http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0401FirstWarEnd.jpg

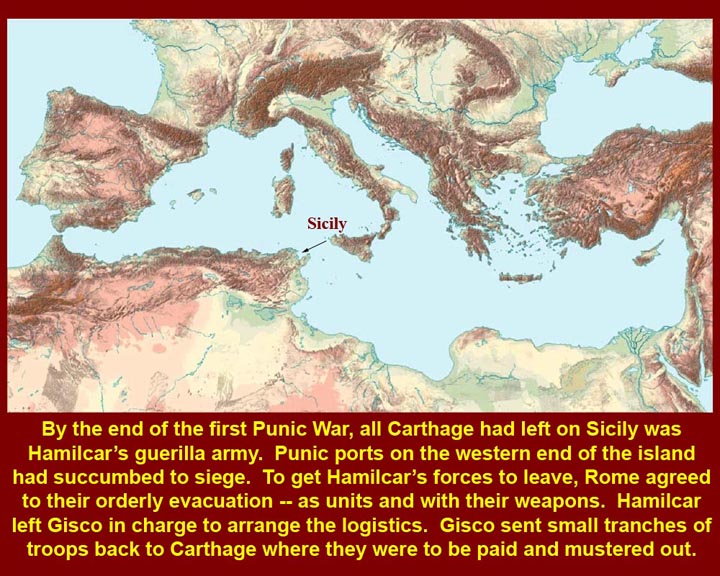

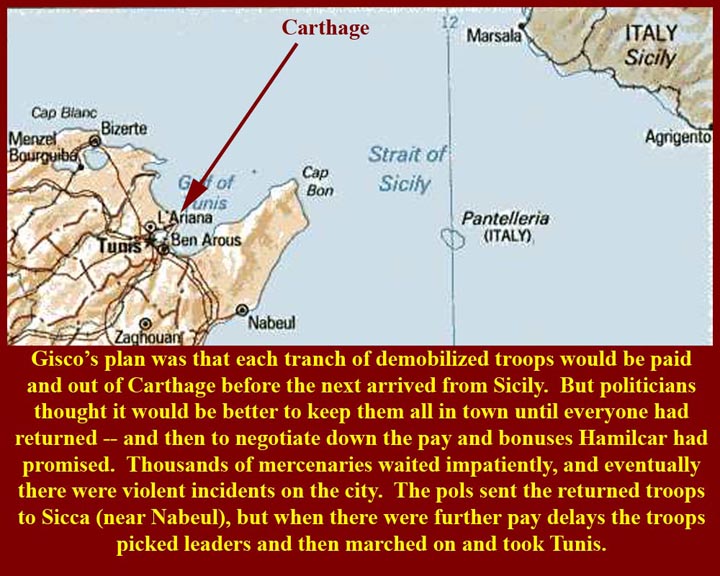

Hamilcar was conducting a Guerilla campaign against the Romans when the last two Punic cities in western Sicily surrendered at the end of the First Punic War. He was authorized by Carthage to negotiate a settlement. After rejecting a Roman demand that his force surrender its arms (which would have ensured their enslavement) he got the Romans to agree to an orderly evacuation (with their weapons) of all Punic forces from the Island. He also agreed to large war reparations that could be paid in annual installments. Hamilcar, who felt that he had been betrayed by shekel-pinching politicians in Carthage, then turned everything over to his subordinate, Gisco, and went home to his rural estate on the Cap Bon Peninsula. Gisco arranged to send the Punic forces back to Carthage in small groups to be paid off and mustered out. His plan would have prevented a concentration of mercenary forces in and around Carthage.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0402TunisCarthage.jpg

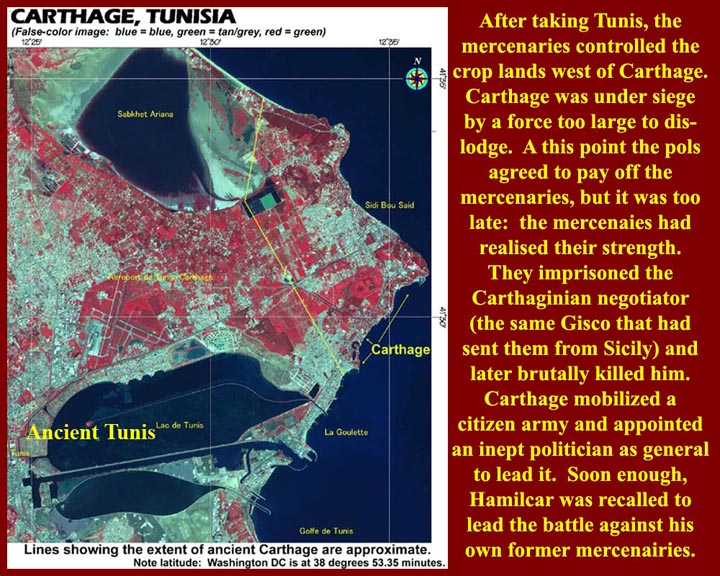

Carthaginian politicians, led by Hanno "the Great", had a better idea: they would keep the returning mercenaries in and around Carthage until they all had returned and then negotiate down the pay and bonuses that Hamilcar had promised during the war. Debate and delays fueled discontent, and ugly incidents started to occur in the capital. The politicians handed out a partial payment and sent the whole mercenary army off to a nearby town called Sicca. After further delays, the mercenaries chose leaders and marched on Tunis at the base of the peninsula on which Carthage stood. They took Tunis and cut off food shipments from the hinterland to Carthage. Faced with hunger and a huge mercenary army on their doorstep, the politicians finally offered full payment to the mercenaries. But it was too late: the mercenaries had now realized their strength.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0403CarthageBesieged.jpg

At the time of the mercenary revolt, the neck of the promontory was only about half as wide as it is shown in this satellite image. The food suply of carthage was outside the mercenary lines, so Carthage was in real trouble.

The mercenaries also besieged Utica, up the coast. Carthage sent Gisco to negotiate with the mercenaries, but they refused the Carthaginian offer and imprisoned Gisco with his negotiating team. Carthage appointed Hanno the great as its general and mobilized a citizen force to face the mercenaries.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0404aLibyanMercenaries1.jpg

About 40 percent of the returned mercenaries were Libyans, i.e., members of the indigenous North African population. They were easily able to enlist the support of the Libyan tribes which had long chafed under Carthaginian rule. The leader of the Libyan mercenaries was Mathos.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0404bLibyanMercenaries2.jpg

According to Polybius, Mathos and the other Mercenary leader, Spendius, feared that they would be executed if the mercenaries ever negotiated a settlement, so they instigated the torture and murder of Gisco and the other negotiators to ensure that the Carthaginians would refuse any offer to negotiate. They were right: from the time of the death of Gisco, Carthage sought only to exterminate the revolting mercenaries. All rules of warfare and negotiation were suspended. Polybius described the situation as a "truceless war", a term that is still used to describe a war in which no truce terms can be offered or accepted.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0405Utica.jpg

Hanno managed a victory against the mercenaries at Utica, but, according to Polybius, he didn't know scratch about protecting the city and soon found himself besieged inside. The rest of the Carthaginian politicians, with some trepidation, appealed to Hamilcar to take over the war against the mercenaries (he was to be "joint leader" with the immobilized Hanno.)

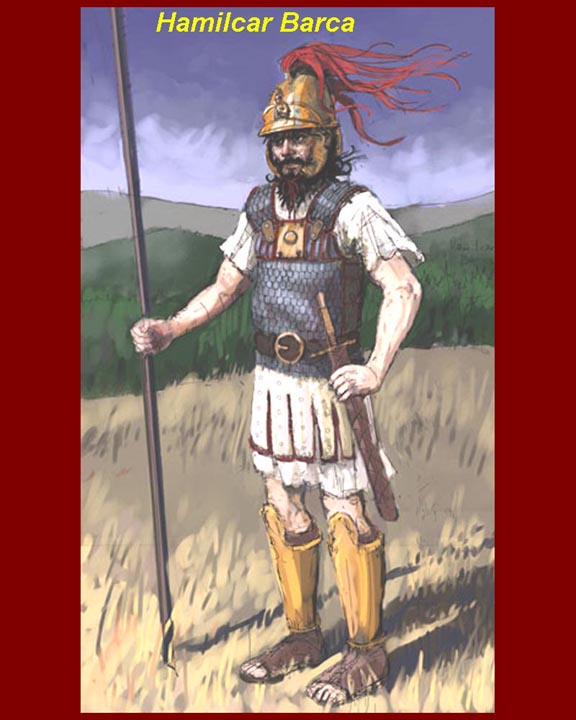

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0406Hamilcar.jpg

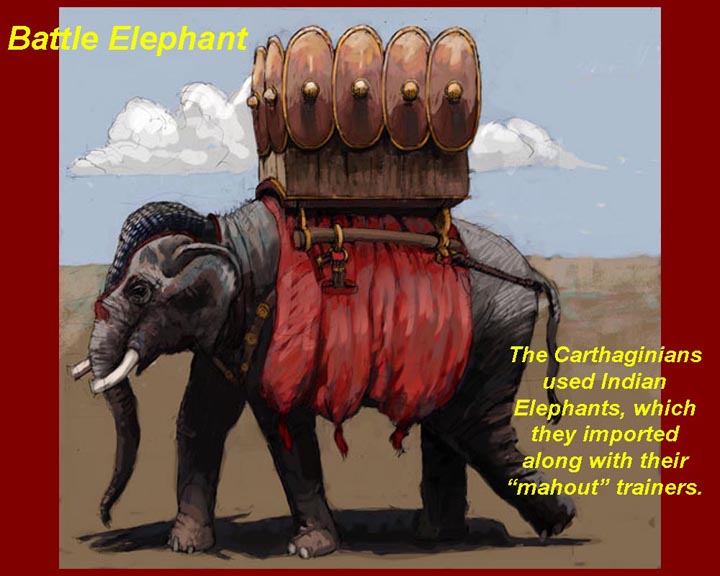

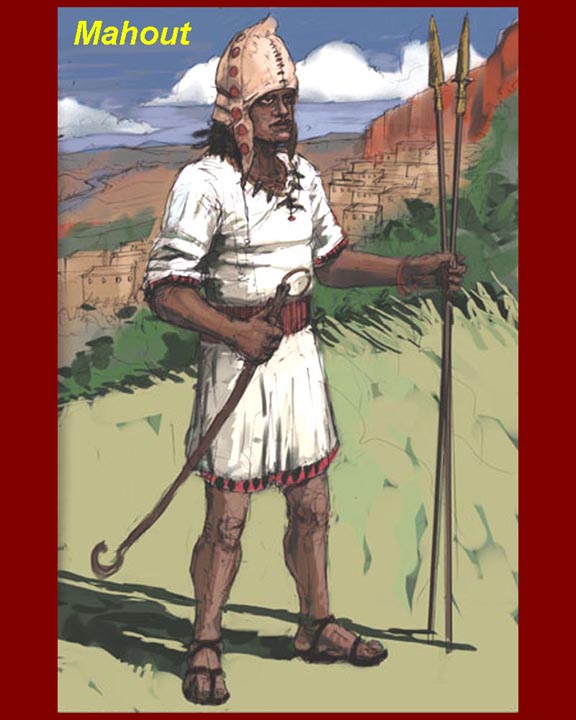

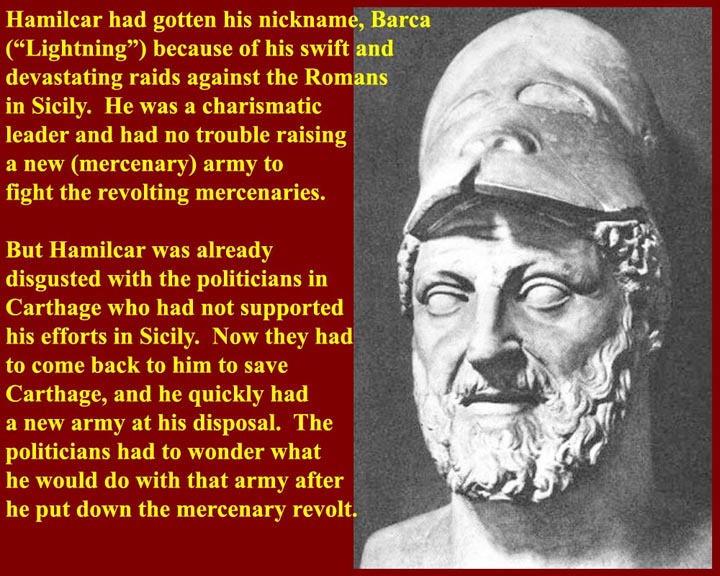

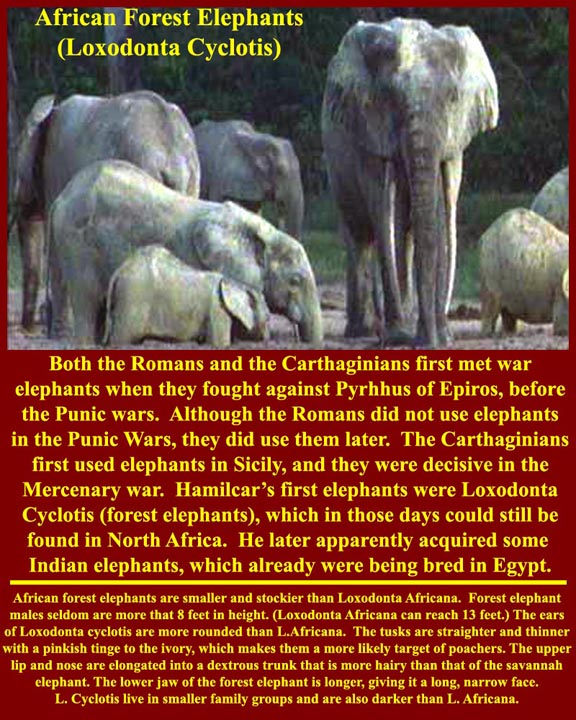

Hamilcar "Barca" ("Lightning", due to the swiftness and devastation of his guerilla raids in Sicily) was a charismatic leader and had no trouble recruiting a new mercenary army to fight his old mercenaries from the First Punic War. More importantly he squeezed the Carthaginian shekel pinchers for enough money to buy a new elephant corps.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0407HamilcarUtica.jpg

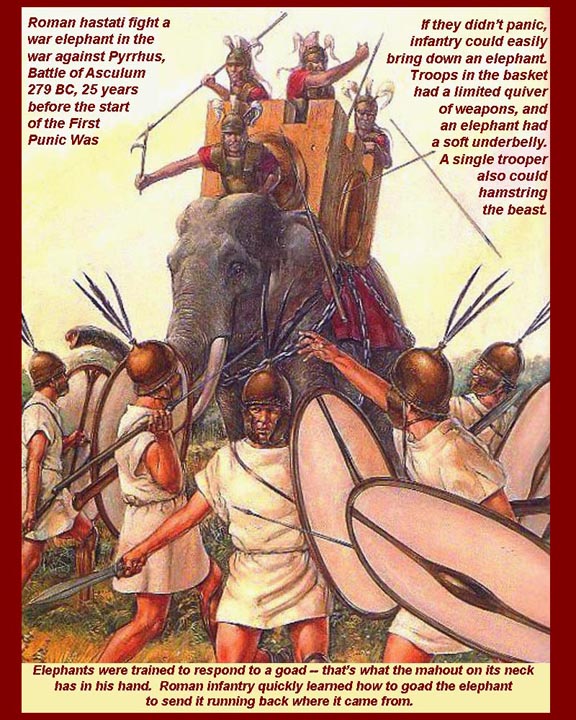

Hamilcar, when he was in Sicily, had been the first to put elephants in the Punic arsenal. They were to prove decisive in the three big battles of the Mercenary War: Utica, Bagradas River, and "the saw". At Utica Hamilcar surrounded the besieging mercenaries and then ran his elephants at them. Fear of the elephants (and no little fear of their former commander) broke the confidence of the Mercenaries. At the appropriate time, Hanno broke out with his elephants and the mercenaries fled. Hamilcar offered amnesty to captured mercenaries if they would join his force. Many did, and those who did not were exiled.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0408ForestElephant.jpg

Hamilcar's elephants.

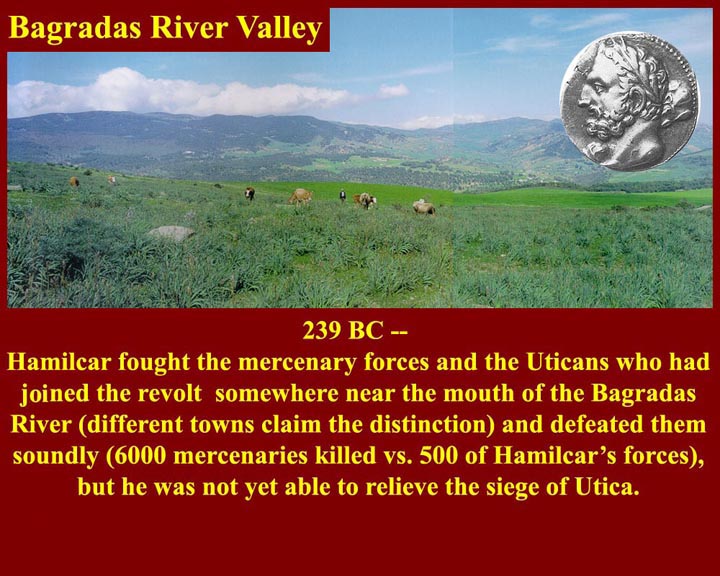

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0409aMedjerdaValley1.jpg

Hannibal also fought the mercenaries somewhere upstream from Utica, which, before extension of the river delta over the intervening centuries, stood at the mouth of the Bagradas River. The mercenary/Libyan force of 15000 was heavily defeated: 6000 killed and 2000 captured. Hamilcar's army lost 500 infantrymen killed. The main problems of the mercenaries were disorganization, factionalism, and lack of command experience in the mercenary leadership: Carthage (unlike the Romans) never allowed mercenaries into its officer corps.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0409bMedjerdaValley2.jpg

Tunisia's Medjerda River is the ancient Bagradas.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0410TheSaw.jpg

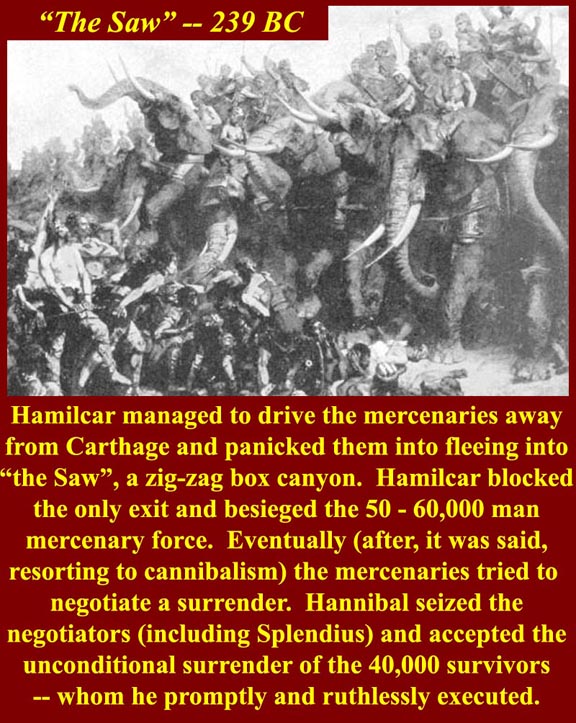

"The Saw" was a zig-zag box canyon where Hamilcar's forces trapped

the 50,000 or so remaining rebels. It was more of a siege than a battle (although usually sieges involve cities or fortresses. At any rate the rebels soon ran out of food, ate all their animals, and, according to Roman sources, finally resorted to cannibalism. They sent out negotiators, but Hamilcar imprisoned them. Finally, in desperation they tried to break out. After a short melee, the 40,000 survivors surrendered. Not needing any more new recruits, Hamilcar executed all 40,000.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0411Salammbo.jpg

Gustav Flaubert's 1862 French novel, Salammbo, is a romance about the love affair of a fictional Carthaginian princess, Salammbo (Hamilcar's daughter, no less), and the mercenary leader Mathos. Its sensual descriptions of Salammbo's love rituals and incantations made it an international sensation. But it's pretty tame by modern standards. The full English text of Flaubert's novel is available on the Internet at http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/gutbook/lookup?num=1290. The book inspired much art work, one complete and two incomplete operas, and a pretty strange sounding computer game (review link: http://www.justadventure.com/reviews/salammbo/Salammbo.shtm). Flaubert's story is not, of course, anywhere near reality, but generations of readers have learned all they "know" about Carthage from Salammbo. Flaubert got the name of his book from a suburb of Carthage, now a small town near Tunis city.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0412Sardinia.jpg

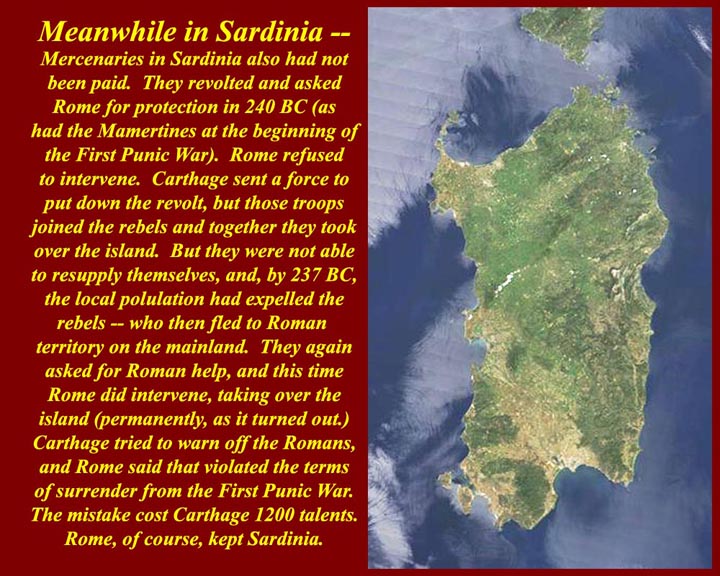

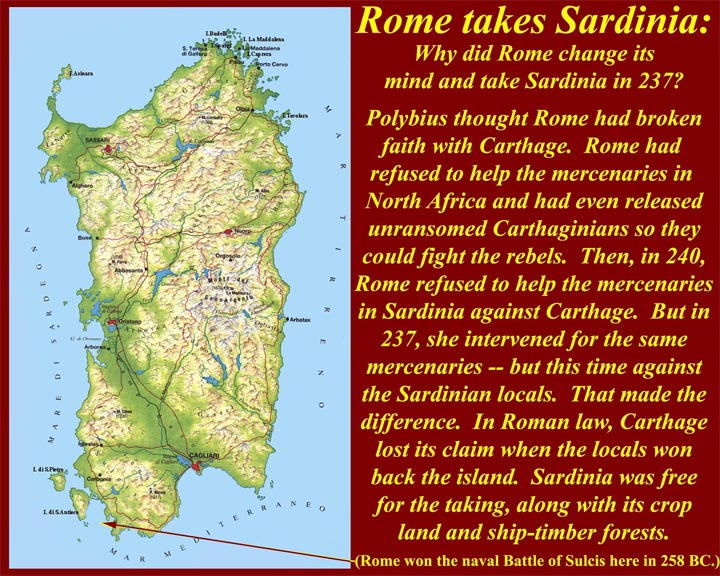

Mercenary troops in Sardinia (who also had not been paid) seized the Carthaginian territory in 240 BC and started selling off Carthaginian assets on the island: Sardinia was famous for its close-grained woods, useful for shipbuilding, and for its production of foodstuffs. The obvious customer was Rome. Many of the mercenaries on the island appear to have been from Roman territory, and they, like the Mamerrtines of Sicily at the beginning of the First Punic War, asked for Roman protection -- Rome refused. Carthage sent out a military expedition to put down the revolt, but the expeditionary troops, who were also mercenaries, quickly joined the rebellion. Eventually the rebels, cut off from military supplies from Carthage, were expelled from the island by the local Sardinian populace. They took refuge in Italy in 237 BC and again asked for Roman help. This time Rome responded with alacrity and seized the island. Italy still has it.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0413Sardegna-map.jpg

Carthage raged and threatened Rome -- a big mistake. Rome declared that the treaty ending the First Punic War had been violated and said war would resume. To avoid immediate resumption of war, Carthage had to cede Sardina to Rome and pay an additional 1200 talents in indemnity to Rome.

Polybius said that the Romans had acted in bad faith and simply had stolen the island while Carthage was engaged in the Mercenary War. But under Roman law, the Carthaginian claim to Sardina had lapsed as soon as the Sardinians had expelled the Mercenaries. Rome was, therefore, justified in seizing Sardinia. Nobody seemed to worry about the claims of the Sardinian natives.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0414HamilcarToIberia.jpg

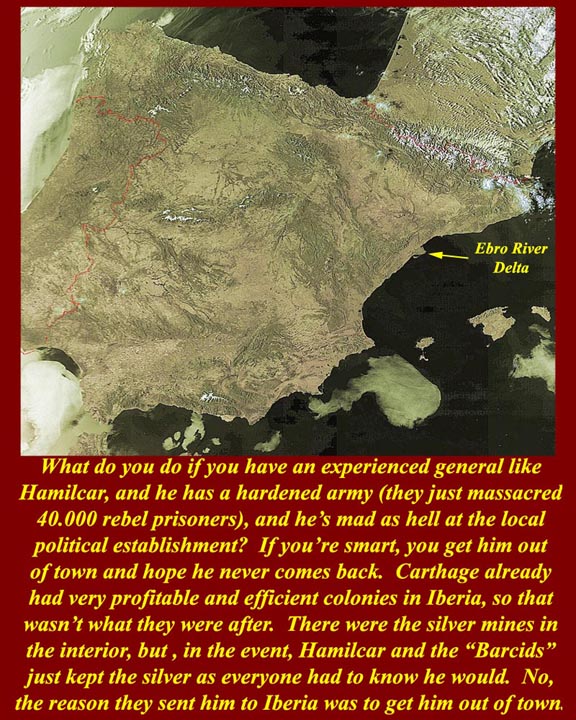

Various theorists have, naturally, come up with various theories about how Hamalcar and the "Barcids" (a modern nomination for his extended family and clientele) came to take over the Carthaginian colonies in Spain. Either they were handed Iberia to get them out of town, or they were sent to Iberia to exploit it for Carthage and they just kept the profits for themselves. It's clear, however what happened: the same year that he won the the Mercenary War, Hamilcar took off for Iberia with a large part of his loyal mercenary army. He quickly expanded into the interior and captured important silver mines: his coins and those of his successors are still marvels of silver purity.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0415HannibalOath.jpg

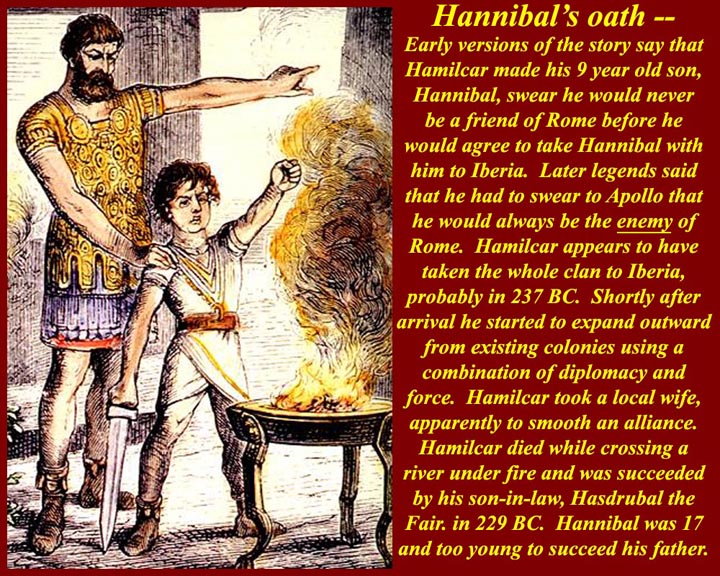

The image is a modern rendering of the oath Hamilcar is said to have administered to his nine year old son, Hannibal: in early versions of the story Hannibal swore to never be a friend of Rome; in later iterations that he would always be an enemy of Rome. Since no Carthaginian or "Barcid" version of the story survives, the whole episode is suspect. Polybius, however, did have Carthaginian informants, who could have witnessed (or made up) some such event. As usual, it is the problem of our single source (Polybius) for all later stories of Carthaginian events. There's no reason not to trust him, but, on the other hand, .....

Hamilcar drowned in 229 while crossing a river under fire while on campaign agains a Celt-Iberian tribe in the interior. He was succeeded by his son in law, Hasdrubal "the Fair".

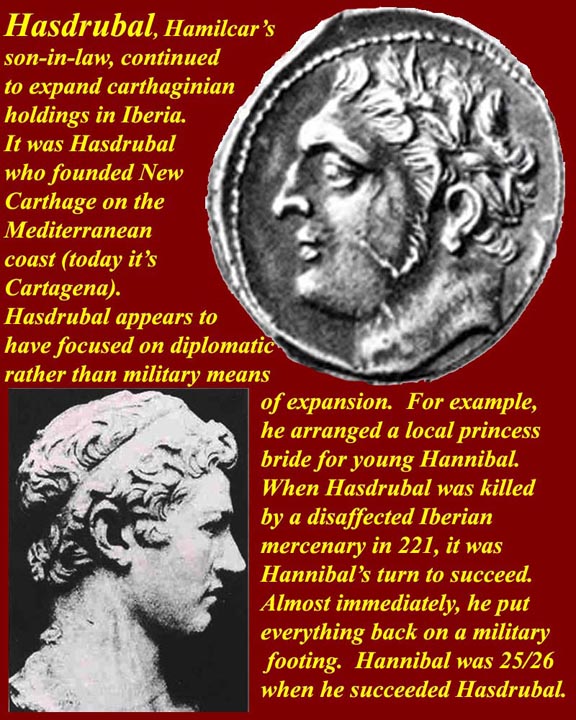

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0416HasdrubalSucceeds.jpg

Hasdrubal continued the Barcid expansion in Iberia, but he used diplomacy rather than Hamilcar's army. He married many of his subordinates, including young Hannibal, to Iberian "princesses" (daughters of tribal leaders). By 221 BC when Hannibal succeeded Hasdrubal (who had been murdered by a disaffected tribesman), all of the Iberian peninsula south of the Ebro River was under Barcid control. All, that is, except for the former Greek colony city of Saguntum which said it had informal protection of Rome. It was an obvious flashpoint.

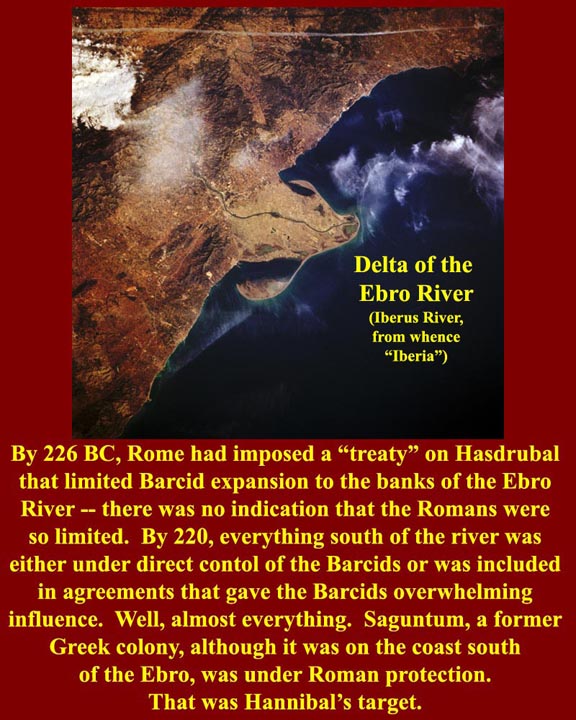

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0417EbroRiver.jpg

The Ebro Riber runs right across the Iberian Peninsula almost from the North Sea to its mouth at Tortosa. The Ebro, of course was the ancient Iberus/Iberos from which the peninsula and its inhabitants got their names. Already by 226 BC the Romans had imposed the Ebro as a limit of Barcid expansion. Hamilcar's expansion didn't take him that far anyway, and Hasdrubal's more pacific nature found the "border" agreeable. Hannibal was another story.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0418SiegeSaguntum.jpg

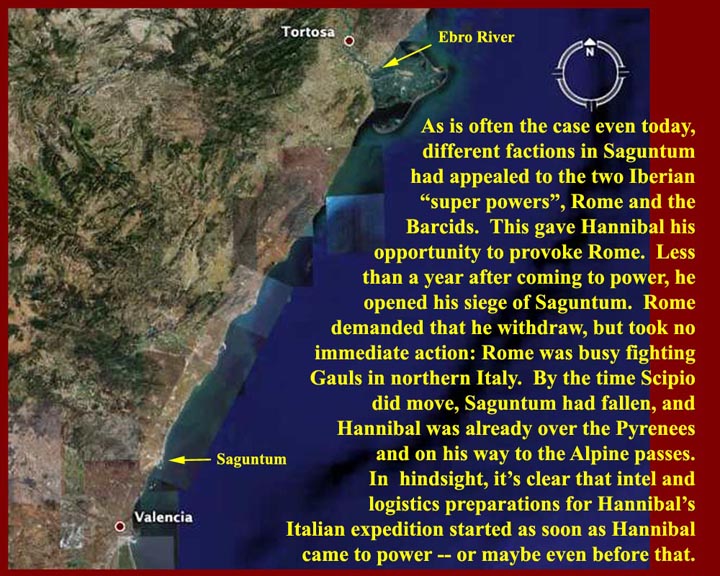

Within a year of coming to power in 221, Hannibal had Roman protected Saguntum under siege. It's not clear how the crisis started, but historians suggest that the "normal" pattern was followed: factions within the city appealed to the Romans and to the Barcids for assistance in gaining an edge over rivals. Hannibal jumped in with both feet, first putting the city under siege and then capturing it eight months later. Rome sent a warning. That had always worked before, but not this time. Hannibal undoubtedly knew that the Romans were embroiled in a struggle with Cis-Alpine Gauls for control of their territory below the southern slopes of the Alps. Because of seasonal transport problems, Rome couldn't respond, at any rate, until the next spring, and by then it was too late. Hannibal's successful defiance of the Romans played well with the tribes south of the Ebro and he was able, thereafter, to recruit a large army for the next stage of his plan.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAF0419SaguntumRuins.jpg

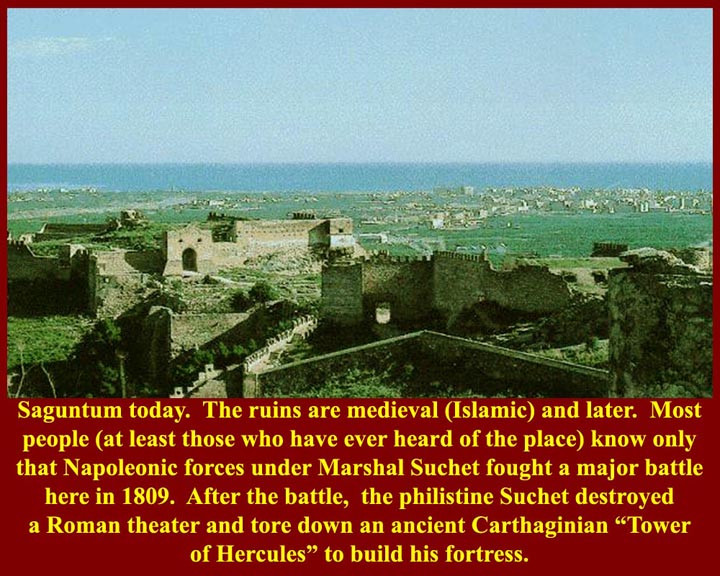

There are ruins to be seen today at Saguntum, but they are not from our period. Remains of a Cyclopic wall, millennia earlier than the Barcid siege can be found and much medieval and Napoleonic military stuff. The best Carthaginian and Roman remains were torn bown by Napoleon's Marshal Suchet to get materials for his fortress. (Pictures of a different Cyclopic wall can be found at http://www.cronenburg.net/wall.htm. The ancients, for whom these walls were already ancient, thought they were built by those one-eyed giants. We still don't know who built them, but they are all over Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Individuall stones are often meters thick and weigh more than three tons.)

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0420HannibalRoute.jpg

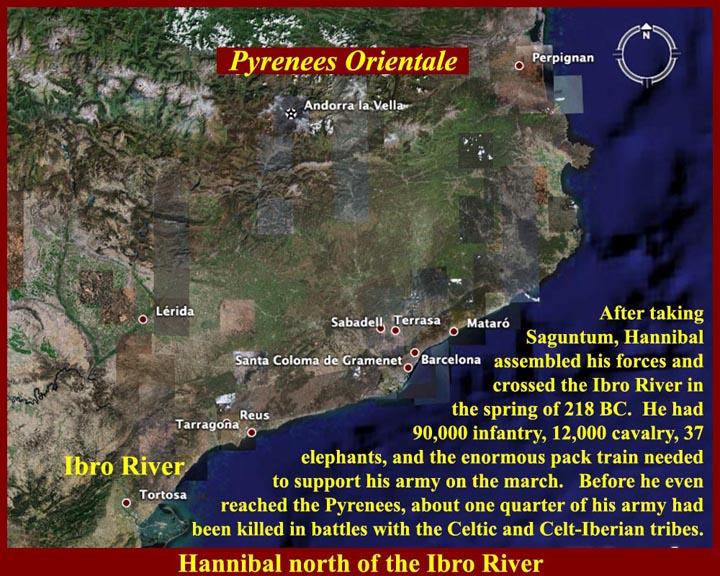

Hannibal's 8 month siege of Saguntum in 220 BC was just the beginning. He left a subordinate in charge of the city and went to New Carthage to assemble his expeditionary force. No army of its size had ever moved in this area of Europe: 90,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry, 37 elephants, and a huge pack train set off along the coast and across the Ebro River.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0421NorthOfIbro.jpg

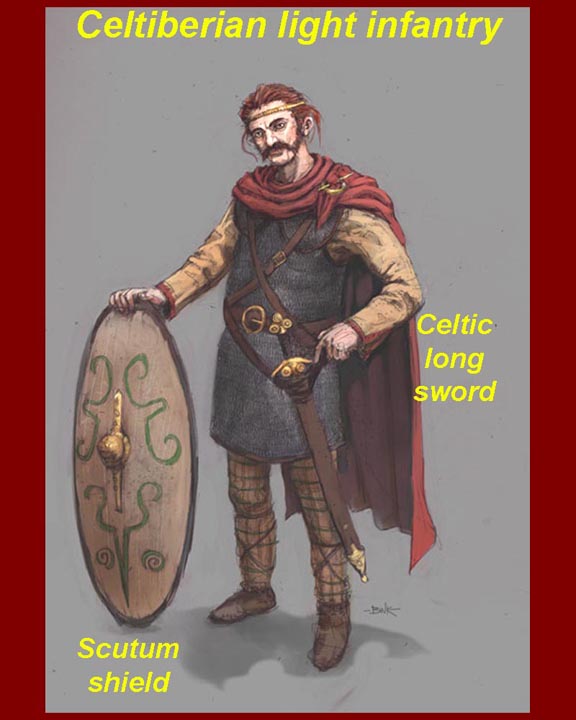

Hannibal's passage through Catalonia made no lasting impression -- no identifiable ruins, place names, local legends -- but the Iberians and Celt-Iberians certainly made an impression on Hannibal's army. More than a quarter of his force was killed in battle before he reached the base of the Eastern Pyrenees (Pyrenees Orientale).

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0422Catalonia.jpg

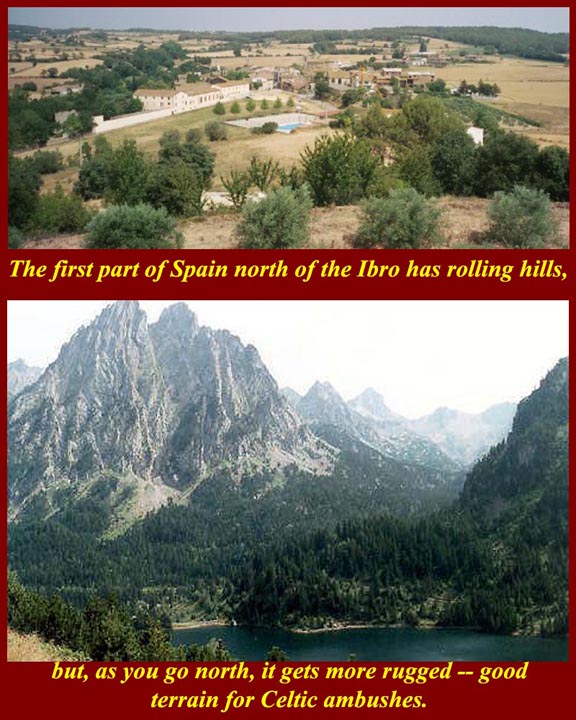

Southern Catalonia has gently rolling hills. The north becomes rugged and merges into the Pyrenees Orientale. Hannibal's forces were subject to ambush and guerilla attacks every step of the way.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0423PyreneesOrientaleMap.jpg

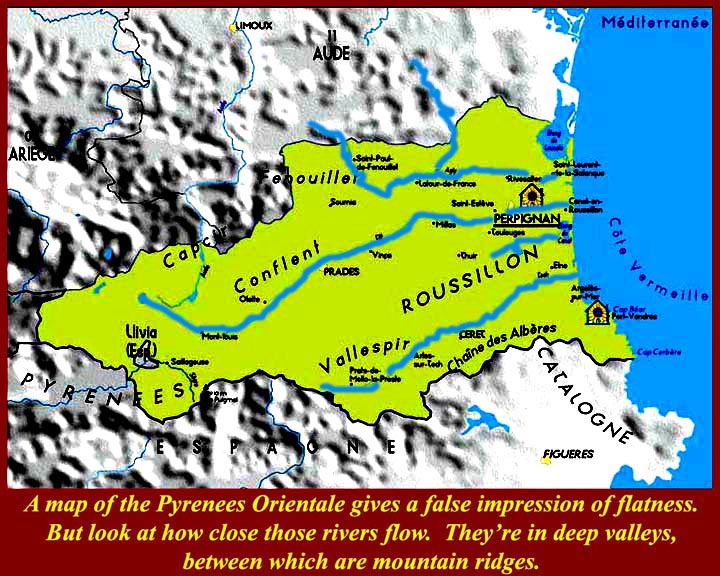

Maps by their nature are flat. But if they show numerous close together rivers flowing in the same direction, that means deep and narrow mountain valleys with high peaks between: no room for meanders here.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0424PyreneesPhotomontage.jpg

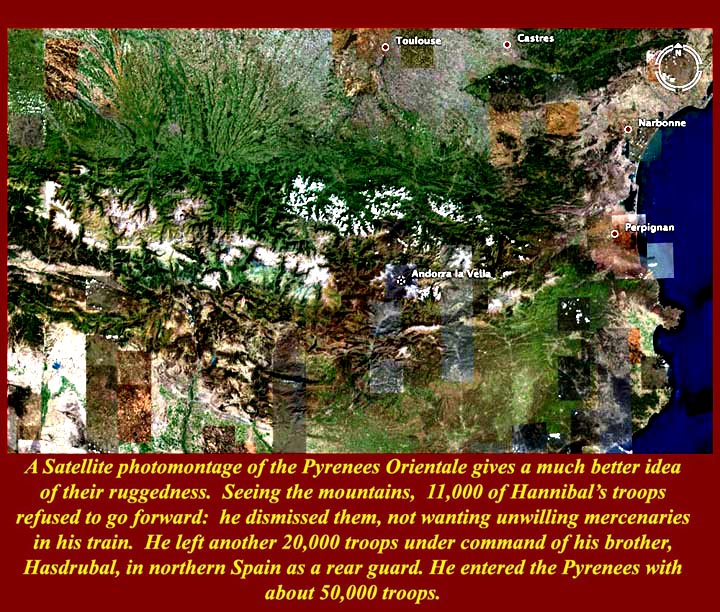

This Google satellite photomontage gives a better idea of the terrain. About 11,000 of Hannibal's mercenaries simply refused to make the climb -- they were probably flatlanders from southern Iberia. He discharged them and sent them home, not wanting to force discontented troop into the mountains. He also left another 20,000 under command of his brother, Hasdrubal Barca as a rear guard in the area that is now Catalonia. He had lost some 22,000 in battle, 11,000 refuseniks discharged, and 20,000 as a rear guard out of his original 102 thousand effectives. He was able to hire a number of Celt-Iberians as mercenaries, however, and probably entered the Pyrenees with more than 50,000 fighters (and the smaller but still huge pack train.) Ironically, after all the hard fighting on his northward approach to the Pyrenees the passage through those mountains was almost unopposed, and it was high summer by that time so it wasn't too cold.

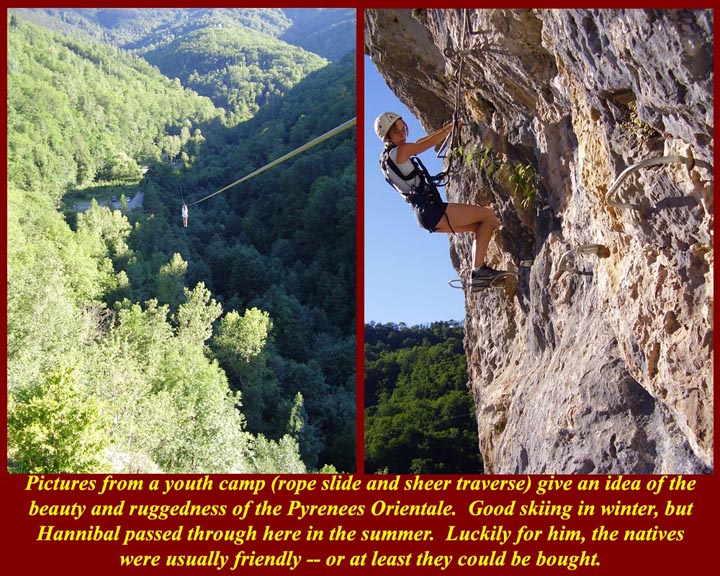

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0425PyreneesOrientaleCamp.jpg

Summer conditions in the Pyrenees can be quite balmy. Many Spaniards go to the mountains to escape summer heat and send their kids there for "adventure camp". The rope slide rider has a harness, like the one on the girl traversing the cliff. Note the already-established foot bars on the traverse: nobody wants things to get too adventurous. There's also a lot of good skiing in the winter.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0426Roussillon.jpg

On the northen side of the Pyrenees was what the Romans called Trans-Alpine Gaul, which was, of course, inhabited by Trans-Alpine Gauls. The Gauls were at first very suspicious, but Hannibal sent forth more agents (there had also been pre-arrival agents) to assure the leaders of the Gallic tribes that he was only seeking passage and not conquest. He invited the leaders to a grand congress where he lavishly distributed gifts. Their suspicions were largely overcome, so there was no real opposition to Hannibal, asside from some small random raids on his baggage train -- to good a target for the young punks to resist. Everything went fine until the Barcid expedition reached the Rhone River.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0427HannibalFrance.jpg

The march toward the Rhone was along an easy route. A Roman miltary road, the Via Domatia was built later on the same route, and so was the Euro-A9 "interstate" superhighway.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0428RhoneEncounter.jpg

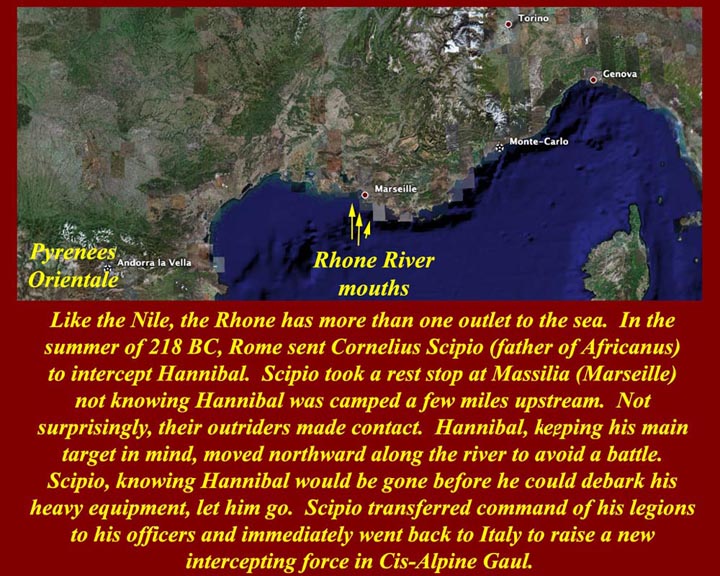

Massilia (modern Marseilles) was on one of the several mouthes of the Rhone River. Because it already had strong connections with Rome, Hannibal avoided the city and encamped his army several miles upstream.

About the same time Rome got word that Hannibal was on the move and sent one of its Consular armies under Cornelius Scipio (father of Africanus) to intercept Hannibal south of the Pyrenees. None of the Romans had any idea that Hannibal was already over the Pyrenees and camped on the west bank of the Rhone. (The other Consiular army was deployed in Cis-Alpine Gaul protecting new Roman coloniae that had been imposed on the Cis-Alpine Gallic tribes).

By chance, Scipio decided to take a rest break in Massilia. Outriders of his

forces and of the Barcid army bumped against each other north of Massilia -- the first indication that either force had of the presence of the other. The Roman cavalry put the Barcid riders to flight, but Scipio had no way to chase down Hannibal: all his gear was still aboard ship in the port. By the time he could disembark, Hannibal, he knew, would be long gone.

Hannibal also didn't want to fight Scipio along the Rhone -- his target was Italy and Rome, and, to get there, he had to reach the Alpine passes before the were blocked by snow. Hannibal led his army northward along the Rhone until he could find a way across.

Meanwhile, Scipio made a very wise and very un-Roman decision to turn his command over to subordinates (relatives -- other Scipios) and immediately took ship back to northern Italy where he raised another intercepting army. Hannibal's element of surprise had been lost.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0429RhoneWatershed.jpg

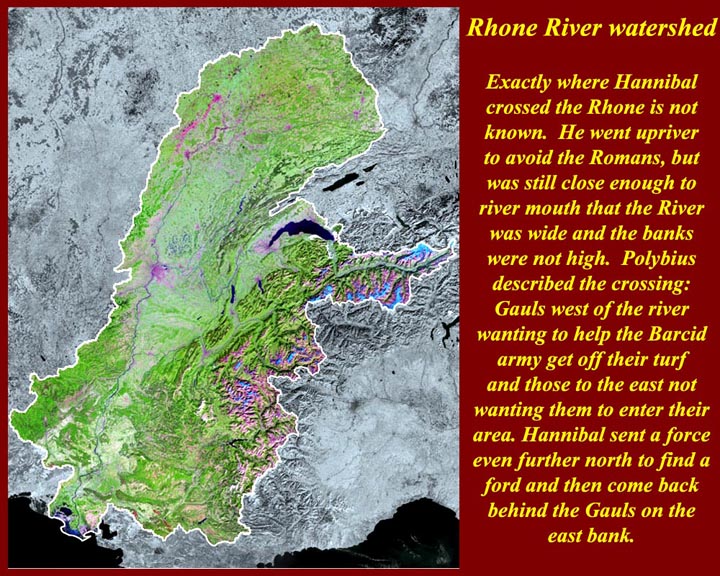

The Rhone flows southward along the western froon of the foothills of the French Alps and debouches into the Tyrhennian Sea (literally: debouch is from the French, meaning issues from the mouth). Hannibal's crossing point, like many things about his route from this point on is widely debated. It could not have been to far upstream, however, because the river at the crossing point was described as wide and with low banks. Clearly if would have been above the point where the river divides to flow through its several delta channels.

Wherever it was, Hannibal had a problem. The Gauls on the west side of the river wanted him to leave and were doing anything that they could to help him on his way. They gave him all their boats and taught his forces how to make dugout canoes and large rafts to take his men and baggage across. But the Gallic tribes on the eastern bank had assembled to prevent his crossing. Hannibal used the now standard solution. (It's standard because Hannibal's solution is now studied in "war colleges" all over the world.) He sent a cavalry detatchment -- about 300 horse -- upriver where they found a hidden crossing point. and came back down behind the tribes assemble on the east bank.

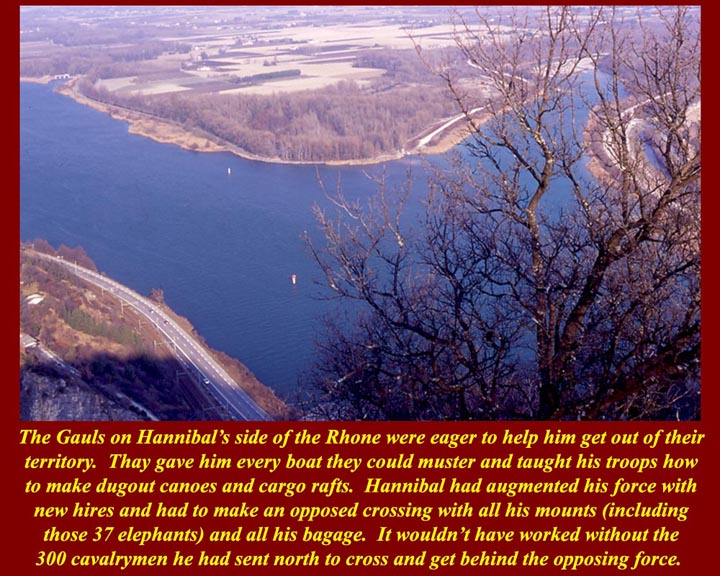

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0430RhoneCrossing.jpg

One of several proposed Rhone crossing points for Hannibal's army.

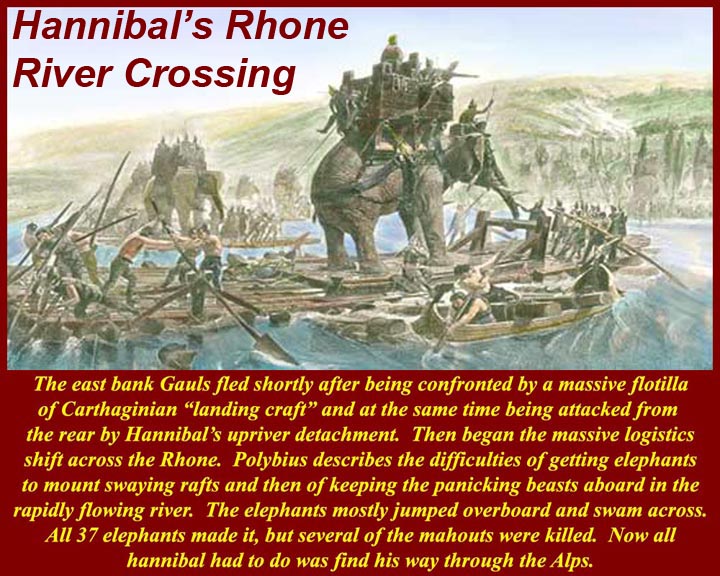

On the signal of his hidden cavalry detachment, Hannibal started moving his infantry "landing craft" across the Rhone. The Gauls started throwing projectiles as soon as the Barcid boats got in range, but then the cavalry attacked from the Gallic rear. Not knowing what was happening or the size of the attacking cavalry force, the Gauls retired in confusion, and Hannibal had control of both banks. He then brought across the remainder of his cavalry, the elephants (which didn't like the swaying rafts and jumped overboard, swimming ashore and killing several of their mahouts), and that still huge baggage train.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0431RhoneElephants.jpg

An artists conception of the elephants on rafts, drawn from the description given by Polybius.

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0432HannibalSeesAlps.jpg

Hannibal went further north along the east bank of the Rhone looking for a way into and through the Alps. Untrustworthy -- in fact traitorous -- Gaulish guides were available.

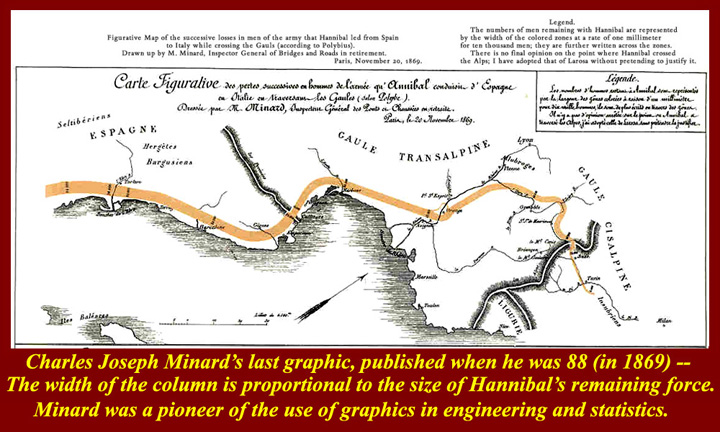

http://www.mmdtkw.org/CNAf0433MinardMap.jpg

Charles Joseph Minard was a French illistrator famed for his use of graphics to illustrate industria processe and, in retirement, for his graphic illustration of historic events. Minard did this illustration of the size of Hannibals invasion force the year before he died (at 88) in 1869.

Minard is most remembered for his 1861illustration of the losses of Napoleon's armies in their advance into Russia and in their retreat. (Various illustrations on the Internet at http://images.google.com/images?q=minard+napoleon)