Cola di Rienzi

Sometimes

a man just goes too far, exceeds his mandates and his skills, gets a

bit

megalomaniacal, and ends up paying the price. As you climb

Michelangelo's

ramp to the Campidoglio, tale a glance to the left at the statue about

half way up. It's in the grassy space between the ramp and the steeper

stairway to S. Maria in Aracoeli Church. The small monument, which is

near

the place where fate caught up to Cola di Rienzi, doesn't deserve much

more than a glance -- it's neither distinguished nor old (put up by

Mussolini,

a fan and emulator, in all ways, of Rienzi). Few people who have

climbed

the ramp have even noticed that it is there.

Nicholas

Rienzo Gabrini, called

Cola di Rienzi, was the son of an innkeeper and a laundry woman.

Despite

poverty, they managed to give Cola a classical education, which, Edward

Gibbon says (in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire), was

"the

cause of his glory and untimely end." Rienzi was a great fan of the

classical

orators and authors and studied "with indefatigable diligence the

manuscripts

and marbles of antiquity." He emulated the speaking style of the

classical

greats, and his rhetorical skills were recognized in foreign diplomatic

assignments, in a meeting with Pope Clement VI (in Avignon), and in

friendship

with the Petrarch, the most famous historian and political theorist of

his day. Rienzi's embarrassing poverty was relieved by employment as

the

Pope's notary in Rome, and the salary was large enough -- five gold

Florins

a day -- that he could write and speechify at his leisure.

Most

of his speeches, delivered

in public gatherings on the Campidoglio, emphasized the corruption of

the

nobles, the needs of the common people, and especially his own honesty

and integrity -- always as a representative of the values of ancient

Republican

Rome. This found a ready audience, because every evil deed and

intention

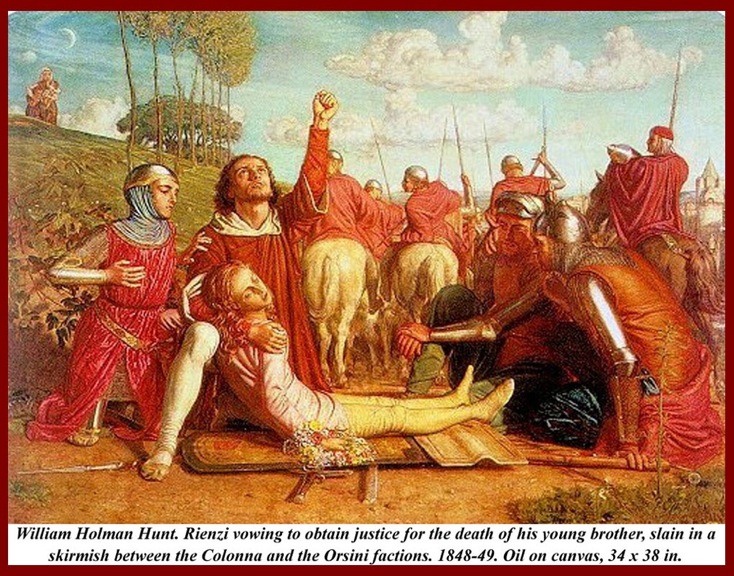

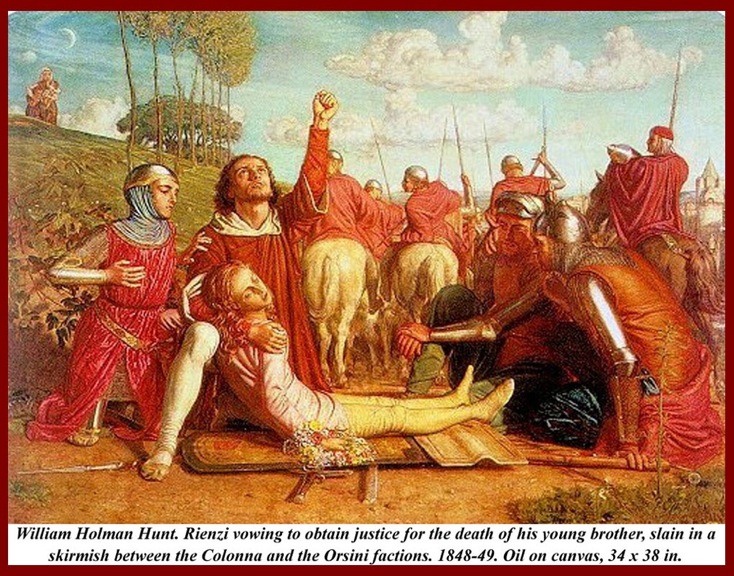

he blamed on the nobility was undoubtedly true. The public murder of

Rienzi's

own brother by a nobleman had gone unpunished, nor was such an

occurrence

uncommon. Rape of citizens' wives and daughters by noble sons was also

a common and justified complaint.

Rienzi

became a popular public speaker,

pamphleteer, letter writer, and poster artist. Everything had the same

theme, and the audiences were enthusiastic. Even the nobles attended

his

public assemblies, taking them as an opportunity to exchange amongst

themselves

wry comments and criticisms. He was invited to the Colonna palace to

amuse

the assembled nobility with his threats and predictions.

And

then, on May 20, 1347, he called

a "secret" assembly -- the notice was posted on the church doors -- on

the Aventine. There he told the commons that he had the support of the

Pope, who also wanted to take the nobles down a notch or two. The next

night, he (in full armor) and his volunteers, marched forth from the

Church

of Sant'Angelo to the Campidoglio with the Bishop of Orvieto, a Papal

representative,

and declared the reestablishment of the Republic. The moment was well

chosen:

Stephan Colonna, the leader of the nobles, was out of town.

Colonna

quickly returned to Rome

and threatened to throw Rienzi out of the windows of the Capitol.

Rienzi's

people sounded the church bells and the mob assembled to protect him.

The

nobility fled in disarray. The mob wanted to proclaim Rienzi Consul,

King,

or Emperor, but he chose the more modest title of Tribune -- secure in

the knowledge that the commons did not know that a Tribune had no

legislative

or executive powers.

While

it lasted, things were good.

There was law and order and everyone -- even the highest of the

nobility

and clergy -- had to answer for what they did. Rienzi ruled by decree,

and many of his laws were liberal and actually passed power back to the

people, but his inexperience quickly became obvious. Few cared: the

streets

were safe, there were no robbers in the forests, and, if there had been

trains, they would have run on time. Rienzi became a celebrity at home

and abroad. He corresponded with philosophers and kings, wrote

political

theory and received foreign visitors and emmisaries. Petrarch, who had

been the darling of the nobility and the Papacy, now became a public

sympathizer

with and advisor to Rienzi.

Eventually

things started to fall

apart, and Rienzi could only keep things going by raiding the municipal

and Papal treasuries. This cost him the Pope's support, and the

nobility,

of course, had always hated him. And the pressure just got to be too

great

for Cola. As Gibbon says, "his virtues were insensibly tinctured with

the

adjacent vices; justice with cruelty, liberality with profusion, and

the

desire of fame with puerile and ostentatious vanity". He took for

himself

ostentatious titles, fur-lined satin and velvet robes, a massive

scepter,

a white steed, trumpets, drums, parades and processions, and a

praetorian

guard. Gold and silver coins were scattered in his wake. He had himself

crowned with seven successive crowns, received the knighthood in the

"Order

of the Holy Ghost" and, what was most scandalous to the people, bathed

in the porphyry basin in which Constantine was reputedly cured of his

leprosy

by Pope Sylvester. The bath, even greater scandal, was in the

baptistery

of St. John Lateran. As a final straw, he publicly commanded the Pope

(Clement,

still in Avignon) and various royalty, electors, and nobility to come

to

Rome to surrender to him the various parts of the Roman Empire that

they

had usurped. Meanwhile, he was indulging the princely and Papal vice of

nepotism -- all the Rienzis soon had good jobs.

The

nobles, after humiliation, mock

trials and last minute reprieves from execution, finally organized

themselves

into a rebellion. Their first attempt to retake the city resulted in

their

ignominious defeat, and many important nobles were slain by the citizen

defenders of Rome. Rienzi took this as a validation of his megalomania.

But when he tried to institute a new tax it was widely opposed in the

city

-- the people were tired of paying for his excesses. The Pope was also

disenchanted, and after fruitless negotiations, the Cardinal Legate

(the

Pope's Ambassador) excommunicated Rienzi and accused him of rebellion,

sacrilege, and heresy -- the big three in Papal condemnations.

The

Nobles were still cowed after

their early defeat, but one desparate character, the Count of Peperino

(who had just been released from prison through the efforts of Rienzi's

friend Plutarch) infiltrated Rome with one hundred and fifty soldiers.

They took over the old Colonna palaces quite easily, and, when the big

bell on the Capitol rang the alarm, nobody came to defend poor Cola.

Cola

ran for cover but was caught and imprisoned in the Castel Sant'Angelo,

and the nobles retook the city.

The

nobles also had learned nothing

from their experience and quickly reestablished their reign of terror

in

Rome and the countryside. Seven years later, Rienzi escaped from his

formidable

prison -- there must have been inside help -- and began to wander

Europe

showing up in the most unexpected places, including, finally, the court

of Emperor Charles IV, who immediately had him arrested and transferred

to Papal custody in Avignon -- he was confined but comfortable. The

succeeding

Pope, Innocent IV sent him back to Rome, either because he believed in

Rienzi's message, or, according to revisionists, because he wanted to

cause

mischief.

Rienzi

was received again in Rome

in 1354 as a redeemer -- the mob turned out and proclaimed that his

laws

and decrees were reinstated. The noble were forced to flee again.

Rienzi's

second reign lasted four months. Reinzi was seized in a bloody melee

organized

by the Barons and displayed on the balcony at the Capitol. After about

an hour of indecision, with the mob looking on, the first dagger blow

hit

him in the chest, probably killing him immediately. Numerous other

blows

followed and finally, according to Gibbon, his body "was abandoned to

the

dogs...and to the flames".

Internet

links:

Gibbon

-- Decline and Fall:

http://www.ccel.org/g/gibbon/decline/volume2/chap70.htm

Catholic

Encyclopedia version of

the tale:

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13052c.htm

Richard

Wagner's opera, Rienzi (in

German):

http://www.physcip.uni-stuttgart.de/phy11733/wagner/rienzi.html

Edward

Bulwer-Lytton's famous 1835

novelization:

http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/1396

Warning! Bulwer-Lytton, who also

wrote The Last Days of Pompeii, is well known for his ponderous

writing style. Much of his modern fame rests on the fact that he

started

another of his novels, Paul Clifford, (1830) with the famous

sentence,

"It was a dark and stormy night." See http://www.bulwer-lytton.com/

-----------------------

updated December 4, 2009