ALRItkwRom303_6FranksHRE.html

Franks and Holy Romans

The Franks, for centuries, occupied a special position in Roman history -- not "barbarians" like all those other outsiders, but protectors -- saviors from the Byzantines and their machinations. But, as often happens, "protection" was sometimes a great burden on those being protected. The Papacy had been aggregating power for centuries and didn't want to share it, neither with the Byzantines nor with the Franks.

The Franks evolved into the "Holy Romans", and the relationship between Rome (the Popes) and Holy Rome (the Emperors) became rocky indeed. That wasn't really sorted out until the 19th century.

But it starts with the Franks.

Introduction:

Merovingians Franks are first noted in the deltas of the Scheldt and Rhine Rivers, along the North Sea coast from modern Antwerp, Belgium, northwest into The Netherlands. In 350 they became Roman Foederati and were allowed to move into better land inland along the Rhine.

They were Germanic -- just small tribal groups -- and had no overarching organization, but there were two general divisions (recognized first by outsiders and later by themselves), an inland group and those who lived closer to the sea, the later being the Salic or Salian Franks (assumed to be named because they were "salty" or seaward). The Salic Franks eventually dominate -- hence "Salic Law" as the basis of French law.

By 430 they had occupied central "France" (not yet called France) and had control over the imperial arms factory at Soissones -- so now the Franks have strategic value. They were a major component of the Roman led army of Aetius that defeated the Huns as Chalons in 451.

After Aetius was murdered by political enemies at Ravenna, they broke away, and when Odovacar dissolved the Western Empire and became king of Italy, the Franks were essentially free to do what they pleased.

In 481, 15 year old Chlodoweg (name from which came Ludvig, Louis, Clovis) became leader of his small Salian tribe. Leaders of all the tribes claimed to be descended from Wotan and thus they were all ostensibly "related" by (Wotan's) blood. Chlodoweg hit on the idea of killing off other members of this blood related "family", and within five years he had united the Franks under his personal rule. He clearly had a pretty powerful, or at least the most ruthless,"small tribe".

In 486, Clovis defeated the Roman general who had held the area around Paris (and who was waiting, like an unrequited lover, for the Empire to return) and Paris became the capital of the Franks.

Ten years later Chlodoweg defeated the Burgundians after taking an oath that he'd become a "catholic" Christian (i.e., not Arian) if he won the decisive battle (496). His baptism is the subject of many contemporary or later paintings.

In 507, at the request of the Eastern Emperor (and undoubtedly after a big bribe) Clovis started to chase the Visigoths out of Gaul, driving them out of their capital at Toulouse and into Spain. He gained southern France for the Franks by 508, but Theodoric, the Gothic Italian king, kept him from taking the Mediterranean coastal area. (Theodoric, a Goth Arian, had figured out that the whole maneuver by the Franks and Byzantines was an anti-Arian pincer movement.)

In 510 Clovis drove the Allemanni out of the northern Rhine and annexed the territory.

Then he died the next year (511) and Gavelkind, the bane of French and sometimes of English imperialism, took over.

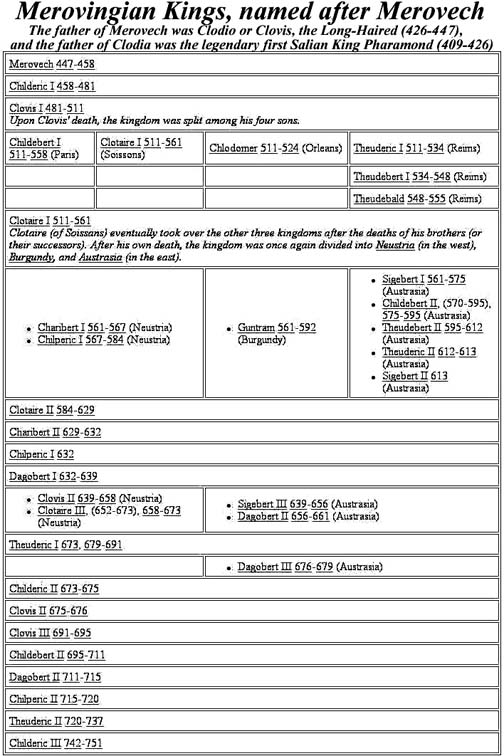

There were then four "Merovingian" Kingdoms (after Merovech, the semi-legendary granddad of Clovis), centred at Paris, Soissons, Orleans, and Reims, and they fought like cats and dogs. One of the four sons, Claotaire (equivalent to Lothair, Lothar, Luther, or Lothario) , eventually took over all four kingdoms as his brothers or their heirs died off, finishing the re-consolidation in 561, but then he died the same year and Gavelkind again divided the realm again into three parts, Neustria, Burgundy, and Austrasia, ruled by his three sons. We'll continue this stuff in the next topic, the Merovingians. Gavelkind is the equal distribution of wealth and property among male heirs, the opposite of primogeniture. [Gavelkind was still the law in England until 1926. -- tkw] Clovis had four sons and the Frankish "empire" which Clovis had so carefully unified, was split up at his death

[And another thing -- tying things together: Until the death of Clovis, Theodoric (who, you remember, was a Ostrogoth) was always on guard against Frankish expansion. When Alaric 2 died in 507 Theodoric inherited Spain, and he united Spain and Italy under his rule (thereby neutralizing, if not reversing that Frankish-Byzantine pincer strategy). As a further way of neutralizing Frankish and other Germanic threats, Theodoric used the "marriage weapon". He married his daughters off to Germanic kings -- he had no sons. The daughters were the result of his own marriage Audefleda, who was the beloved sister of that same Clovis of the Franks . The most important marriage alliance actually turned out to be that of his daughter Amalasuintha to Eutharic, a Visigoth Prince. Theooric had hoped to unite the Visigoths and Ostogoths, but Eutharic died when the resulting son was just a little boy and that little boy inherited the Italian throne from Theodoric. Amalasuintha ruled Italy as Regent and Principa (Princess) when Theodoric died in 526. She lasted until Belasarius came roaring in and took Italy back for Justinian and the Byzantines and meanwhile devastated the city of Rome in the process.]

More info:

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06238a.htm

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/gregory-hist.html Gregory of Tours -- 6th century history, full text

http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Frankish_Kings

http://www.american-pictures.com/genealogy/persons/per02030.htm Audefleda

A chart of all the Merovingians and Carolingians is at http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Frankish_KingsThere were 37 Merovingians in all if you count all the way back to the first Clovis/Clodio and his semi-mythical father, Pharamond.

The gavelkind problem sorted itself out and then reasserted itself several times.

But ultimately, it didn't matter. By the end of their line, the Merovingians had become the "Les Rois Faineants" -- "The Do-nothing Kings". In Italian terms, they believed in the "dolce fa niente" -- the "sweet do-nothing". Their interests were dogs, horses, falcons, and women -- some said in that order. Actual rule had passed into the hands of their chief bureaucrats, the Major Domi -- usually translated as "Mayors of the Palace" in English. At some times there were inter-regnums when the Mayors simply ruled.

In the Austrasian Merovingian Kigdom, there was a line of Mayors from the Metz region, and one of them, Pepin 2 of Heristal (680-714) annexed the Neustrian Kingdom to Austrasia, and thereafter there was again only one Frankish realm. Pepin 2 had legitimate sons who succeeded him as Mayors when he died in 714, but his illegitimate son Charles ousted them in 719.

Charles defeated the invading Saracens in 732. The Saracens fled overnight after being hammered by the Franks on the first day of the Battle of Poitiers -- and Charles picked up the sobriquet "Martel", "The Hammer".

Charles Martel had two sons who succeeded him as joint Mayors of the Palace (741), but one resigned to become a monk in 747, leaving Pepin 3, The Short, in sole charge. [Sobriquet \So`bri`quet"\ (s[-o]`br[-e]`k[asl]"), n.(French sobriquet, OF. soubzbriquet, soubriquet, a chuck under the chin, hence, an affront, a nickname; of uncertain origin; cf. Italian sottobecco a chuck under the chin.) An assumed name; a fanciful epithet or appellation; a nickname; e.g., Martel (from Marteau -- a hammer).] With the connivance and blessing of Pope Zachary , Pepin siezed the throne from the last Merovingian, Childeric 3, in 751. (and five years later {756}, Pepin reciprocated by giving Pope Stephen 3 the "Donation of Pepin", the "Roman" parts of the Italian lands Pepin had taken from the Lombards and from the Byzantine Exarchs.)

Pepin, The Short, was, of course, the Grandfather of Charlemagne. Although the next dynasty was named "Carolingian" after Charlemagne, the Austrasian Mayors from that Metz line are usually also counted as Carolingians. That's why it sometimes appears that the French Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties overlap by about 150 years.

More info:

http://genealogy.euweb.cz/merove/merove1.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merovingian_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merovingian_art

Carolingians

Meanwhile, back in Rome -- As noted, the "Carolingian" name was and is still applied retroactively to all those Metzian Mayors, but either Charlemagne, or, with a stretch, Pepin 3, was really the first. In 660, while Pipin of Herstal was still an apprentice Mayor in Austrasia, the Eastern Emperor, Constantine 2, visited Rome for a week with a sizeable army and entourage. Their main employ while in Rome was theft of bronze and lead from roofs of surviving ancient building and from the clamps that held the stonework together. They loaded three shiploads of metal at Ostia and sent the cargo vessels on their way to Constantinople. En route the ships were intercepted and captured by Saracen pirates. Some of the metal went to Jerusalem, and, according to records still there, the lead sheathing on the roof of the Dome of the Rock and the al Aqsa Mosque, came from Rome.

Without the metal clamps, buildings started to tumble with every earthquake, and unsheathed wooden roofs rotted and fell in. The devastation of Rome's monumental structures far outstripped whatever "Barbarian" marauders had accomplish in the preceding 300 years. Rome's large sewer lines, also clamped with lead, broke open and the largest, the Claoaca Maxima, built in the ancient Roman monarchical period broke flooding the forum. Aqueducts, meanwhile collapsed -- no clamps to hold them together -- reducing the city's water supply, and the remaining sewers blocked up because there wasn't enough flow-through to flush them out. Rome, and especially the low-lying forum area, became a stinking mess, polluted with human and animal wastes. The population was already drastically reduced (and, also, weakened Rome had gotten no new drafts of captured slaves) so there was not enough manpower to make the repairs that could save the situation. The move out of the center of the city and into the Campus Martius accelerated.

[the "good side" of the pollution of the Forum was that it actually saved many of the ancient buildings there. Some of them were simply buried in the accumulated stinking muck. Even the parts of buildings that rose above the level of the ordure were preserved. "Miners" would rather go almost anywhere than into the horrible mess in the Forum to look for marble and limestone either for re-use or to feed lime kilns. A lot was left when archeological excavation finally began in the late renaissance and again in the late 19th century.]

Romans were horrified by the devastation wrought by Constantine 2. In the next century Rome learned other reasons to hate the East.

For one thing, sea routes needed to bring food, commodities, and defensive forces to defend the weakened cities were lost to the Saracens -- the fate of the three ships of lead and bronze was only one example. Eventually the Saracens engaged in internal conflict -- their Umayyad dynasty collapsed in the midst of the first Sunni v. Shiat-Ali civil war. The upshot was a new capital in Baghdad and a new Abbasid dynasty. But civil war in the Islamic east just led to anarchy in the Islamic West -- North Africa -- and uncontrolled Saracen piracy around Italy.

The Eastern Empire, which the Romans and Italian had relied on for support against the Saracens, became preoccupied with the arrival of the Slavs on their northern and eastern borders. The Eastern Imperial Navy declined (just when the West needed it most) as Eastern land forces were augmented. Meanwhile the Easterners started to fight among themselves over icons.

There was also a period of Frankish consolidation and land expansion, during which the Franks also turned their attention away from the Mediterranean, but that didn't last.

Pepin appeared on the Italian/Roman horizon just when he was needed. The Lombards had been fighting intermittently to throw the Exarchs out of Ravenna, and finally succeeded, but in doing so they had also exhausted themselves. Frankish forces came rolling into the vacuum and Pepin, The Short, paid off his debt with the "Donation of Pepin" in 756. Italy, down to a line halfway between Rome and Naples, was nominally Carolingian, but it was to be ruled autonomously by the Popes. More importantly, vast tracts of land were transferred to Papal ownership providing much-needed income to the Papacy.

The Donation and the Frankish -- later French -- "protection" was to be a feature of Papal politics until September 19th, 1870, when the last French garrison was pulled out of Ostia to futilely reinforce French armies in the Franco-Prussian war. The next day the Bersagliari broke through Rome's northern wall, the city fell, the Papal States disappeared, and Italian "Re-unification" was completed. Pepin's grandson, Charlemagne, finished unifying the vast Frankish Empire -- from the Atlantic and the Pyrenees to the Oder River (through Poland) and From the Baltic Sea to Central Italy. Division of Charlemagne's Empire By the end of the 8th century, the Byzantine (Eastern) Empire was weakening, and Charlemagne had a plan to marry his Daughter, Rotrud, to the Issaurian Byzantine heir, Constantine 4, whose mother, Irene the Athenian, was ruling as Empress until he came of age. (Some sources say Charlemagne also planned to marry the widow Irene.)

The Sequel was that Charlemagne, and his former tutor, now Chief of Staff, Alcuin, went to "Plan B", and Constantine visited Rome where he was crowned as "Roman Emperor" by Pope Leo 3 on Christmas of 800. There were several family wars, the last of which was led by Irene against Constantine 4 -- she didn't want to give up the throne. Her forces captured, Constantine and blinded him with red-hot pokers (to make him ineligible -- an old Byzantine rule), but they drove the pokers in too far and he quickly died. Irene kept the throne, but her brutality cost her the marital alliance with Charlemagne. [For more info on the mid-Isaurian dynastic horrors go to http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constantine_VI and http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_Emperor_Irene.]

[This was the same Irene who suppressed the Iconoclasts.]

The Carolingian achievement was great, but Charlemagne had not eliminated the basic limitations inherent in the Frankish state. The economic infrastructure of the West had not been repaired, and the reconstruction of anything remotely resembling a Western Roman empire was beyond the means of Charlemagne and his advisors. The Franks had gotten as far as they had simply because their rivals were engaged elsewhere, and they had the good fortune to have enjoyed almost seventy years in which the kingdom had passed to a single heir and so remained united and free from civil wars According to legend, the pope put the crown on Charlemagne's head spontaneously, but, even then, nobody believed that long planning and negotiations had not preceded the event. It's just barely possible, however, that the Pope figured out "which side of the bread the butter was on" and took action without consulting Charlemagne. Whatever was the case, Charlemagne was clearly pleased -- not quite realizing, perhaps, that the act of king-making is more empowering to the maker than to the king.

The coronation ended Byzantine theoretical rule over the West, and successive Western Rulers -- ultimately the Holy Roman Emperors and even modern Western Monarchs could claim continuity with the emperors of ancient Rome. (They already could prove distant consanguinity -- very distant.)

This good fortune came to an end in the reign of Charlemagne's son, Louis (AKA, Clovis/Chlodoweg/Ludvig) the Pious, who squandered most of his Father's gains.

More info

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/einhard.html

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11662b.htm

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03610c.htm

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03629a.htm

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/lect/med09.html

http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Frankish_Kings

http://pirate.shu.edu/~wisterro/cdi/0756a_donation_of_pepin.htm

[Note 1. During his lifetime, Charlemagne and his advisors managed a minor "renaissance" (called, unsurprisingly, the Carolingian Renaissance) in which they attempted to re-create the Roman Empire of the West as best they could. The primary goal of this effort was to concentrate authority permanently in a central government, and, from the beginning, that goal was probably unattainable. They failed to address the basic problems of the West: the decay of the economic infrastructure (roads, bridges) and the loss of the manufacturing and monetary subsidy that the West had obtained from the East as long as both were under the control of a single imperial authority, and being unable to address these problems, they were not able to command the respect needed for long term central contol.

More importantly, they failed to address the problem caused by the division of the state among the king's heirs according to the traditional inheritance practice of gavelkind. It was only luck that had kept the Frankish realm in the hands of a single ruler from 751 to about 830.]

[Note 2. Something about Louis the Pious:

Louis was born in 778, while Charlemagne was on an expedition to Spain. Charlemagne gave him the newly-acquired land of what is now southern France, stretching from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, with its capital at Toulouse, and with the name of the Kingdom of Aquitaine. He left the child there under the care of a very able group of secular and clerical counsellors led by Count William of Toulouse (William of Orange in the epics, and St. William of the Desert in the lives of the saints) and Saint Benedict of Aniane, monastic reformer, scholar, and political theorist. Louis had older brothers, so he did not expect ever to get more of his father's lands than the kingdom he had been given. But when Charlemagne died in 814, his brothers were already dead: Louis inherited everything. Gavelkind was avoided.]

Louis, Charlemagne's sole heir, started out smart. By deposing all illegitimately born men from the civil service and the Church hierarchy, he took away the ability of Charlemagne's many bastards to grant political favors (but he also made a bunch of enemies and took out some experienced administrators.)

In Italy there was a short-lived rebellion centered around a child pretender (said to be one of Charlemagne's bastards) named Bernard. Louis put it down, with wide Italian public support, but his torturers botched their job of blinding the child, and the boy's death was a public relations disaster -- Louis should have read what the family chronicles said about Irene.

At that point, the Church exercised the "empowerment" that it had gained when Pope Leo crowned Charlemagne: there would be no coronation for Louis until he did "penance", and he had to do it, literally had humble himself in front of his court. This clearly would have troubled some of Charlemagne's powerful nobles.

Louis made another mistake when he tried to update his early attempt to ensure an orderly succession. To avoid disputes caused by Gavelkind at his death, he had distributed the various parts of the realm to his three sons while he was still alive: there would be no question of "inheritance". The plan went askew when Louis, a widower, remarried and had another son. Louis announced that he was going to redraw the borders of the lands settled on the first three sons to give his new son an equal share. The first three objected and there was civil war -- which lasted for generations.

A new problem emerged because it was no longer possible to expand the "empire". Infighting essentially prevented "outfighting", and that meant that benefices and, more importantly, tax-farming rights were no longer available to pacify the nobles. That meant they had to look more to their internal fiefs for income -- and, in turn, it meant a decentralization of power.

Louis died in 840 and his first three sons divided the realm among themselves. By 843 the Treaty of Verdun was hammered out (but there was still violent jostling and civil war along the borders of the three divisions). The jostling created new realities, and by 870 a new Treaty of Mersen was signed. Three divisions, West Franks, East Franks and Middle Franks resulted. The west Franks eventually became France. The East Franks became the Holy Roman Empire, which absorbed and for a long time kept "Lotharingia", the lands of the Middle Franks. Lotharingia, as we can see from the maps, included the northern half of Italy and, more specifically, all that territory around Rome that was included in the Donation of Pepin. [One of the eventual results of decentralization was the inability to agree on maintaining a navy to defend against piratical Saracens. And at about the same time, there were new "barbarians", fierce Magyar horsemen on the borders. If all this sounds familiar, it's because it was the same scenario that played out at the end of the ancient Roman Empire, but things moved faster in modern times -- it only took a few generations.]

Transition from Carolingian to Holy Roman After the Donation of Pepin and subsequent Carolingian events the church became much more wealthy as a result of the increase in the size of Papal estates. There was once again surplus income building and aggrandizing churches. The city of Rome was one of the places where this occurred. We are still in the Romanesque period before the rise of European Gothic architecture (which never really caught on in Rome anyway. In Rome, only the 12th century church of S. Maria Sopra Minerva is Gothic, and its nave is nowhere near as high as in Gothic churches elsewhere, and its interior was repainted/redecorated in the 19th century in a thoroughly "un-Gothic" style.) A chart of all the Merovingians and Carolingians is at http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Frankish_Kings

Two notable examples of Carolingian era churches in Rome are Santa Cecilia in Trastevere and Santa Prassede. There were pre-existing churches on both sites, but what we see today are the Carolingian rebuilds. Each has a formidable collection of important and well-preserved mosaics from the Carolingian period (better preserved, in fact, than the later Late Medieval and Renaissance frescoes which are considered equally important in art history.) Guelphs and Ghibellines The tripartite division among the Grandsons of Charlemagne and their heirs was largely linguistic -- "French" speakers were in the west, and "German" speakers in the East. All of the Franks, of course, were "Germanic", but the West Franks were in old Gaul, where centuries of Roman domination had "Latinized" both the street and the Palace. Middle Frankish Lotharingia had a mixed "French" and "German" area in the north and an "Italian" speaking area in the south -- all those quotation marks, by the way, indicate developing rather than fully grown languages.

Between the Treaty of Verdun (843) and the Treaty of Mersen (870) the Eastern and Western Franks divided the northern part of Lotharingia between themselves. Neither side was happy with the division, and both sides coveted the southern, "Italian", part of Lotharingia. Disputes and wars involving the northern part would be the cause of bitter territorial disputes between France and Germany until the first half of the 20th century.

In the ninth and tenth centuries, Europe was disrupted by a series of invasions by Vikings, Hungarians, and Muslims.

When the invasions finally subsided, Germany's initial recovery was characterized by the emergence of semi-independent duchies based on earlier Germanic tribal divisions, and by the early tenth century, five duchies dominated Germany: Bavaria, Franconia, Lorraine, Saxony, and Swabia.

After the death of the last Carolingian emperor in 911, the monarchy fell into the hands of the dukes of Franconia and Saxony until the Saxon line was able to assimilate the crown into their dynastic line. The dukes of Saxony soon extended their control over Franconia and Lorraine and retained the German monarchy for the next century.

The second king in the Saxon line was Otto I, the Great, who consolidated his authority in Germany and then added the title of 'King of Italy' in 951. His successful defense of Germany against the Hungarians in 955 validated his claim as monarch over the German princes and, in 962, Otto I was crowned 'Roman Emperor' by Pope John 12.

Although the term 'Holy Roman Empire' would not be regularly used until the twelfth century, for later historians the coronation Otto 1 marked the beginning of the medieval Holy Roman Empire which was to remain a fundamentally German phenomenon until its demise in the nineteenth century (and successor regimes continue until today).

We won't follow the complex line of Holy Roman history, but will now shift southward to Italy.

[A basic outline/timeline of Holy Roman Empire history is available at

http://www.scaruffi.com/politics/holy.html and there are libraries full of books for those who really want to dig in.]

It should be noted, before we shift into Italy, that, at various times, and in some circumstances, the "Holy Romans" have claimed that the Holy Roman Empire started with Charlemagne or even with his ancestors.

Roman Guelphs and Ghibellines [First, another German digression: Italian Guelphs and Ghibelline How the Names Originated: Welf vs. Waiblingen They originated in the 12th century from the names of rival German houses in their struggle for the title of Holy Roman Emperor. The election, favored by the Pope, of Lothair II (c. 10701137), Holy Roman emperor from 1133 and German king from 1125, was opposed by the Hohenstaufen family of princes.

This was the start of the feud between the house of Welf (Guelph), the followers of the dukes of Saxony and Bavaria (Henry the Proud, 11081139; later of his son Henry the Lion, 11291195), and that of the lords of Hohenstaufen whose castle at Waiblingen (near present-day Stuttgart) gave the Ghibellines their name.

Eventually the Guelph-Ghibelline conflict gave way to a civil war in Germany, which was finally settled in 1152 by the election of Frederick I (Barbarossa), the son of a Hohenstaufen father and a Welf mother.

When Henry the Lion (Welf) incurred the disfavor of the Holy Roman emperor Frederick Barbarossa in 1180, Waiblingen and his lands were forfeited to a duke of the Wittelsbach family a dynasty that was to dominate Bavarian history until the end of World War I.

The Guelph-Ghibelline feud continued for another two centuries, but it became a specifically Italian conflict between forces opposed to the papacy and those supporting it.]

In Italy, the terms Guelfi and Ghibellini were introduced about 1242 in Florence. The names seem to have been grafted on to pre-existing papal and imperial factions within the city-republics. Eventually the original "party platforms" became obfuscated by mere struggles for power by local factions so that if a rival city became Guelph, the other automatically became Ghibelline to maintain its independence.

The Italian Guelphs early became associated with the papacy because of their mutual Hohenstaufen enemy. They were represented by the more democratic 'middle classes' and 'merchant class' who desired a constitutional government. They represented an indigenous Italian stock and looked to the Pope for help against the Ghibellines. However this distinction became more and more blurred as we shall see in Dante's case. Aribert (died 1045), Archbishop of Milan 101845, should have been a Guelph on the side of the Pope; instead he was one of the early leaders of the Ghibelline party. In fact 1026 he crowned the emperor Conrad II as king of Milan. The Colonna family in Rome, an old and illustrious Italian family that produced popes, and cardinals, belonged to the Ghibelline party.

Italian Ghibellines were aristocratic, contemptuous of the church, and supported the emperor. The Lombard League, an association of northern Italian towns and cities (not all of which were in Lombardy, nor were they all Lombards), was established 1164 to maintain their independence against the Holy Roman emperors' claims of sovereignty. Venice, Padua, Brescia, Milan, and Mantua were among the founders. Supported by Milan and Pope Alexander III (11051181), the league defeated Frederick Barbarossa at Legnano in northern Italy 1179 and effectively resisted Otto IV (11751218) and Frederick II. The League became the most powerful champion of the Guelph cause. Internal rivalries led to its dissolution 1250. Brunetto Latini (c. 12201294) was an Italian man of letters and public affairs. He was attached to the Guelph party and held some of the most important offices in the republic. His most noted work is an encyclopaedia, Li Livres dou trιsor, written in French. He was also the author of a didactic and allegorical poem, Il tesoretto; a moral epistle, Il favolello; and a treatise on rhetoric.

Dante was a Florentine Guelph politician in addition to being the great author ot the Divine Comedy, and eventually, when the Florentine region Guelphs split into "Black" and "White" factions, Dante was a White Guelph and was persecuted when the Blacks won control.

Ezzelino da Romano (died 1259), was a leader of the Ghibelline movement. His reputation for cruelty led to him being called 'the tyrant' and he was depicted as a tyrant in Dante's Inferno. Guido Cavalcanti (c. 12551300) was arguably the greatest Italian poet before Dante. He was a friend of Dante and a leading exponent of the dolce stil nuovo ["sweet new style", how Dante used the language -- tkw]. Cavalcanti married Beatrice, daughter of Farinata degli Uberti, head of the Ghibelline faction in Florence (Inferno VI, v. 79 and X, v. 22). When the leaders of both Guelphs and Ghibellines were driven out by the rulers of Florence, he was banished to Sarzana and returned to Florence only to die.

Guido Guinizelli (c. 12301276) was another Ghibelline of the Lambertazzi party from Bologna. He was exiled in 1274 and died never to return to his native Bologna.

In Florence, the Ghibellines, with the help of Frederick II (grandson of Frederick Barbarossa) won the first round and banished the Guelphs from the city (1249). When Frederick II died in 1250, the Guelphs came to power again for 10 years. During this period Florence flourished both economically and politically. However, the fateful battle of Montaperti (1260), in which the Florentines lost to the Sienese, was to obliterate all that the merchant middle class (Guelphs) had accomplished politically. With the Guelphs responsible for the loss, the Ghibellines resumed power, restored the old institutions, and decreed the destruction of the palaces and towers and houses which the principal exponents of the Guelph party owned in the city and in the surroundings. All of Tuscany was in the hands of the Ghibellines except Lucca. For six years Florence was forced to submit to these outrages. At the Ghibelline League convention of Empoli, it was resolved that Florence itself be razed to the ground. It would have been destroyed had it not been for the fearless defense of Farinata degli Uberti who spoke vehemently in opposition saying that he would defend his native city with his own sword.

Petrarch was a Roman Ghibelline.

Shakespearian Guelphs and Ghibellines Medieval Roman noble families chose Guelph and Ghibeline banners, but mostly as a way of advancing family fame and fortune and Papal aspirations. As noted above, the Colonna were Ghibelline and their great rivals, the Orsini, were Guelph. As their sometimes violent rivalry progressed each family had its peaks and valleys and each produced great statesmen and scoundrels -- the only difference being who was in power.

Eventually, other families, often from outside the city, later also joined the Papal/Imperial fray -- the Spanish Borgias and the Florentine Medici are the first to spring to mind. Family names eventually became more important than "Guelph" or "Ghibelline" as factional identifiers as control of the Papacy shifted among families-- and here we're moving out of Medieval and into Renaissance.

There's more on this available in a chapter of Jacob Burkhardt's famous book, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. The whole book is available on the Internet at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2074.

More info Elizabethan England was fascinated with Italy. There were several famous Italian exiles in the English court -- they had fled to Protestant England to escape church persecution (or in some cases, apparently, to capitalize on "exile" notoriety). Elizabethan drama was full of "Italian" stories derived from prose and poetry in mass printed circulation. The most popular were those that featured "uncivilized" Italian violence -- supposedly in contrast to (Protestant) England's law and order. (It actually got even worse after Shakespeare -- the last "Elizabethan" dramatist, John Webster, was disgustingly violent. Full text of his Duchess of Malfi is on the Internet at http://larryavisbrown.homestead.com/files/Malfi/malfi_home.htm .)

There has always been speculation about whether Shakespeare traveled in Italy. Some modern Shakespeare scholars maintain that his "Italian" works could only have attained their coherence if the Bard had experienced Italy first hand, but others say, with some justification, that he merely lifted entire stories from works by Italian authors -- stories that already had been translated and published in England.

Two of Shakespeare's plays have direct "Guelph and Ghibelline" story lines. The Montagues and Capulets of Romeo and Juliet were based on two influential families in Venetian society -- the Montecchis (Ghibellines) and the Capuleti (Guelphs). The willingness of the bravos in each family to provoke each other into street fights is understandable in the context of Guelph-Ghibelline feuding. At the time Romeo and Juliet was written, the prevalence of street swordplay in Italy -- usually associated with Guelph-Ghibelline conflict -- was a topic of scandalized conversation in England.

And in Twelfth Night, Orsino, Duke of Illyria, is easy to identify as one of the Orsini, and the pre-play situation that led Viola to disguise herself was family enmity -- she and her brother Sebastian can be Colonnas, or at least, Colonna allies. Sebastian's friend, Antonio, is in hiding because he, as a sea captain, has fought against the Orsini.

Elizabethan plays were written to be enjoyed by the unlettered mass of groundlings (the cheap standing-room crowd whose place was on the ground in front of the stage) as well as by the literate and history-aware upper classes in the upper tiers of the Rose and Curtain theaters, and, later, the Globe. Although the groundlings would not be expected to catch Shakespeare's references to the Italian feud, the upper classes probably would have understood the context and may even have read one of the earlier versions of the story.

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07056c.htm