticism of the Eleatics about the senses,

while rejecting their doctrines about the ability of

reason to reach truth apart from the senses, the Sophists

held that all thought rests solely on the

apprehensions of these senses and on subjective

impression, and that therefore we have no other

standards of action than convention for the

individual. Specializing in rhetoric, the Sophists

were more professional educators than philosophers.

They flourished as a result of a special need for at

that time for Greek education. Prominent Sophists

include Protagoras,

Gorgias,

Hippias,

and Prodicus.

2. Socrates and his Followers

A

new period of philosophy opens with the Athenian

Socrates (469-399 BCE). Like the Sophists, he

rejected entirely the physical speculations in which

his predecessors had indulged, and made the thoughts

and opinions of people his starting-point; but

whereas it was the thoughts of and opinions of the

individual that the Sophists took for the standard,

Socrates questioned people relentlessly about their

beliefs. He tried to find the definitions of the

virtues, such as courage and justice, by

cross-examining people who professed to have

knowledge of them. His method of cross-examining

people, the elenchus, did not succeed in

establishing what the virtues really were, but

rather it exposed the ignorance of his

interlocutors.

Socrates

was an enormously magnetic figure, who attracted

many followers, but he also made many enemies.

Socrates was executed for corrupting the youth of

Athens and for disbelieving in the gods of the city.

This philosophical martyrdom, however, simply made

Socrates an even more iconic figure than would have

been otherwise, and many later philosophical schools

took Socrates as their hero.

Of

Socrates' numerous disciples many either added

nothing to his doctrine, or developed it in a

one-sided manner, by confining themselves

exclusively either to dialectic or to ethics. Thus

the Athenian Xenophon

contented himself, in a series of writings, with

exhibiting the portrait of his master to the best of

his comprehension, and added nothing original. The

Megarian School, founded by Euclides

of Megara, devoted themselves almost entirely to

dialectic investigation of the one Good. Stilpo

of Megara became the most distinguished member of

the school. Ethics predominated both with the Cynics

and Cyrenaics,

although their positions were in direct opposition.

Antisthenes

of Athens, the founder of the Cynics,

conceived the highest good to be the virtue which

spurns every enjoyment. Cynicism continued in Greece

with Menippus and on to Roman times through the

efforts of Demonax

and others. Aristippus

of Cyrene, the founder of the Cyrenaics,considered

pleasure to be the sole end in life, and regarded

virtue as a good only in so far as it contributed to

pleasure.

3. Plato

Both

aspects of the genius of Socrates were first united

in Plato of Athens (428-348 BCE), who also combined

with them many the principles established by earlier

philosophers, and developed the whole of this

material into the unity of a comprehensive system.

The groundwork of Plato's scheme, though nowhere

expressly stated by him, is the threefold division

of philosophy into dialectic, ethics, and physics;

its central point is the theory of forms. This

theory is a combination of the Eleatic doctrine of

the One with Heraclitus's theory of a perpetual flux

and with the Socratic method of concepts. The

multitude of objects of sense, being involved in

perpetual change, are thereby deprived of all

genuine existence. The only true being in them is

founded upon the forms, the eternal, unchangeable

(independent of all that is accidental, and

therefore perfect) archetypes, of which the

particular objects of sense are imperfect copies.

The quantity of the forms is defined by the number

of universal concepts which can be derived from the

particular objects of sense.

The

highest form is that of the Good, which is the

ultimate basis of the rest, and the first cause of

being and knowledge. Apprehensions derived from the

impression of sense can never give us the knowledge

of true being -- i.e. of the forms. It can only be

obtained by the soul's activity within itself, apart

from the troubles and disturbances of sense; that is

to say, by the exercise of reason. Dialectic, as the

instrument in this process, leading us to knowledge

of the ideas, and finally of the highest idea of the

Good, is the first of sciences (scientia

scientiarum). In physics, Plato adhered

(though not without original modifications) to the

views of the Pythagoreans, making Nature a harmonic

unity in multiplicity. His ethics are founded

throughout on the Socratic; with him, too, virtue is

knowledge, the cognition of the supreme form of the

Good. And since in this cognition the three parts of

the soul -- cognitive, spirited, and appetitive --

all have their share, we get the three virtues:

Wisdom, Courage, and Temperance or Continence. The

bond which unites the other virtues is the virtue of

Justice, by which each several part of the soul is

confined to the performance of its proper function.

The

school founded by Plato, called the Academy

(from the name of the grove of the Attic hero

Academus where he used to deliver his lectures)

continued for long after. In regard to the main

tendencies of its members, it was divided into the

three periods of the Old, Middle, and New Academy.

The chief personages in the first of these were

Speusippus (son of Plato's sister), who succeeded

him as the head of the school (till 339 BCE), and

Xenocrates of Chalcedon (till 314 BCE). Both of them

sought to fuse Pythagorean speculations on number

with Plato's theory of ideas. The two other

Academies were still further removed from the

specific doctrines of Plato, and advocated skepticism.

4. Aristotle

The

most important among Plato's disciples is Aristotle

of Stagira (384-322 BCE), who shares with his

master the title of the greatest philosopher of

antiquity. But whereas Plato had sought to elucidate

and explain things from the supra-sensual standpoint

of the forms, his pupil preferred to start from the

facts given us by experience. Philosophy to him

meant science, and its aim was the recognition of

the purpose in all things. Hence he establishes the

ultimate grounds of things inductively -- that is to

say, by a posteriori conclusions from a

number of facts to a universal. In the series of

works collected under the name of Organon,

Aristotle

sets forth the laws by which the human understanding

effects conclusions from the particular to the

knowledge of the universal.

Like

Plato, he recognizes the true being of things in

their concepts, but denies any separate existence of

the concept apart from the particular objects of

sense. They are inseparable as matter and form. In

matter and form, Aristotle

sees the fundamental principles of being. Matter is

the basis of all that exists; it comprises the

potentiality of everything, but of itself is not

actually anything. A determinate thing only comes

into being when the potentiality in matter is

converted into actuality. This is effected by form,

inherent in the unified object and the completion of

the potentiality latent in the matter. Although it

has no existence apart form the particulars, yet, in

rank and estimation, form stands first; it is of its

own nature the most knowable, the only true object

of knowledge. For matter without any form cannot

exist, but the essential definitions of a common

form, in which are included the particular objects

may be separated from matter. Form and matter are

relative terms, and the lower form constitutes the

matter of a higher (e.g. body, soul, reason). This

series culminates in pure, immaterial form, the

Deity, the origin of all motion, and therefore of

the generation of actual form out of potential

matter.

All

motion takes place in space and time; for space is

the potentiality, time the measure of the motion.

Living beings are those which have in them a moving

principle, or soul. In plants the function of soul

is nutrition (including reproduction); in animals,

nutrition and sensation; in humans, nutrition,

sensation, and intellectual activity. The perfect

form of the human soul is reason separated from all

connection with the body, hence fulfilling its

activity without the help of any corporeal organ,

and so imperishable. By reason the apprehensions,

which are formed in the soul by external

sense-impressions, and may be true or false, are

converted into knowledge. For reason alone can

attain to truth either in cognition or action.

Impulse towards the good is a part of human nature,

and on this is founded virtue; for Aristotle

does not, with Plato, regard virtue as knowledge

pure and simple, but as founded on nature, habit,

and reason. Of the particular virtues (of which

there are as many as there are contingencies in

life), each is the apprehension, by means of reason,

of the proper mean between two extremes which are

not virtues -- e.g. courage is the mean between

cowardice and foolhardiness. The end of human

activity, or the highest good, is happiness, or

perfect and reasonable activity in a perfect life.

To this, however, external goods are more of less

necessary conditions.

The

followers of Aristotle, known as Peripatetics

(Theophrastus

of Lesbos, Eudemus of Rhodes, Strato of Lampsacus,

etc.), to a great extent abandoned metaphysical

speculation, some in favor of natural science,

others of a more popular treatment of ethics,

introducing many changes into the Aristotelian

doctrine in a naturalistic direction. A return to

the views of the founder first appears among the

later Peripatetics, who did good service as

expositors of Aristotle's works, such as Avicenna

and Averroes.

The

Peripatetic School tended to make philosophy the

exclusive property of the learned class, thereby

depriving it of its power to benefit a wider circle.

This soon produced a negative reaction, and

philosophers returned to the practical standpoint of

Socratic ethics. The speculations of the learned

were only admitted in philosophy where serviceable

for ethics. The chief consideration was how to

popularize doctrines, and to provide the individual,

in a time of general confusion and dissolution, with

a fixed moral basis for practical life.

5. Stoicism

Such

were the aims of Stoicism,

founded by Athens about 310 by Zeno of Citium (in

Cyprus), and brought to fuller systematic form by

his successors a heads of the school, Cleanthes

of Assos, and especially Chrysippus

of Soli, who died about 206. Important Stoic

writers of the Roman period include Epictetus

and Marcus Aurelius. Their doctrines contained

little that was new, seeking rather to give a

practical application to the dogmas which they took

ready-made from previous systems. With them

philosophy is the science of the principles on which

the moral life ought to be founded. The only

allowable effort is towards the attainment of

knowledge of human and divine things, in order to

thereby regulate life. The method to lead men to

true knowledge is provided by logic; physics

embraces the doctrines as to the nature and

organization of the universe; ethics draws from them

its conclusions for practical life. Regarding Stoic

logic, all knowledge originates in the real

impressions of things on the senses, which the soul,

being at birth a blank slate, receives in the form

of presentations. These presentations, when

confirmed by repeated experience, are

syllogistically developed by the understanding into

concepts. The test of their truth is the convincing

or persuasive force with which they impress

themselves upon the soul.

In

physics the foundation of the Stoic

doctrine was the dogma that all true being is

corporeal. Within the corporeal they recognized two

principles, matter and force -- that is, the

material, and the Deity (logos, order,

fate) permeating and informing it. Ultimately,

however, the two are identical. There is nothing in

the world with any independent existence: all is

bound together by an unalterable chain of causation.

The agreement of human action with the law of

nature, of the human will with the divine will, or

life according to nature, is virtue, the chief good

and highest end in life. It is essentially one, the

particular or cardinal virtues of Plato being only

different aspects of it; it is completely sufficient

for happiness, and incapable of any differences of

degree. All good actions are absolutely equal in

merit, and so are all bad actions. All that lies

between virtue and vice is neither good nor bad; at

most, it is distinguished as preferable,

undesirable, or absolutely indifferent. Virtue is

fully possessed only by the wise person, who is no

way inferior in worth to Zeus; he is lord over his

own life, and may end it by his own free choice. In

general, the prominent characteristic of Stoic

philosophy is moral heroism, often verging on

asceticism.

6. Epicureanism

The

same goal which was aimed at in Stoicism was also

approached, from a diametrically opposite position,

in the system founded about the same time by Epicurus,

of the deme Gargettus in Attica (342-268), who

brought it to completion himself. Epicureanism, like

Stoicism, is connected with previous systems. Like

Stoicism, it is also practical in its ends,

proposing to find in reason and knowledge the secret

of a happy life, and admitting abstruse learning

only where it serves the ends of practical wisdom.

Hence, logic (called by Epicurus (kanonikon),

or the doctrine of canons of truth) is made entirely

subservient to physics, physics to ethics. The

standards of knowledge and canons of truth in

theoretical matters are the impressions of the

senses, which are true and indisputable, together

with the presentations formed from such impressions,

and opinions extending beyond those impressions, in

so far as they are supported or not contradicted by

the evidence of the senses. In practical questions

the feelings of pleasure and pain are the tests.

Epicurus's physics, in which he follows in

essentials the materialistic system of Democritus,

are intended to refer all phenomena to a natural

cause, in order that a knowledge of nature may set

men free from the bondage of disquieting

superstitions.

In

ethics he followed within certain limits the Cyrenaic

doctrine, conceiving the highest good to be

happiness, and happiness to be found in pleasure, to

which the natural impulses of every being are

directed. But the aim is not with him, as it is with

the Cyrenaics,

the pleasure of the moment, but the enduring

condition of pleasure, which, in its essence, is

freedom from the greatest of evils, pain. Pleasures

and pains are, however, distinguished not merely in

degree, but in kind. The renunciation of a pleasure

or endurance of a pain is often a means to a greater

pleasure; and since pleasures of sense are

subordinate to the pleasures of the mind, the

undisturbed peace of the mind is a higher good than

the freedom of the body from pain. Virtue is

desirable not for itself, but for the sake of

pleasure of mind, which it secures by freeing people

from trouble and fear and moderating their passions

and appetites. The cardinal virtue is prudence,

which is shown by true insight in calculation the

consequences of our actions as regards pleasure or

pain.

7. Skepticism

The

practical tendency of Stoicism and Epicureanism,

seen in the search for happiness, is also apparent

in the Skeptical School founded by Pyrrho

of Elis (about 365-275 BCE). Pyrrho disputes the

possibility of attaining truth by sensory

apprehension, reason, or the two combined, and

thence infers the necessity of total suspension of

judgment on things. Thus can we attain release from

all bondage to theories, a condition which is

followed, like a shadow, by that imperturbable state

of mind which is the foundation of true happiness.

Pyrrho's immediate disciple was Timon.

Pyrrho's doctrine was adopted by the Middle and New

Academies (see above), represented by Arcesilaus of

Pitane (316-241 BCE) and Carneades

of Cyrene (214-129 BCE) respectively. Both attacked

the Stoics for asserting a criterion of truth in our

knowledge; although their views were indeed

skeptical, they seem to have considered that what

they were maintaining was a genuine tenet of

Socrates and Plato.

The

latest Academics, such as Antiochus of Ascalon

(about 80 BCE), fused with Platonism certain

Peripatetic and many Stoic dogmas, thus making way

for Eclecticism,

to which all later antiquity tended after Greek

philosophy had spread itself over the Roman world. Roman

philosophy, thus, becomes an extension of the

Greek tradition. After the Christian era

Pythagoreanism, in a resuscitated form, again takes

its place among the more important systems.

Pyrrhonian skepticism

was also re-introduced by Aenesidemus,

and developed further by Sextus Empiricus. But the

preeminence of this period belongs to Platonism,

which is notably represented in the works of

Plutarch of Chaeronea and the physician Galen.

8. Neoplatonism

The

closing period of Greek philosophy is marked in the

third century CE. by the establishment of Neoplatonism

in Rome. Its founder was Plotinus

of Lycopolis in Egypt (205-270) and its emphasis is

a scientific philosophy of religion, in which the

doctrine of Plato is fused with the most important

elements in the Aristotelian

and Stoic

systems and with Eastern speculations. At the summit

of existences stands the One or the Good, as the

source of all things. It emanates from itself, as if

from the reflection of its own being, reason,

wherein is contained the infinite store of ideas.

Soul, the copy of the reason, is emanated by and

contained in it, as reason is in the One, and, by

informing matter in itself non-existence,

constitutes bodies whose existence is contained in

soul. Nature, therefore, is a whole, endowed with

life and soul. Soul, being chained to matter, longs

to escape from the bondage of the body and return to

its original source. In virtue and philosophic

thought soul had the power to elevate itself above

the reason into a state of ecstasy, where it can

behold, or ascend up to, that one good primary Being

whom reason cannot know. To attain this union with

the Good, or God, is the true function of humans, to

whom the external world should be absolutely

indifferent.

Plotinus's

most important disciple, the Syrian Porphyry,

contented himself with popularizing his master's

doctrine. But the school if Iamblichus, a disciple

of Porphyry, effected a change in the position of

Neoplatonism, which now took up the cause of

polytheism against Christianity, and adopted for

this purpose every conceivable form of superstition,

especially those of the East. Foiled in the attempt

to resuscitate the old beliefs, its supporters then

turned with fresh ardor to scientific work, and

especially to the study of Plato and Aristotle,

in the interpretation of whose works they rendered

great services. The last home of philosophy was at

Athens, where Proclus (411-485) sought to reduce to

a kind of system the whole mass of philosophic

tradition, until in 529 CE, the teaching of

philosophy at Athens was forbidden by Justinian.

--------------------------

2.

Ancient Greek philosophy

Ancient

Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BCE and

continued throughout the Hellenistic period

and the period in which Ancient Greece was part

of the Roman Empire. It dealt with

a wide variety of subjects, including political philosophy,

ethics, metaphysics, ontology, logic, biology, rhetoric, and aesthetics.

Many philosophers today concede

that Greek philosophy has influenced much of Western culture since

its inception. Alfred North

Whitehead once noted: "The safest general

characterization of the European philosophical tradition

is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato."[1]

Clear, unbroken lines of influence lead from ancient Greek and Hellenistic

philosophers to Early Islamic

philosophy, the European Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment.

Some

claim that Greek philosophy, in turn, was influenced

by the older wisdom literature and mythological

cosmogonies of the ancient Near East. Martin Litchfield

West gives qualified assent to this view,

stating, "contact with oriental cosmology and theology helped to liberate the

early Greek

philosophers' imagination; it certainly gave

them many suggestive ideas. But they taught themselves

to reason. Philosophy as we understand it is a Greek

creation."[2]

Subsequent

philosophic tradition was so influenced by Socrates (as presented by Plato) that it is conventional to

refer to philosophy developed prior to Socrates as pre-Socratic

philosophy. The periods following this until the

wars of

Alexander the Great are those of "classical

Greek" and "Hellenistic" philosophy.

Pre-Socratic

philosophy

The

convention of terming those philosophers

who were active prior to Socrates the pre-Socratics

gained currency with the 1903 publication of Hermann Diels' Fragmente

der Vorsokratiker, although the term did not

originate with him.[3]

The term is considered philosophically useful because

what came to be known as the "Athenian school"

(composed of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle) signaled a profound

shift in the subject matter and methods of philosophy;

Friedrich Nietzsche's

thesis that this shift began with Plato rather than

with Socrates (hence his nomenclature of "pre-Platonic

philosophy") has not prevented the predominance of the

"pre-Socratic" distinction.[4]

The

pre-Socratics were primarily concerned with cosmology, ontology and mathematics. They were

distinguished from "non-philosophers" insofar as they

rejected mythological explanations in favor of

reasoned discourse.[5]

Milesian

school

Thales

of Miletus, regarded by Aristotle as the first

philosopher,[6]

held that all things arise from water.[7]

It is not because he gave a cosmogony that John Burnet

calls him the "first man of science," but because he

gave a naturalistic explanation of the cosmos and supported it with

reasons.[8]

According to tradition, Thales was able to predict an

eclipse and taught the

Egyptians how to measure the height of the pyramids.[9]

Thales

inspired the Milesian school of

philosophy and was followed by Anaximander, who argued that

the substratum or arche could not be water or

any of the classical elements but

was instead something "unlimited" or "indefinite" (in

Greek, the apeiron). He

began from the observation that the world seems to

consist of opposites (e.g., hot and cold), yet a thing

can become its opposite (e.g., a hot thing cold).

Therefore, they cannot truly be opposites but rather

must both be manifestations of some underlying unity

that is neither. This underlying unity (substratum, arche)

could not be any of the classical elements, since they

were one extreme or another. For example, water is

wet, the opposite of dry, while fire is dry, the

opposite of wet.[10]

Anaximenes in turn

held that the arche was air, although John

Burnet argues that by this he meant that it was a

transparent mist, the aether.[11]

Despite their varied answers, the Milesian school was

searching for a natural substance that would remain

unchanged despite appearing in different forms, and

thus represents one of the first scientific attempts

to answer the question that would lead to the

development of modern atomic theory; "the Milesians,"

says Burnet, "asked for the φύσις of all things."[12]

Xenophanes

Xenophanes

was born in Ionia, where the Milesian school

was at its most powerful, and may have picked up some

of the Milesians' cosmological theories as a result.[13]

What is known is that he argued that each of the

phenomena had a natural rather than divine explanation

in a manner reminiscent of Anaximander's theories and

that there was only one god, the world as a whole, and

that he ridiculed the anthropomorphism of the

Greek religion by claiming that cattle would claim

that the gods looked like cattle, horses like horses,

and lions like lions, just as the Ethiopians claimed

that the gods were snubnosed and black and the

Thracians claimed they were pale and red-haired.[14]

Burnet

says that Xenophanes was not, however, a scientific

man, with many of his "naturalistic" explanations

having no further support than that they render the

Homeric gods superfluous or foolish.[15]

He has been claimed as an influence on Eleatic philosophy, although

that is disputed, and a precursor to Epicurus, a representative of a

total break between science and religion.[16]

Pythagoreanism

Main article: Pythagoreanism

Pythagoras lived at roughly

the same time that Xenophanes did and, in contrast to

the latter, the school that he founded sought to

reconcile religious belief and reason. Little is known

about his life with any reliability, however, and no

writings of his survive, so it is possible that he was

simply a mystic whose successors

introduced rationalism into Pythagoreanism, that he

was simply a rationalist whose successors

are responsible for the mysticism in Pythagoreanism,

or that he was actually the author of the doctrine;

there is no way to know for certain.[17]

Pythagoras

is said to have been a disciple of Anaximander and to have

imbibed the cosmological concerns of the

Ionians, including the idea that the cosmos is

constructed of spheres, the importance of the

infinite, and that air or aether is the arche

of everything.[18]

Pythagoreanism also incorporated ascetic ideals, emphasizing

purgation, metempsychosis, and

consequently a respect for all animal life; much was

made of the correspondence between mathematics and the

cosmos in a musical harmony.[19]

Heraclitus

Heraclitus

must have lived after Xenophanes and Pythagoras, as he

condemns them along with Homer as proving that much

learning cannot teach a man to think; since Parmenides refers to him in

the past tense, this would place him in the 5th

century BCE.[20]

Contrary to the Milesian school, who

would have one stable element at the root of all,

Heraclitus taught that "everything flows" or

"everything is in flux," the closest element to this flux

being fire; he also extended the teaching that seeming

opposites in fact are manifestations of a common

substrate to good and evil itself.[21]

Eleatic

philosophy

Parmenides

of Elea cast his philosophy against those who

held "it is and is not the same, and all things travel

in opposite directions,"—presumably referring to

Heraclitus and those who followed him.[22]

Whereas the doctrines of the Milesian school, in

suggesting that the substratum could appear in a

variety of different guises, implied that everything

that exists is corpuscular, Parmenides argued that the

first principle of being was One, indivisible, and

unchanging.[23]

Being, he argued, by definition implies eternality,

while only that which is can be thought; a

thing which is, moreover, cannot be more or

less, and so the rarefaction and condensation of the

Milesians is impossible regarding Being; lastly, as

movement requires that something exist apart from the

thing moving (viz. the space into which it moves), the

One or Being cannot move, since this would require

that "space" both exist and not exist.[24]

While this doctrine is at odds with ordinary sensory

experience, where things do indeed change and move,

the Eleatic school followed Parmenides in denying that

sense phenomena revealed the world as it actually was;

instead, the only thing with Being was thought, or the

question of whether something exists or not is one of

whether it can be thought.[25]

In

support of this, Parmenides' pupil Zeno of Elea attempted to

prove that the concept of motion was absurd and

as such motion did not exist. He also attacked the

subsequent development of pluralism, arguing that it

was incompatible with Being.[26]

His arguments are known as Zeno's paradoxes.

Pluralism

and atomism

The power

of Parmenides' logic was such that some subsequent

philosophers abandoned the monism of the Milesians,

Xenophanes, Heraclitus, and Parmenides, where one

thing was the arche, and adopted pluralism, such

as Empedocles and Anaxagoras.[27]

There were, they said, multiple elements which were

not reducible to one another and these were set in

motion by love and strife (as in Empedocles) or by

Mind (as in Anaxagoras). Agreeing with Parmenides that

there is no coming into being or passing away, genesis

or decay, they said that things appear to come into

being and pass away because the elements out of which

they are composed assemble or disassemble while

themselves being unchanging.[28]

Leucippus also proposed an

ontological pluralism with a cosmogony based on two

main elements: the vacuum and atoms. These, by means

of their inherent movement, are crossing the void and

creating the real material bodies. His theories were

not well known by the time of Plato, however, and they were

ultimately incorporated into the work of his student,

Democritus.[29]

Sophistry

Sophistry

arose from the juxtaposition of physis (nature) and nomos

(law). John Burnet posits its origin in the scientific

progress of the previous centuries which suggested

that Being was radically different from what was

experienced by the senses and, if comprehensible at

all, was not comprehensible in terms of order; the

world in which men lived, on the other hand, was one

of law and order, albeit of humankind's own making.[30]

At the same time, nature was constant, while what was

by law differed from one place to another and could be

changed.

The first

man to call himself a sophist, according to Plato, was

Protagoras, whom he presents

as teaching that all virtue is conventional. It was

Protagoras who claimed that "man is the measure of all

things, of the things that are, that they are, and of

the things that are not, that they are not," which

Plato interprets as a radical perspectivism, where some

things seem to be one way for one person (and so

actually are that way) and another way for another

person (and so actually are that way as well);

the conclusion being that one cannot look to nature

for guidance regarding how to live one's life.[31]

Protagoras

and subsequent sophists tended to teach rhetoric as

their primary vocation. Prodicus, Gorgias, Hippias, and Thrasymachus appear in

various dialogues,

sometimes explicitly teaching that while nature

provides no ethical guidance, the guidance that the

laws provide is worthless, or that nature favors those

who act against the laws.

Classical

Greek philosophy

Socrates

Socrates,

born in Athens in the 5th

century BCE, marks a watershed in ancient Greek

philosophy. Athens was a center of learning, with

sophists and philosophers traveling from across Greece

to teach rhetoric, astronomy, cosmology, geometry, and

the like. The great statesman Pericles was closely associated

with this new learning and a friend of Anaxagoras, however, and his

political opponents struck at him by taking advantage

of a conservative reaction against the philosophers;

it became a crime to investigate the things above the

heavens or below the earth, subjects considered

impious. Anaxagoras is said to have been charged and

to have fled into exile when Socrates was about twenty

years of age.[32]

There is a story that Protagoras, too, was forced

to flee and that the Athenians burned his books.[33]

Socrates, however, is the only subject recorded as

charged under this law, convicted, and sentenced to

death in 399 BCE (see Trial of Socrates). In

the version of his defense speech presented

by Plato, he claims that it is the envy he arouses on

account of his being a philosopher that will convict

him.

While

philosophy was an established pursuit prior to

Socrates, Cicero credits him as "the first

who brought philosophy down from the heavens, placed

it in cities, introduced it into families, and obliged

it to examine into life and morals, and good and

evil."[34]

By this account he would be considered the founder of

political philosophy.[35]

The reasons for this turn toward political and ethical

subjects remain the object of much study.[36][37]

The fact

that many conversations involving Socrates (as

recounted by Plato and Xenophon) end without having

reached a firm conclusion, or aporetically,[38]

has stimulated debate over the meaning of the Socratic method.[39]

Socrates is said to have pursued this probing

question-and-answer style of examination on a number

of topics, usually attempting to arrive at a

defensible and attractive definition of a virtue.

While

Socrates' recorded conversations rarely provide a

definite answer to the question under examination,

several maxims or paradoxes for which he has become

known recur. Socrates taught that no one desires what

is bad, and so if anyone does something that truly is

bad, it must be unwillingly or out of ignorance;

consequently, all virtue is knowledge.[40][41]

He frequently remarks on his own ignorance (claiming

that he does not know what courage is, for example). Plato presents him as

distinguishing himself from the common run of mankind

by the fact that, while they know nothing noble and

good, they do not know that they do not know,

whereas Socrates knows and acknowledges that he knows

nothing noble and good.[42]

Numerous

subsequent philosophical movements were inspired by

Socrates or his younger associates. Plato casts

Socrates as the main interlocutor in his dialogues, deriving from them the

basis of Platonism (and by extension, Neoplatonism). Plato's

student Aristotle in turn criticized

and built upon the doctrines he ascribed to Socrates

and Plato, forming the foundation of Aristotelianism. Antisthenes founded the

school that would come to be known as Cynicism and

accused Plato of distorting Socrates' teachings. Zeno of Citium in turn

adapted the ethics of Cynicism to articulate Stoicism. Epicurus studied with Platonic

and Stoic teachers before renouncing all previous

philosophers (including Democritus, on whose atomism

the Epicurean

philosophy relies). The philosophic movements that

were to dominate the intellectual life of the Roman

empire were thus born in this febrile period

following Socrates' activity, and either directly or

indirectly influenced by him. They were also absorbed

by the expanding Muslim world in the 7th through 10th

centuries CE, from which they returned to the West as

foundations of Medieval philosophy

and the Renaissance, as discussed

below.

Plato

Plato was

an Athenian of the

generation after Socrates. Ancient tradition

ascribes thirty-six dialogues and thirteen letters to him,

although of these only twenty-four of the dialogues

are now universally recognized as authentic; most

modern scholars believe that at least twenty-eight

dialogues and two of the letters were in fact written

by Plato, although all of the thirty-six dialogues

have some defenders.[43]

A further nine dialogues are ascribed to Plato but

were considered spurious even in antiquity.[44]

Plato's

dialogues feature Socrates, although not always as the

leader of the conversation. (One dialogue, the Laws,

instead contains an "Athenian Stranger.") Along with Xenophon, Plato is the primary

source of information about Socrates' life and beliefs

and it is not always easy to distinguish between the

two. While the Socrates presented in the dialogues is

often taken to be Plato's mouthpiece, Socrates'

reputation for irony, his caginess regarding his

own opinions in the dialogues, and his occasional

absence from or minor role in the conversation serve

to conceal Plato's doctrines.[45]

Much of what is said about his doctrines is derived

from what Aristotle reports about them.

The

political doctrine ascribed to Plato is derived from

the Republic,

the Laws, and the Statesman.

The first of these contains the suggestion that there

will not be justice in cities unless they are ruled by

philosopher kings;

those responsible for enforcing the laws are compelled

to hold their women, children, and property in common; and the individual is

taught to pursue the common good through noble lies; the Republic

says that such a city is likely impossible, however,

generally assuming that philosophers would refuse to

rule and the people would refuse to compel them to do

so.[46]

Whereas

the Republic is premised on a distinction

between the sort of knowledge possessed by the

philosopher and that possessed by the king or

political man, Socrates explores only the character of

the philosopher; in the Statesman, on the

other hand, a participant referred to as the Eleatic

Stranger discusses the sort of knowledge possessed by

the political man, while Socrates listens quietly.[46]

Although rule by a wise man would be preferable to

rule by law, the wise cannot help but be judged by the

unwise, and so in practice, rule by law is deemed

necessary.

Both the

Republic and the Statesman reveal the

limitations of politics, raising the question of what

political order would be best given those constraints;

that question is addressed in the Laws, a

dialogue that does not take place in Athens and from

which Socrates is absent.[46]

The character of the society described there is

eminently conservative, a corrected or liberalized timocracy on the Spartan or Cretan model or that of

pre-democratic Athens.[46]

Plato's

dialogues also have metaphysical themes, the

most famous of which is his theory

of forms. It holds that non-material abstract

(but substantial) forms (or ideas), and

not the material world of change known to us through

our physical senses, possess the highest and most

fundamental kind of reality.

Plato

often uses long-form analogies

(usually allegories)

to explain his ideas; the most famous is perhaps the Allegory of the Cave.

It likens most humans to people tied up in a cave, who

look only at shadows on the walls and have no other

conception of reality.[47]

If they turned around, they would see what is casting

the shadows (and thereby gain a further dimension to

their reality). If some left the cave, they would see

the outside world illuminated by the sun (representing

the ultimate form of goodness and truth). If these

travelers then re-entered the cave, the people inside

(who are still only familiar with the shadows) would

not be equipped to believe reports of this 'outside

world'.[48]

This story explains the theory of forms with their

different levels of reality, and advances the view

that philosopher-kings are wisest while most humans

are ignorant.[49]

One student of Plato (who would become another of the

most influential philosophers of all time) stressed

the implication that understanding relies upon

first-hand observation:

Aristotle

Aristotle

moved to Athens from his native Stageira in

367 BCE and began to study philosophy (perhaps even

rhetoric, under Isocrates), eventually

enrolling at Plato's Academy.[50]

He left Athens approximately twenty years later to

study botany and zoology, became a tutor of Alexander the Great,

and ultimately returned to Athens a decade later to

establish his own school: the Lyceum.[51]

At least twenty-nine of his treatises have survived,

known as the corpus Aristotelicum,

and address a variety of subjects including logic, physics, optics, metaphysics, ethics, rhetoric, politics, poetry, botany, and zoology.

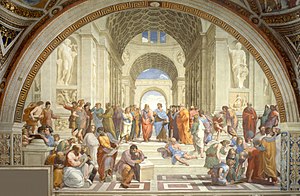

Aristotle

is often portrayed as disagreeing with his teacher

Plato (e.g., in Raphael's School

of Athens). He criticizes the regimes described in Plato's Republic and Laws,[52]

and refers to the theory

of forms as "empty words and poetic metaphors."[53]

He is generally presented as giving greater weight to

empirical observation and practical concerns.

Aristotle's

fame was not great during the Hellenistic period,

when Stoic logic was in vogue, but

later peripatetic

commentators popularized his work, which eventually

contributed heavily to Islamic, Jewish, and medieval

Christian philosophy.[54]

His influence was such that Avicenna referred to him simply

as "the Master"; Maimonides, Alfarabi, Averroes, and Aquinas as

"the Philosopher."

Hellenistic

philosophy

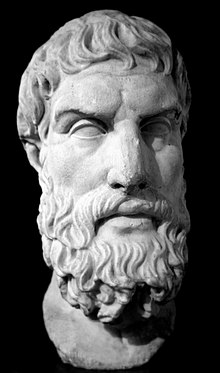

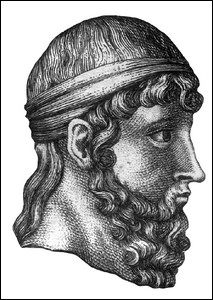

The philosopher Pyrrho from Elis, in an anecdote taken from

Sextus Empiricus'

Pyrrhonic Sketches.

(upper) PIRRHO • HELIENSIS •

PLISTARCHI • FILIVS

translation (from Latin): Phyrrho . Greek .

Son of Plistarchus

(middle) OPORTERE • SAPIENTEM

HANC ILLIVS IMITARI

SECVRITATEM translation (from Latin): It is

right wisdom then that all imitate this

security (Phyrrho pointing at a peaceful pig

munching his food)

(lower) Whoever wants to apply

the real wisdom, shall not mind trepidation

and misery

During

the Hellenistic and Roman periods, many

different schools of thought developed in the Hellenistic

world and then the Greco-Roman

world. There were Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, Syrians and Arabs who

contributed to the development of Hellenistic

philosophy. Elements of Persian philosophy

and Indian philosophy also

had an influence. The most notable schools of

Hellenistic philosophy were:

- Neoplatonism: Plotinus (Egyptian), Ammonius Saccas, Porphyry

(Syrian), Zethos (Arab), Iamblichus

(Syrian), Proclus

- Academic

Skepticism: Arcesilaus, Carneades, Cicero (Roman)

- Pyrrhonian Skepticism: Pyrrho, Sextus Empiricus

- Cynicism: Antisthenes, Diogenes of Sinope,

Crates of Thebes

(taught Zeno of Citium, founder of Stoicism)

- Stoicism: Zeno of Citium, Cleanthes, Chrysippus, Crates of Mallus

(brought Stoicism to Rome c. 170 BCE), Panaetius, Posidonius, Seneca (Roman), Epictetus (Greek/Roman), Marcus Aurelius (Roman)

- Epicureanism: Epicurus (Greek) and Lucretius (Roman)

- Eclecticism: Cicero (Roman)

The

spread of Christianity throughout the

Roman world, followed by the spread of Islam, ushered

in the end of Hellenistic philosophy and the

beginnings of Medieval philosophy,

which was dominated by the three Abrahamic

traditions: Jewish philosophy, Christian philosophy,

and early Islamic

philosophy.

Transmission

of Greek philosophy under Islam

During

the Middle Ages, Greek ideas

were largely forgotten in Western Europe (where,

between the fall of

Rome and the East-West

Schism, literacy in Greek had declined

sharply). Not long after the first major expansion of

Islam, however, the Abbasid caliphs

authorized the gathering of Greek manuscripts and

hired translators to increase their prestige. Islamic philosophers

such as Al-Kindi (Alkindus), Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn

Sina (Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) reinterpreted these

works, and during the High Middle Ages Greek

philosophy re-entered the West through translations

from Arabic to Latin. The re-introduction of

these philosophies, accompanied by the new Arabic

commentaries, had a great influence on Medieval philosophers

such as Thomas Aquinas.

See also

Notes

- Alfred

North Whitehead, Process and Reality, Part

II, Chap. I, Sect. I

- Griffin, Jasper; Boardman,

John; Murray, Oswyn (2001). The Oxford

history of Greece and the Hellenistic world.

Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press.

p. 140. ISBN0-19-280137-6.

- Greg

Whitlock, preface to The Pre-Platonic

Philosophers, by Friedrich Nietzsche

(Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001),

xiv–xvi.

- Greg Whitlock, preface to The

Pre-Platonic Philosophers, by Friedrich

Nietzsche (Urbana: University of Illinois Press,

2001), xiii–xix.

- John

Burnet, Greek Philosophy: Thales to Plato,

3rd ed. (London: A & C Black Ltd., 1920),

3–16. Scanned

version from Internet Archive

- Aristotle, Metaphysics

Alpha, 983b18.

- Aristotle,

Metaphysics Alpha, 983 b6 8–11.

- Burnet, Greek

Philosophy, 3–4, 18.

- Burnet, Greek

Philosophy, 18–20; Herodotus, Histories,

I.74.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 22–24.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 21.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 27.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 35.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 35; Diels-Kranz, Die

Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, Xenophanes frr.

15-16.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 36.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 33, 36.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 37–38.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 38–39.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 40–49.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 57.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 57–63.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 64.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 66–67.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 68.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 67.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 82.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 69.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 70.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 94.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 105–10.

- Burnet,

Greek Philosophy, 113–17.

- Debra

Nails, The People of Plato (Indianapolis:

Hackett, 2002), 24.

- Nails,

People of Plato, 256.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, Tusculan Disputations,

V 10–11 (or V IV).

- Leo

Strauss, Natural Right and History

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), 120.

- Seth

Benardete, The Argument of the Action

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000),

277–96.

- Laurence

Lampert, How Philosophy Became Socratic

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010).

- Cf.

Plato, Republic

336c & 337a, Theaetetus

150c, Apology of Socrates

23a; Xenophon, Memorabilia

4.4.9; Aristotle, Sophistical

Refutations 183b7.

- W. K. C. Guthrie, The

Greek Philosophers (London: Methuen, 1950),

73–75.

- Terence Irwin, The

Development of Ethics, vol. 1 (Oxford:

Oxford University Press 2007), 14

- Gerasimos

Santas, "The Socratic Paradoxes", Philosophical

Review 73 (1964): 147–64, 147.

- Apology of Socrates

21d.

- John

M. Cooper, ed., Complete Works, by Plato

(Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997), v–vi, viii–xii,

1634–35.

- Cooper,

ed., Complete Works, by Plato, v–vi,

viii–xii.

- Leo Strauss, The

City and Man (Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1964), 50–51.

- Leo Strauss, "Plato", in History

of Political Philosophy, ed. Leo Strauss and

Joseph Cropsey, 3rd ed. (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press 1987): 33–89.

- "Plato

- Allegory of the cave" (PDF). classicalastrologer.files.wordpress.com.

- "Allegory

of the Cave". washington.edu.

- Garth Kemerling. "Plato:

The Republic 5-10". philosophypages.com.

- Carnes Lord, Introduction

to The Politics, by Aristotle (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1984): 1–29.

- Bertrand Russell, A

History of Western Philosophy (New York:

Simon & Schuster, 1972).

- Aristotle,

Politics,

bk. 2, ch. 1–6.

- Aristotle,

Metaphysics,

991a20–22.

- Robin

Smith, "Aristotle's

Logic,"

Stsmgotd Encyclopedia of Philosophy

(2007).

References

- Bakalis,

Nikolaos (2005). Handbook of Greek Philosophy:

From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments,

Trafford Publishing ISBN

1-4120-4843-5

- John

Burnet, Early

Greek Philosophy, 1930.

- William

Keith Chambers Guthrie, A History of Greek

Philosophy: Volume 1, The Earlier Presocratics

and the Pythagoreans, 1962.

- Kierkegaard, Søren,

On the Concept of Irony

with Continual Reference to Socrates,

1841.

- Martin Litchfield

West, Early Greek Philosophy and the

Orient, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1971.

- Martin

Litchfield West, The East Face of Helicon:

West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth,

Oxford [England] ; New York: Clarendon Press,

1997.

- Charles Freeman (1996). Egypt,

Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press.

- A.A.

Long. Hellenistic Philosophy. University

of California, 1992. (2nd Ed.)

- Artur

Rodziewicz, IDEA AND FORM. ΙΔΕΑ ΚΑΙ ΕΙΔΟΣ. On

the Foundations of the Philosophy of Plato and

the Presocratics (IDEA I FORMA. ΙΔΕΑ ΚΑΙ ΕΙΔΟΣ.

O fundamentach filozofii Platona i

presokratyków) Wroclaw, 2012.

- Baird, Forrest E.; Walter

Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida.

Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice

Hall. ISBN 0-13-158591-6.

Further

reading

- Nightingale,

Andrea Wilson, Spectacles

of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy:

Theoria in Its Cultural Context,

Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN

0-521-83825-8

- Loudovikos, Nikolaos,

Protopresbyter, Theological History of the

Ancient Hellenic Philosophy – Presocratics,

Socrates, Plato (in Greek), Pournaras

Publishing, Athens, 2003, ISBN

960-242-296-3

- The

Hemlock Cup: Socrates, Athens and the Search for

the Good Life, by Bettany Hughes (2010) ISBN

0-224-07178-5

- Luchte,

James, Early Greek Thought: Before the Dawn,

in series, Bloomsbury Studies in Ancient

Philosophy, Bloomsbury Publishing, London,

2011. ISBN

978-0567353313

External

links

|

Ancient Greek philosophical

concepts

|

|

|

|

-----------------

3. Socrates

Socrates (;[2]

Greek: Σωκράτης

[sɔːkrátɛːs],

Sōkrátēs; 470/469 – 399 BC)[1]

was a classical Greek (Athenian) philosopher credited as one of

the founders of Western philosophy. He

is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the

accounts of classical writers, especially the writings

of his students Plato and Xenophon and the plays of his

contemporary Aristophanes. Plato's dialogues are among the most

comprehensive accounts of Socrates to survive from

antiquity, though it is unclear the degree to which

Socrates himself is "hidden behind his 'best disciple',

Plato".[3]

Through

his portrayal in Plato's dialogues, Socrates has

become renowned for his contribution to the field of ethics, and it is this Platonic

Socrates who lends his name to the concepts of Socratic irony and the Socratic method, or elenchus.

The latter remains a commonly used tool in a wide

range of discussions, and is a type of pedagogy in which a series of

questions is asked not only to draw individual

answers, but also to encourage fundamental insight

into the issue at hand. Plato's Socrates also made

important and lasting contributions to the field of epistemology, and his

ideologies and approach have proven a strong

foundation for much Western philosophy that has

followed.

The

Socratic problem

Nothing

written by Socrates remains extant. As a result, all

first-hand information about him and his philosophies

depends upon secondary sources. Furthermore, close

comparison between the contents of these sources reveals

contradictions, thus creating concerns about the possibility

of knowing in-depth the real Socrates. This issue is

known as the Socratic problem,[4]

or the Socratic question.[5][6]

To

understand Socrates and his thought, one must turn

primarily to the works of Plato, whose dialogues are thought

the most informative source about Socrates' life and

philosophy,[7]

and also Xenophon.[8]

These writings are the Sokratikoi logoi, or Socratic dialogues,

which consist of reports of conversations apparently

involving Socrates.[9][10]

As for

discovering the real-life Socrates, the difficulty is

that ancient sources are mostly philosophical or

dramatic texts, apart from Xenophon. There are no

straightforward histories, contemporary with Socrates,

that dealt with his own time and place. A corollary of

this is that sources that do mention Socrates do not

necessarily claim to be historically accurate, and are

often partisan. For instance, those who prosecuted and

convicted Socrates have left no testament. Historians

therefore face the challenge of reconciling the various

evidence from the extant texts in order to attempt an

accurate and consistent account of Socrates' life and

work. The result of such an effort is not necessarily

realistic, even if consistent.

Amid all

the disagreement resulting from differences within

sources, two factors emerge from all sources pertaining

to Socrates. It would seem, therefore, that he was ugly,

and that Socrates had a brilliant intellect.[11][12]

Socrates

as a figure

The

character of Socrates as exhibited in Apology, Crito, Phaedo and Symposium concurs

with other sources to an extent to which it seems

possible to rely on the Platonic Socrates, as

demonstrated in the dialogues, as a representation of

the actual Socrates as he lived in history.[13]

At the same time, however, many scholars believe that in

some works, Plato, being a literary artist, pushed his

avowedly brightened-up version of "Socrates" far beyond

anything the historical Socrates was likely to have done

or said. Also, Xenophon, being an historian, is a more

reliable witness to the historical Socrates. It is a

matter of much debate over which Socrates it is whom

Plato is describing at any given point—the historical

figure, or Plato's fictionalization. As British

philosopher Martin Cohen

has put it, "Plato, the idealist, offers an idol, a

master figure, for philosophy. A Saint, a prophet of

'the Sun-God', a teacher condemned for his teachings as

a heretic."[14][15]

It is also

clear from other writings and historical artefacts, that

Socrates was not simply a character, nor an invention,

of Plato. The testimony of Xenophon and Aristotle,

alongside some of Aristophanes' work (especially The Clouds), is useful in

fleshing out a perception of Socrates beyond Plato's

work.

Socrates

as a philosopher

The problem

with discerning Socrates' philosophical views stems from

the perception of contradictions in statements made by

the Socrates in the different dialogues of

Plato. These contradictions produce doubt as to the

actual philosophical doctrines of Socrates, within his

milieu and as recorded by other individuals.[16]

Aristotle, in his Magna Moralia, refers to

Socrates in words which make it patent that the doctrine

virtue is knowledge was held by Socrates. Within

the Metaphysics, he states Socrates was occupied

with the search for moral virtues, being the ' first

to search for universal definitions for them '.[17]

The problem

of understanding Socrates as a philosopher is shown in

the following: In Xenophon's Symposium,

Socrates is reported as saying he devotes himself only

to what he regards as the most important art or

occupation, that of discussing philosophy. However, in The

Clouds, Aristophanes portrays Socrates as

accepting payment for teaching and running a sophist school with Chaerephon. Also, in Plato's Apology and Symposium, as well

as in Xenophon's accounts, Socrates explicitly denies

accepting payment for teaching. More specifically, in

the Apology, Socrates cites his poverty as proof

that he is not a teacher.

Two

fragments are extant of the writings by Timon of Phlius pertaining

to Socrates,[18]

although Timon is known to have written to ridicule and

lampoon philosophy.[19][20]

Biography

Carnelian gem imprint

representing Socrates, Rome, 1st century BC-1st

century AD.

Details

about the life of Socrates can be derived from three

contemporary sources: the dialogues of Plato and Xenophon

(both devotees of Socrates), and the plays of Aristophanes. He has been

depicted by some scholars, including Eric

Havelock and Walter Ong,

as a champion of oral modes of communication,

standing against the haphazard diffusion of writing.[21]

In

Aristophanes' play The Clouds, Socrates is

made into a clown of sorts, particularly inclined toward

sophistry,

who teaches his students how to bamboozle their way out

of debt. However, since most of Aristophanes' works

function as parodies, it is presumed that his

characterization in this play was also not literal.[22]

Early life

Socrates

was born in Alopeke, and belonged to the tribe Antiochis. His

father was Sophroniscus, a sculptor, or

stonemason.[23][24][25]

His mother was a midwife named Phaenarete.[26]

Socrates married Xanthippe, who is especially

remembered for having an undesirable temperament.[27]

She bore for him three sons,[28]

Lamprocles, Sophroniscus and Menexenus. His friend Crito of Alopece

criticized him for abandoning them when he refused to

try to escape before his execution.[29]

Socrates

first worked as a stonemason, and there was a tradition

in antiquity, not credited by modern scholarship, that

Socrates crafted the statues of the Three Graces, which

stood near the Acropolis until the 2nd century AD.[30]

Xenophon

reports that because youths were not allowed to enter

the Agora, they used to gather in

workshops surrounding it.[31]

Socrates frequented these shops in order to converse

with the merchants. Most notable among them was Simon the Shoemaker.[32]

Military

service

For a time,

Socrates fulfilled the role of hoplite, participating in the Peloponnesian

war—a conflict which stretched intermittently over

a period spanning 431 to 404 B.C.[33]

Several of Plato's dialogues refer to Socrates' military

service.

In the

monologue of the Apology, Socrates states he was

active for Athens in the battles of Amphipolis, Delium, and Potidaea.[34]

In the Symposium, Alcibiades describes Socrates'

valour in the battles of Potidaea and Delium, recounting

how Socrates saved his life in the former battle

(219e-221b). Socrates' exceptional service at Delium is

also mentioned in the Laches by the

General after whom the dialogue is named (181b). In the

Apology, Socrates compares his military service

to his courtroom troubles, and says anyone on the jury

who thinks he ought to retreat from philosophy must also

think soldiers should retreat when it seems likely that

they will be killed in battle.[35]

Epistates

at the trial of the six commanders

During 406,

he participated as a member of the Boule.[36]

His tribe the Antiochis held the Prytany on the

day it was debated what fate should befall the generals

of the Battle of Arginusae,

who abandoned the slain and the survivors of foundered

ships to pursue the defeated Spartan navy.[24][37][38]

According

to Xenophon, Socrates was the Epistates for the debate,[39]

but Delebecque and Hatzfeld think this is an

embellishment, because Xenophon composed the information

after Socrates' death [40]

The

generals were seen by some to have failed to uphold the

most basic of duties, and the people decided upon

capital punishment. However, when the prytany responded

by refusing to vote on the issue, the people reacted

with threats of death directed at the prytany itself.

They relented, at which point Socrates alone as

epistates blocked the vote, which had been proposed by Callixeinus.[41][42]

The reason he gave was that "in no case would he act

except in accordance with the law".[43]

The outcome

of the trial was ultimately judged to be a miscarriage

of justice, or illegal, but, actually, Socrates'

decision had no support from written statutory law,

instead being reliant on favouring a continuation of

less strict and less formal nomos law.[42][44][45]

The arrest

of Leon

Plato's Apology, parts 32c to 32d,

describes how Socrates and four others were summoned to

the Tholos,

and told by representatives of the oligarchy of the Thirty

(the oligarchy began ruling in 404 B.C.) to go to

Salamis, and from there, to return to them with Leon the Salaminian. He

was to be brought back to be subsequently executed.

However, Socrates returned home and did not go to

Salamis as he was expected to.[46][47]

Trial and death

Socrates

lived during the time of the transition from the height

of the Athenian hegemony to its decline with the

defeat by Sparta and its allies in the Peloponnesian War. At a

time when Athens sought to

stabilize and recover from its humiliating defeat, the

Athenian public may have been entertaining doubts about

democracy as an efficient form of government. Socrates

appears to have been a critic of democracy,[48]

and some scholars interpret his trial as an expression

of political infighting.[49]

Claiming

loyalty to his city, Socrates clashed with the current

course of Athenian politics and society.[50]

He praises Sparta, archrival to Athens, directly and

indirectly in various dialogues. One of Socrates'

purported offenses to the city was his position as a

social and moral critic. Rather than upholding a status

quo and accepting the development of what he perceived

as immorality within his region, Socrates questioned the

collective notion of "might makes right" that he felt

was common in Greece during this period. Plato refers to

Socrates as the "gadfly" of the state (as the

gadfly stings the horse into action, so Socrates stung