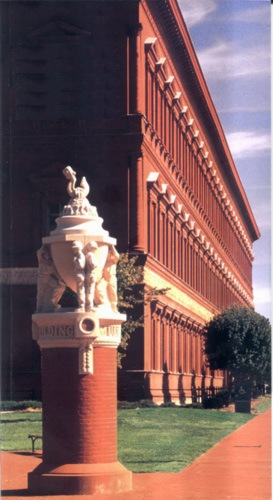

Mystery Building -- Where and what is it?

Here are some hints: Its exterior is modeled after the younger Antonio da Sangallo's Palazzo Farnese in Rome (built 1530-1548 AD), but its brickwork is uniformly red rather than the predominantly tan bricks of the Farnese. The details and proportions (but not the decorations) of the cornice atop the exterior walls are copied from the Cornice Michelangelo added to the Farnese (about 1550)

The 1200-foot frieze that circles the whole building above the ground floor windows, like parts of the frieze of its Athenian Parthenon model, is a parade of warriors.

The interior courtyard emulates the cortile of the Cancelleria, a near neighbor of the Farnese (attributed to Donato Bramante and built between 1489 and 1511).

The architect of our building consulted the 1592 printing of Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola's "Regola delli cinque ordini d'architettura" (first edition was in 1573) to determine the correct proportions of the cortile's Ionic and Doric columns and of the eight massive Corinthian columns that support a roof over the courtyard.

Our architect proudly wrote that his huge Corinthians, 75 feet high and 8 feet in diameter, were even larger than their models in Diocletian's Roman baths, which Michelangelo had rebuilt as the Church of Santa Maria degli Angeli. He also ensured that the columns were larger than those in the famous Temple of Jupiter in Baalbeck in The Lebanon.Enough clues. The mystery site is also in Washington. It was originally designed as an office building to house the Pension Bureau, which was responsible for the support of military casualties and the dependents of those who died in military service (a predecessor organization if the Veterans Administration and the Department of Veterans Affairs). The greater demands on the Pension Bureau after the Civil War necessitated this much larger and centralized location.Our building is the biggest building ever built of load-bearing brick masonry, using more than fifteen-and-a-half million bricks. Those big columns in the courtyard, also made of brick, each used more than 70,000 bricks.

Unlike its Italian Renaissance and Classical Roman and Greek models, this building's construction was thoroughly documented and photographed. (The photography of the construction is a big hint -- that puts it in the last 150 or so years).

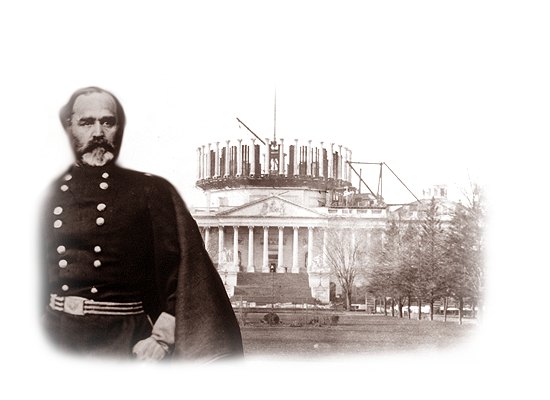

The building's architect, who was also its construction maestro (in modern terms, its engineer), had previously designed a bridge that had the longest masonry arch ever built (220 feet) until the 20th century, and he was responsible for the layout of the wings and the design of the Dome of the US Capitol Building in Washington DC. He graduated fifth in the 1836 class at West Point and was the Quartermaster General of the Union forces during the American Civil War, a position that made him "second only to Grant" in the Union victory.

A Postcard view of the front of the MuseumThe architect/engineer (a rare combination even in those days) was General Montgomery Cunningham Meigs. It is thought by some architectural historians that Meigs hoped to move Washington DC architecture in a Roman Renaissance direction to celebrate a post-Civil War American Renaissance. A main selling point for the Renaissance style, as far as Meigs was concerned, was the healthful availability of light and fresh air that Renaissance courtyards afforded: although Meigs roofed the courtyard, to provide a central "Grand Hall", he ringed it with levels of operable clerestory windows and put large architectural skylights in the side bays of the grand hall and above the top-floor offices.

Meigs was also responsible for the final design and erection of the US Capitol dome.But the depression of the 1890s intervened, and Meigs' Washington version of the Roman Renaissance style faltered. Later monumental structures in the city reverted to (neo)classical Palladian or went off in other directions like the novel Pentagon, the grotesque neo-Stalinist State Department (now called the Truman Building), and I.M. Pei's exciting East Building at the National Gallery of Art.

The Pension Bureau occupied the still uncompleted "Pension Building" in 1885, only three years after construction began. That same year, Grover Cleveland's first inaugural ball was held in the Grand Hall. Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft held six more inaugurations in the Hall, but Woodrow Wilson decided not to hold a ball in 1913, and the whole ball tradition died out until after World War 2. By the time the tradition had revived, the building had passed to other agencies and the Grand Hall was partitioned into cubicles that prevented its use for public functions. It wasnít until 1973, after the cubicles were finally removed, that Richard Nixon held one of his three simultaneous balls in the hall. Since then, It has been the site of an inaugural ball every four years with succeeding Presidents.

Just how big is the hall? At 116 feet by 316 feet, it would almost be big enough to hold an American football field -- the big columns would be a hazard, but the 159-foot height would be ample for even the highest kick. Rooms around both levels of the cortile are typically 38 feet square and are used now as exhibit spaces. A third level of similarly sized rooms were originally used to store hard copy pension records (the only kind they had) but are now used as offices. It is those offices that now have the wonderful skylight lanterns. There are arched entrances at the center of each of the sides of the hall, and next to them are broad brick staircases -- with shallow grades like those in Renaissance palazzi -- connecting the ground and second level. Meigs said that the shallow grades were suitable for the disabled veterans who frequented the building and who also comprised much of the Pension Bureau staff.

The building barely escaped demolition several times, and in 1934 a proposal to cover it with marble and convert it into yet another Washington neoclassical demonstration was narrowly avoided. Its last government tenant was the Superior Court of the District of Columbia (1972-78) while the Court's own new quarters were under construction. In 1975 a "Committee for the Museum of the Building Arts" was formed with the idea of restoring the old Pension Building to its original splendor. Congress officially set up the National Building Museum, which now occupies the site, in 1980 as a public-private partnership: the Federal Government provides the building and a private non-profit organization, funded by donations and memberships, runs the Museum. Only a few minor projects remain for complete restoration.

The National Building Museum is open to the public daily (Monday through Saturday - 10AM-5PM, Sundays - 11AM-5PM) except Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years Day. It is also closed to the public for exceptional special occasions -- mainly inaugural balls. Details of Location, hours, facilities, and temporary and semi-permanent exhibitions are at the museum's Internet site at http://www.nbm.org/Info/visit.html. The site also, of course, has some good pictures of the Museum.

The Museum is wheelchair accessible, with ramps and elevators wherever needed. Meigs had included elevator shafts in his original construction plan, for the convenience of disabled veterans, but money wasn't available to install the elevators until long after the Pension Bureau had given up the site. New elevators were installed in the same shafts in the 1990s. Multiple modern clean restrooms are on every floor. There is a small snack bar (sandwiches, soups, salads, baked goods, beverages) with tables on the floor of the Grand Hall and benches around the restored fountain at its center. Guided tours of the building are offered daily. Exhibition guides and brochures are available in English only, signage also only in English. On-street parking around the Museum is scarce, especially on work days. You can always park at the MCI Center sports complex for $12, but it's a lot cheaper to take the Metro subway, which has a Red Line station at Judiciary Square.

The Museum store had a good collection of books on architecture, focused mostly on Washington and the US, but there were also several books on Italian and Roman architecture and construction that I had never seen before. The store also has a selection of architecture/building-related toys for kids and adults and only a very few bits of the tacky tourist gimcrackery that is so common around the city. More importantly, it is the only place where I have ever found the National Building Museum's history of the building itself, "Building as Landmark," an amply illustrated 64-page booklet ($8), from which much of the information in this article was gleaned.

As mentioned above, the Museum has its own extensive new Internet site at http://www.nbm.org/Info/visit.html.

Pictures of the Palazzo Farnese are at http://www.romeartlover.it/Vasi73.htm, and Cancelleria Cortile pictures are at http://www2.siba.fi/~kkoskim/rooma/pages/PCANCELL.HTM.

The Parthenon Frieze is at http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/CGPrograms/Catalogue/Script/ParthenonFrieze.html, and a sample of the National Building Museum Frieze is at http://www.goethe.de/ins/us/was/pro/vtour/dc1/C2/27/en_tmb_1.htm.

A review of a recent book concerning Meigs' contributions to Washington DC architecture is at http://www.ohiou.edu/oupress/montgomerymeigsreview.htm.

Amazon has the book at http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/082141397X/104-9024221-2662334.

The Caspar Buberl Frieze

Length 1,200 feet

Height 3 feet

White Terra Cotta(From http://away.com/primedia/arts_arch/pension_building.html)

From the beginning, Meigs envisioned encircling his building with a dramatic frieze, like the one on the Parthenon. But he didn't want classical or allegorical figures for his frieze. He wanted realism--men and boys who looked just like the ones he was so proud of, like his own son--and he wanted every boot, wagon wheel, crutch, saber, saddle and sidearm he'd supplied as quartermaster to be visible.Meigs chose terra cotta as the medium for the frieze because it was inexpensive, durable and could be worked to a high degree of detail. To sculpt it he chose Bohemian-born New York artist Caspar Buberl, with whom he had worked on the Smithsonian Institution's Arts and Industries Building. Although Meigs and Buberl sparred over every detail, they eventually agreed upon six themes (infantry, cavalry, artillery, navy, medicine and, of course, quartermaster) to be repeated in various sequences around the building's 1,200-foot perimeter.

Not until the entire building was completed did the full effect of Buberl's frieze dawn on Meigs. The high relief, the earthy, raw quality of the clay, the realism of the figures, the palpable sense of purpose--all created exactly the impression Meigs wanted. No one man among the approximately 1,355 figures stood out. Together they move forward, marching, rowing, galloping, and limping along with an inexorable cadence that is difficult to resist.

Building Facts

Montgomery Meigs wanted his building to be superlative in every way. It is the largest all-brick building in the world -- other "brick" structures that are larger are actually built around steel of concrete cores (like, for example, the Colosseum in Rome). He used locally made bricks -- 15,500,000 of them, give or take a few and not counting the thousands of specially made decorative bricks and tiles that he used to ornament the Museum. To ensure that his eight huge internal columns were the biggest ever, he measured those at the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Rome (the Baths of Diocletion remade into a chuch by Michelangelo) and those in the Jupiter Temple in Baalbeck in Lebanon, which were reputed to be the largest structural columns in the world. He made his a bit bigger and made them, of course, of brick.

P.S.: Ghosts? Like many old buildings, this one has its share of putative resident spirits. If you see a wispy figure limping around the upper cortile level, that would be former pension commissioner James Tanner, who lost both feet at the Second Battle of Bull Run. There are others, but my favorite is the ghost of Buffalo Bill (William F. Cody). Cody went to at least two inauguration balls in the Grand Hall, one for Harrison and Teddy Roosevelt's second, and at the Roosevelt Ball he was said to have remarked that he would like to haunt the place. Some folks say he does.