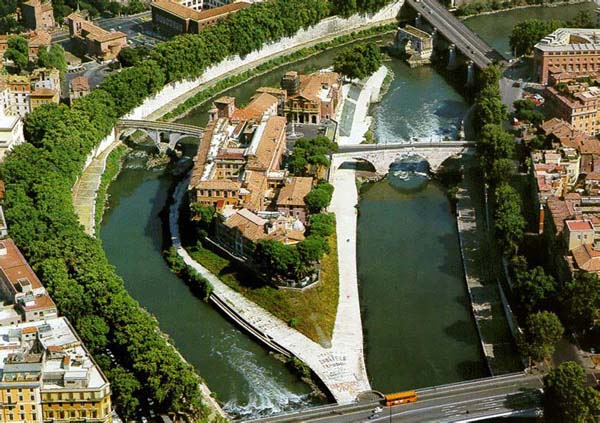

Above, a recent aerial photograph of Rome's Tiber Island

Above, a recent aerial photograph of Rome's Tiber

Island

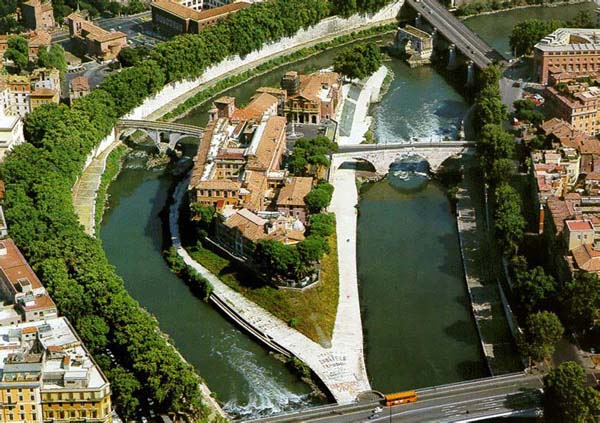

Above, fanciful reconstruction of how the island

was thought to have looked in ancient times,

from the Pirro Ligorio Map of Ancient Rome,

1561

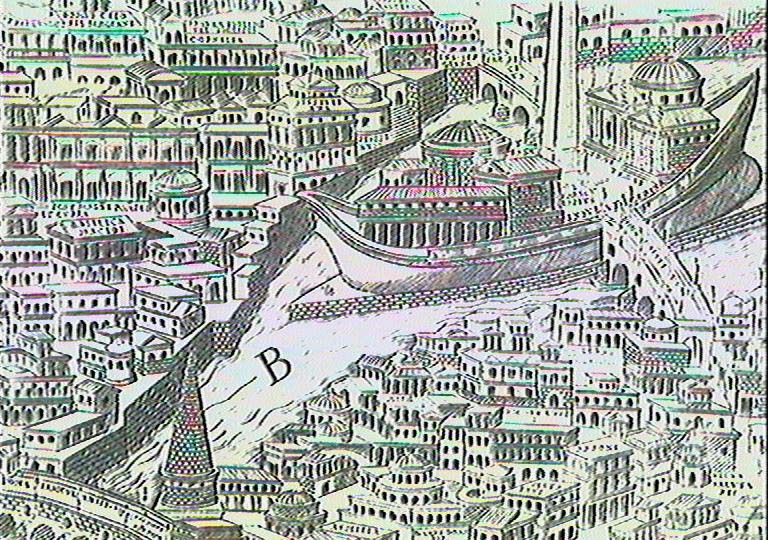

The Island was, in fact, decorated to look like a boat in ancient times, with high structures on each end and an obelisk for a mast in the center. The only part of the decoration that remains is a barely visible Rostrum(ramming prow) carved in travertine on the upstream end of the island, pictured below.

You can explore Rome's Tiber Island in a few hours, and, since it is the only island that lies within Rome's boundaries, you can then say that you have done all the islands in Rome. There were once other islands in the swampy area of the Campus Martius, but already in ancient Roman times the swamp was mostly drained and leveled. Later flood control measures and raising of the ground level have dried the Campus Martius.

Approach Tiber Island from either side of the river. It's possible to drive over from the Trastevere side on the Ponte Cestio road bridge, a rebuilt version of the 46 BC bridge built by Lucius Cestius, but it's doubtful you would find a space among the thirty or so parking positions on the island. Much more pleasant is the walk across from the Piazza Monte Savello, near the Ghetto and the Theater of Marcellus, via the pedestrians-only Ponte Fabricio, the oldest Roman bridge that survives in the city. It was built for Lucius Fabricius in 62 BC and is still pretty much the way he built it. This bridge has long also been called the Ponte dei Quattro Capi by locals because of the two four-faced Janus herms that are mounted on the parapet of the bridge. (Janus is usually two-faced and looks up and down the road. Four-faced Janus images guarded only the most important intersections -- in this case of the River and the strategic road over the bridge.) If you walk to the island across Ponte Fabricio you will see on your right the 17th century rebuilding of the church of San Giovani Calibata and on your left the still impressive 11th century Pierleoni (later Caetani) tower and the fortress. The Pierleoni, a converted Jewish family, eventually produced Pietro Pierleoni who was elected Pope Anacletus II in 1130. Mostly because of his Jewish heritage, France and Germany rejected Anacletus and supported the Papal claim of Innocent II,. Anacletus and Innocent eventually died and the papacy was reunified by a new election in 1138. Anacletus is counted as an "anti-pope" although the church now records the fact that he was elected by the majority of the Cardinals.

The island is really quite small, about 67 meters wide at its widest point and 269 meters in length, but it has a very long history. According to an ancient Roman legend, the island formed over the wreck of a ship that sunk before the founding of the Roman republic in the 8th century BC. Although actual evidence is lacking, it's possible that the legend is true, since the island really is a silt bank that formed in the bend of the river, just as one would form downstream of an obstacle. Even today, when the river rises Tiber Island accumulates a burden of flotsam (natural stuff that floats into the stream) and jetsam (manmade stuff that gets thrown into the stream). All of it is removed annually to avoid periodic disastrous blockages of the River. How disastrous it might be is demonstrated by what happened after Nero's "cleanup" of Rome after the fire -- he dumped the debris into the river above Tiber Island. That caused a serious flood of the Campus Martius and, when the debris finally broke loose, the surge caused a very expensive change in the river's course down at Ostia. Presumably flood-control measures taken since Nero's time and especially in the last hundred or so years could lessen the impact, but why take chances.

Archeologists say that the oldest human settlement in the Rome area was on the island -- it originally was the safest spot around. Eventually, as weapons' throw-weight and range improved, it became necessary to control the overbearing Capitoline Hill, and, if you were going to do that, you might as well move up there and fortify your positions in earnest. That happened in the 9th-8th centuries BC by latest estimates. The island retained strategic and commercial value, however, and was always used for something. Early on, Romans determined empirically that isolation of diseased persons limited contagion, and the island became, first, a place to abandon the sick and, eventually a place to treat them.

The Aesculepius legend later associated with the island is the way Romans explained the quarantine function. The story goes that a plague was raging through Rome in the middle 290's BC, and, after consulting the Sibylline oracular books, the Republican government sent a delegation to the Aesculepion in Epidaurus, Greece, to retrieve an image of the healing god. The ship returned to Rome in 291 not only with the desired image but also with a huge snake (a major symbol of Aesclepius) that had come aboard and nestled in the cabin of the head of the delegation. The question of where to house the newly arrived idol, which had been avidly discussed both on board and ashore, was peremptorily decided by the serpent, which slipped over the side and swam to the island. A new temple to Aesculepius was built on the spot where the snake made its new abode next to a spring, and the spring, being thus sanctified by Aesculepius, was said to have healing powers.

The remains of that Tiber Island Aesculepion are thought to be under the church on the downstream end of the Island. The Holy Roman Emperor Otto III dedicated the first church on the site to St. Adalbert at the end of the tenth century, but Otto is also said to have enshrined the relics of St. Bartholomew the Apostle in the church. Adalbert was soon forgotten and the church acquired the name of St. Bartholomew, perhaps because Bartholomew, according to popular mythology, had been skinned alive: his resulting supposed protection of people with skin diseases tied in neatly with the island's medical tradition. Inside the church is a carved wellhead, which, some say, marks the spot of the spring of Aesculepius and the snake. Nineteenth century excavations under the church, in the course of one of its many rebuildings, found many artifacts associated with the cult of Aesclepius.

Once the church complex took over the cult site, a new medical center was needed, and it gradually grew until now the entire upstream end of the island is covered by the modern hospital. It was in an earlier version of this hospital that, according to legend, Rahere, a roisterous member of the court of King Henry II of England, recovered from malaria and had his vision of St. Bartholomew. That reformed him, made him a monk, and caused him to found the great hospital of Saint Bartholomew in London in 1123. Since 1548, St. Bartholomew's hospital on Tiber Island has been administered by the Fatebenefrateli religious order of monks -- their name means "do-good Brothers".

The Tiber Island is now completely surrounded by a modern stone-over-concrete platform, which you reach by a stairway on the Trastevere side of the island, near the hospital entrance -- it's across the piazza from the church of St. Bartholomew. The platform, especially on the Trastevere side of the Island, accumulates a lot of debris between annual pre-winter cleanups, but it is usually cleared by the end of November.

A walk around the island on the platform is quite pleasant. A slow circumambulation takes less than three-quarters of an hour, unless you dawdle, as we did, at the small dams to hear the rushing water and to see the impressive undertow. (Under no circumstances should you enter the water anywhere near those dams when the water is running high . We watched as the undertow repeatedly pounded a telephone-pole-size log down to the bottom -- we could hear it strike and feel the ground shake. The police station on the island maintains small rescue boats, but, because of the undertow, they are more likely to recover remains than effect a rescue.)

There are two other things to see while walking around the platform.

Under a stairway leading up to the police station on the island's downstream end is the remnant of the ancient Roman travertine decoration of the Island as a warship. You can see the ship's prow with its protruding ram (rostrum) and Aesculepius' snake climbing aboard. From the same end of the Island you can also get the best available view of the Ponte Roto (Rotten Bridge), which is the only remaining arch of the ancient Ponte Aemilius build in 179 BC by Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who also built the Basilical Aemilia in the forum.

Internet links:

The "unofficial" Tiber Island Internet site: http://www.isolatiberina.it/

Old prints and new pix of the Island -- the oldest (1491) clearly shows the flour mills that once took advantage of the fast current around the island, and

http://www.siba.fi/~kkoskim/rooma/pages/TISOLATI.HTM

Tiber Island Maps, old (1551) to recent (1993):

http://digilander.iol.it/isolatiberina/B_Mappe_e.html

Very good pictures: http://myweb.lmu.edu/fjust/Rome-Tiber.htm

Pictures and text: http://www.geocities.com/Paris/Arc/5319/roma-c8.htm

-------------------------

What's on the Tiber Island?

The bridges spanning the divided river date from ancient Roman times.

Pons Cestius. (30 BC). The other superb bridge links the island to Trastevere on the west. On the pillars there used to be statues of Gratian and Valens who rebuilt the bridge in 369 AD.

The Isola Tiberina, the Tiber River's only remaining island (till the Middle Ages there was at least one other) is boat-shaped and was clad in travertine in ancient times to disguise it as a ship. Its marble stern downstream is still visible today. The picturesque central square is dominated by a hospital that enjoys a good medical reputation and a superb view of the riverbanks.

San Giovanni Calibita. Annexed to the hospital is this lovely late Baroque church with the best painting on the island, Mattia Preti's "Flagellation of Christ".

Caetani Tower. This tower was built before the year 1000 by the Pierleone family who were of Jewish origin but produced Anacletus II, a powerful 12C anti-pope. It was the strong point of the adjacent Pierleone-Gaetani Castle.

Pierleoni-Caetani Castle. Another Medieval tower construction which served in 1087 as a refuge for the great champion of the Popes against the German emperors, the Countess Matilda of Tuscany and for several fugitive popes who fled from their enemies to be protected here by the impregnable Pierleone family, later followed by the equally powerful Caetani.

History:

293 BC. The island entered medical history during a plague when the Roman Senate sent envoys to consult the medical god Aesculapius in Greece. They returned with a miracle-dispensing snake, which slipped overboard at this spot in the river. The temple was built where the snake landed, serving as a hospital for many centuries.

12C. Rahere, court jester to King Henry II of England, recovered from malaria in this hospital which was then attached to the Church of St. Bartolomeo allíIsola. He returned to London where he founded what is still known as St. Bart's Hospital.

19C. Until the river was tamed at the end of the last century by isolating it from the city with high banks, there were flourmills on pontoons floating on either side of the island. Old lithographs show these small buildings which used the river's current to grind up wheat for Rome's daily bread. This flux often waxed too strong and the flimsy edifices were washed away.

Painting of Tiber Island by Ettore Roesler Franz

from his "Disappearing Rome" series. The wooden structure on pontoons in

the river is one of the famous flour mills that were moored to the Island

until the river banks were

raised in the late 19th century.

St. Bartolomeo allíIsola: The Baroque facade masks a church built in the 10 C by the Holy Roman Emperor "the wonder of the world", Otto III. Fancying himself as a fitting successor to the Caesars, Otto III personally installed two Popes, Gregory V, the first German pontiff, and Silvester II, the first French one. He built this church, which he could see from his palace on the Aventine Hill, on the ruins of the 3C BC Temple of Aesculapius.

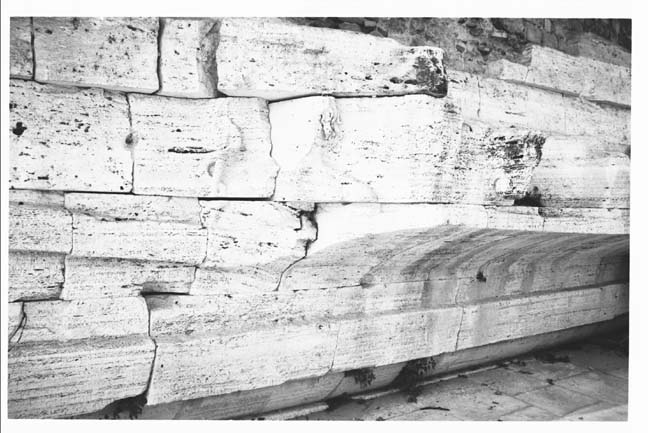

The altar step (beautifully carved

in the 12C) shows that there used to be an ancient spring of sacred medicinal

water here.

THE MILLS ON THE RIVER TIBER

written by Sergio Caggìa with Paul Gwynne for © Nerone the Insider's Guide to Rome

Below: photo of one of the last Tiber River Mills

INTRODUCTION

Since ancient times bread (and flour)

has been the staple diet for mankind; its production at the foundation

of civilization itself. Milling and grinding wheat is one of the cleverest

adaptations of the wheel, while water has been a source of energy for millennia.

Wherever possible large mills, built to serve growing communities, were

powered by water. It has been calculated that in ancient times the larger

mills could grind 7 kgs of grain per hour if slave powered but as much

as 150 kgs per hour if water powered.

HISTORY

At the archaeological sites of both

Pompeii and Ostia Antica there are examples of animal powered mills. The

first water mills in ancient Rome were on the slopes of the Janiculum hill,

powered by the waters falling from an aqueduct built by the emperor Trajan.

These mills produced flour up until 537 AD when the invading general of

the Goths Totila smashed the aqueducts to deprive the besieged city of

water. According to the contemporary historian Procopius the ever resourceful

Romans moved millstones and paddles onto boats down the river, establishing

the first floating mills on the Tiber. These floating mills were lined

up between the ancient bridge of Agrippa (today the Ponte Sisto) and Tiber

Island, i.e., where the river was protected by the city walls. From then

up until the beginning of the nineteenth century water mills were to be

found crowded on the river.

OTHER LOCATIONS

In the Middle Ages other mills were

built on a small tributary of the Tiber, the Marrana (its name is derived

from Acqua Mariana, the Marian Water). This river which at the end of last

century was channeled into underground canals, flows from the Alban hills

along the Via Tuscolana and Appia Nuova to Porta San Giovanni; it then

follows the city walls enters the city at Porta Metronia, passes the baths

of Caracalla, crosses the Circus Maximus, flows by the church of Santa

Maria in Cosmedin to finally end in the Tiber. When Pope Paul V (1605-21)

restored Trajan's aqueduct mills were once again built on the Janiculum

and powered by the restored waters of the Acqua Paola.

THE MILLS

While the mills on the Janiculum

and on the small Marrana were stone-built, the floating mills on the Tiber

were made of wood. They were simply constructed by placing two houseboats

together with a wheel in between . The main houseboat (always on the bank

side) would house the millstones, the gears and the grain to be ground.

The mill would be moored on the river bank to a tower or, in some cases,

an ancient column. A stone footbridge and gangway would connect the mill

to the neighbouring bank. Donkeys would be used to transport the grain

across the bridges and take the flour to the bakeries. The smaller mills

would be run by a staff of as little as four: this would consist of two

caricatori (those who load and unload the heavy bags of grain and flour);

one servitore (who would actually work on the boat) and one aiutante (assistant).

In the larger mills like those on the Janiculum there would also be a director

and a more labourers employed.

DANGERS

The mills floating on the Tiber were at the mercy of the unpredictable river currents. A heavy rainfall in Umbria or northen Lazio would swell the river and rise the water level in Rome, while periods of continuous rain would cause disastrous floods. Often the moorings were insufficient to resist the violence of the waters and the mills would be carried off by the swift tides often with people still inside. Examples of mills crashing against bridges (causing further damage to both bridge and mill); or wedging in the arch of a bridge damming the river and thus causing the waters to rise higher have also been recorded. Moreover, the artificial barriers used to direct the water onto the wheels would make the situation worse in the case of flood by impeding the flow. Floating mills were also a hazard for rowing boats and bathers. Indeed the tradition of children diving after watermelons thrown into the Tiber on Saint Bartholomew's day was later banned because of the number of accidents.

Despite the dangers, the floating

mills continued to crowd the river with the Millers' Guild (the Romana

Molendinariorum) becoming one of the most important and influential within

the city.

DECLINE

At the beginning of the nineteenth century there were about 20 mills active on the river, serving a population of c.158,000. Those under the "custody" of Tiber Island were the mills of SS. Annunziata, S. Bartolomeo, S. Francesco, Giuditta and S. Maria (the last lost in the flood of February 1855). By the end of the century, however, these had for various reasons all but disappeared.

With the establishment of the Roman Republic in 1798 the economic life of the mills was thrown into crisis. Wages fluctuated; the price of grain rose fuelling discontent between millers and bakers. Mill owners could not find people interested in hiring the mills and rents dropped. A further blow for the floating mills came on 1 September 1847 when the Presidenza dell'Annona forbade the transportation of grain and flour by pack animal, imposing instead the use of carts. Whereas the mainland mills were of easy access, it was impossible to drive a cart across the gangways to the mills on the river. The task of managing a floating mill thus became even more precarious. In 1870 three mills on the Tiber were lost in the terrible floods and never rebuilt. The surviving mills were gradually abandoned and had disappeared altogether by the 1880s when the modern embankment was built.